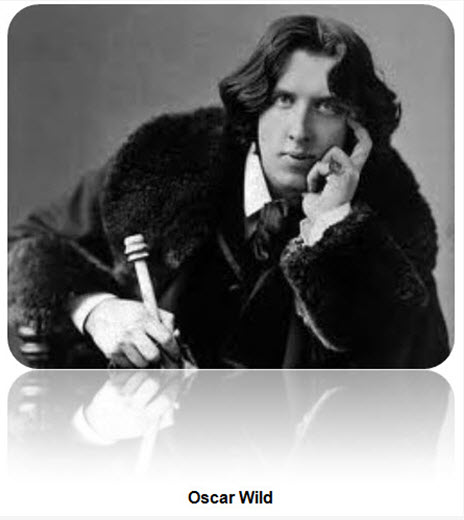

Today we republish the well-known story of Oscar Wilde who died in 1900 after a sentence of two years in jail for sexual offences. His case should never have come to Court and certainly it should never have been permitted by the Trial Judge for reasons that are evident.

John Sholto Douglas, the Marquis of Queensberry was an arrogant, ill-tempered, eccentric and perhaps even mentally imbalanced Scottish nobleman best noted for developing and promoting rules for amateur boxing (the ‘Queensberry rules’). Queensberry became concerned about his son’s relationship with ‘this man Wilde’. His concern was temporarily alleviated at the Cafe Royal in late 1892, when his son introduced him to the noted literary figure. Wilde charmed Queensberry over a long lunch with many cigars and liqueurs. By early 1894 Queensberry concluded the Wilde was most likely a homosexual and began demanding that his son stop seeing Wilde: ‘Your intimacy with this man Wilde must either cease or I will disown you and stop all money supplies,’ Queensberry wrote in April. ‘I am not going to try and analyse this intimacy, and I make no charge; but to my mind to pose as a thing is as bad as to be it.’ Douglas replied in a telegram: ‘What a funny little man you are.’

Queensberry began taking increasingly desperate measures to end the relationship. He threatened restaurant and hotel managers with beatings if he ever discovered Wilde and his son together on their premises. In June of 1894 Queenberry, accompanied by a prize-fighter, showed up without warning at Wilde’s house in Chelsea. An angry conversation ensued, ending when Wilde ordered Queensberry to leave saying, ‘I do not know what the Queensberry rules are, but the Oscar Wilde rule is to shoot on sight.’

Queensberry’s subsequent letters to his son, who he had already ceased to support, grew increasingly intemperate. ‘You reptile,’ he wrote, ‘you are no son of mine and I never thought you were.’ Douglas answered, ‘If O. W. was to prosecute you in the criminal courts for libel, you would get seven years’ penal servitude for your outrageous libels.’

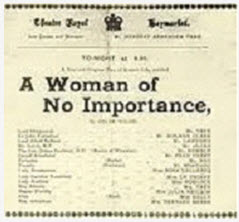

On February 14, 1895, Wilde’s new play ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’ was set to open at the St. James Theatre. Wilde learned that Queensberry planned to disrupt the opening night’s performance and harangue the audience about Wilde’s alleged decadent lifestyle. Wilde arranged to have the theatre surrounded by police. His plan blocked, Queenberry prowled about outside for three hours before finally leaving ‘chattering.’

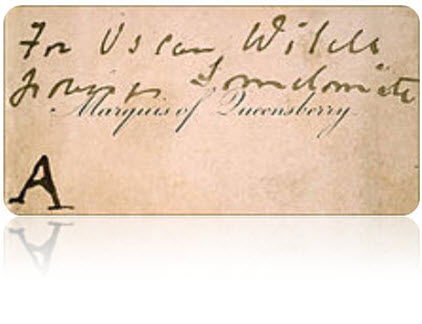

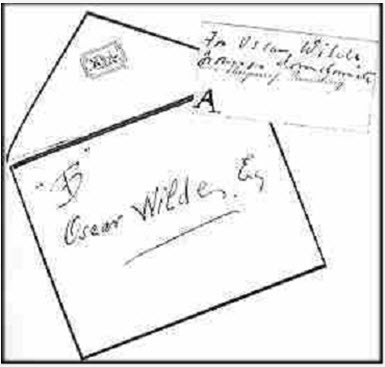

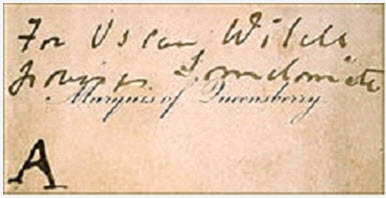

Four days later at the Albemarle Club–a club to which both Wilde and his wife belonged, Queensberry left a card with a porter. ‘Give that to Oscar Wilde,’ he told the porter. On the card he had written: ‘To Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite [sic].’ Two weeks later Wilde showed up at the club and was handed the card with the offensive message. Returning that night to the Hotel Avondale, Wilde wrote to Douglas asking that he come and see him. ‘I don’t see anything now but a criminal prosecution,’ Wilde wrote. ‘My whole life seems ruined by this man. The tower of ivory is assailed by the foul thing. On the sand is my life split. I don’t know what to do.’

The next day, Wilde, Douglas, and another long-time friend named Robert Ross visited a solicitor, Travers Humphreys. Humphreys asked Wilde directly whether there was any truth to Queensberry’s allegation. Wilde said no. Humphreys applied for a warrant for Queensberry’s arrest. On March 2, Queensberry police arrested Queensberry and charged him with libel at the Vine Street police station.

The Marquis of Queensberry was charged under the Libel Act 1843 s.4 which stated as follows:

‘If any person shall maliciously publish any defamatory libel,

knowing the same to be false, every such person, being convicted

thereof, shall be liable to be imprisoned in the common gaol or

house of correction for any term not exceeding two years, and to

pay such fine as the court shall award.‘

This section did not create or define an offence. It provided the penalty for the existing common law offence of defamatory libel. This was abolished in England and Wales only in 2010.

The Libel Act 1843 s.6 allowed the defendant to prove the truth of a libel as a valid defence in criminal proceedings, but only if it also be demonstrated that publication of the libel was to the ‘Public Benefit.’

Proving the statement’s truth had previously been allowed only in civil libel defences inasmuch as the criminal offence against the public at large was considered to be provoking a breach of the peace via printing malicious statements rather than the defamation per se; the truth or falsity of the statement had therefore been considered irrelevant in criminal proceedings before the Act.

The Libel Act 1843 s.6 was expanded well before the Trial of the Marquis of Queensberry to read in full as follows:

‘Proceedings upon the trial of an indictment or information for a defamatory libel. Double plea. Proviso as to plea of not guilty in civil and criminal proceedings. On the trial of any indictment or information for a defamatory libel, the defendant having pleaded such plea as hereinafter mentioned, the truth of the matters charged may be inquired into, but shall not amount to a defence, unless it was for the public benefit that the said matters charged should be published; and to entitle the defendant to give evidence of the truth of such matters charged as a defence to such indictment or information it shall be necessary for the defendant, in pleading to the said indictment or information, to allege the truth of the said matters charged in the manner now required in pleading a justification to an action for defamation, and further to allege that it was for the public benefit that the said matters charged should be published, and the particular fact or facts by reason whereof it was for the public benefit that the said matters charged should be published, to which plea the prosecutor shall be at liberty to reply generally, denying the whole thereof; and if after such plea the defendant shall be convicted on such indictment or information it shall be competent to the court, in pronouncing sentence, to consider whether the guilt of the defendant is aggravated or mitigated by the said plea, and by the evidence given to prove or to disprove the same: Provided always, that the truth of the matters charged in the alleged libel complained of by such indictment or information shall in no case be inquired into without such plea of justification: Provided also, that in addition to such plea it shall be competent to the defendant to plead a plea of not guilty: Provided also, that nothing in this Act contained shall take away or prejudice any defence under the plea of not guilty which it is now competent to the defendant to make under such plea to any action or indictment or information for defamatory words or libel.’

In this instance it is important to understand fully the wording of the ‘publication’ which from the archives of the trial is as below:

Today we republish the well-known story of Oscar Wilde who died in 1900 after a sentence of two years in jail for sexual offences. His case should never have come to Court and certainly it should never have been permitted by the Trial Judge for reasons that are evident.

The actual wording used by the Marquis of Queensberry was ‘To Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite [sic].’ The word used is not ‘sodomite’ but ‘somdomite.’

On the 3rd April 1895 however, Sir Edward Clarke for Oscar Wilde opened the case as follows:

John Sholto Douglas, Marquis of Queensberry, pleaded not guilty, and also that the libel was true and that it was for the public benefit that it should be published.

Sir Edward Clarke-‘May it please you my lord, gentlemen of the jury. You have heard the charge against the defendant, which is that he published a false and malicious libel in regard to Mr. Oscar Wilde. That libel was published in the form of a card left by Lord Queensberry at a club to which Mr. Oscar Wilde belonged. It was a visiting card of Lord Queensberry’s, with his name printed upon it, and it had written upon it certain words which formed the libel complained of. On that card his lordship wrote: ‘Oscar Wilde posing as a sodomite.’ Of course it is a matter, of serious moment that such a libel as that which Lord Queensberry wrote upon that card should in any way be connected with a gentleman who has borne a high reputation in this country. The words of the libel are not directly an accusation of the gravest of all offences the suggestion is that there was no guilt of the actual offence, but that in some way or other the person of whom those words were written did appear-nay, desired to appear-and pose to be a person guilty of or inclined to the commission of the gravest of all offences. You will appreciate that the leaving of such a card openly with the porter of a dub is a most serious matter and one likely gravely to affect the position of the person as to whom that injurious suggestion was made.’

In all his eloquence and esteem Sir Edward Clarke erred. The case should properly have been stopped there and then by the Trial Judge upon examination of the actual publication. If one considers carefully the Libel Act 1843 s.6 in its entirety namely the section that permits a defence the words used by the legislators are ‘the truth of the matters charged may be inquired into, but shall not amount to a defence.’

There is no such word in the English dictionary as ‘somdomite’ and as such neither could such a word be deemed or covered by the Libel Act 1843 since a non-existent word or phrase cannot de jure be deemed Libel and as a consequence nor could any defence be presented compliant to The Libel Act s.6 since no offence was committed.

Sir Edward Clarke erred and as the exhibits were presented in Court and available the Trial Judge should have at that stage, or prior to such, intervened. The Libel Act 1843 was a penal statute and as such had to be strictly interpreted. The word ‘somdomite’ which was the actual de facto and de jure word used which deemed a libel was erroneously referred to by Sir Edward Clarke as ‘sodomite’ which of course would have been subject to criminal libel.

The trial Judge Mr Justice Collins ought properly to have intervened at that stage. His failure in doing so and permitting an error to be continued prejudiced (a) the outcome of the trail and (b) was the cause of criminal proceedings to be launched against Wilde.

Defence Counsel Edward Carson at no stage in his speech on April 4th and 5th 1895 did he seek to comply with the ‘public interest’ element which was a pre-requisite under The Libel Act 1843 s.6 but more important failed wholly to deal with the actual published criminal libel the word ‘somdomite’ instead concentrating on the word ‘posing.’ In his closing speech Carson confirms this approach by saying:Sir Edward Clarke on the 5th April 1845 concedes the verdict of ‘not guilty’ against the Marquis of Queensberry solely on the basis of the word ‘posing’:

‘Lord Queensberry has undertaken to prove that Mr. Wilde has been ‘posing’ as guilty of certain vices.’

Sir Edward Clarke on the 5th April 1845 concedes the verdict of ‘not guilty’ against the Marquis of Queensberry solely on the basis of the word ‘posing’:

‘Under these circumstances I hope your lordship will think I am taking the right course, which I take after communicating with Mr. Oscar Wilde. That is to say that, having regard to what has been referred to by my learned friend in respect of the matters connected with the literature and the letters, I feel we could not resist a verdict of not guilty in this case–not guilty having reference to the word ‘posing.’ Under these circumstances I hope you will think I am not going beyond–the bounds of my duty, and that I am doing something to save, to prevent, what would be a most horrible task, however it might close, if I now interpose and say on behalf of Mr. Oscar Wilde that I would ask to withdraw from the prosecution.’

However, the offence of ‘posing as a somdomite’ which was the published libel and the charge was altered, without leave of the Court, by error. The error on the part of Sir Edward Clarke, the error of Mr Justice Collins and the error of Sir Edward Carson all noted eminent and more than qualified practitioners.

As a consequence Wilde was subsequently prosecuted, wrongly since had the trial against the Marquis of Queensberry been stopped as it should have been since ‘somdomite’ is a non-existent word and The Libel Act 1843 did not carry defamation by innuendo as the subsequent Defamation Acts would in the next century, and jailed.

Oscar Wilde ought properly be pardoned not only for de jure motives but because today the acts that he was accused of, and convicted, under the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 s.11 are certainly unthinkable but homosexuality is tolerated, permitted and promoted.

Under the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 s.11 – that cost Wilde two years in Reading jail- there was no definition given of what, exactly, constituted ‘gross indecency,’ as Victorian morality demurred from giving precise descriptions of activity considered immoral. In practice, ‘gross indecency’ was widely interpreted as any male homosexual behaviour short of actual sodomy which remained a more serious and separate crime.

Yet it was ‘sodomy’ that was the basis of the criminal prosecution of Queensberry under the Libel Act 1843 s.4

We have written to the Home Secretary to recommend to HM Queen Elizabeth to apply the prerogative of pardon posthumously for Oscar Wilde in the public interest.

For the posthumous pardon of Oscar Wilde email your support to: contactopcglobal@gmail.com

The Life And Trials Of Oscar Wilde

In literature, the pursuit of forbidden love often has tragic consequences. For Oscar Wilde, a prolific literary genius and social critic who was at the peak of his success in the late 19th century, those consequences were all too real. His fall from grace, like that of a classic tragic hero, was swift and complete.

In many ways Wilde was ahead of his time. As an aesthete – one who believed that art must be judged only as art and not by contemporary morality, he had forward-thinking views on censorship and obscenity; he refused to acknowledge that books could be moral or immoral. To him a book was either well written or poorly written. Well-written pornography was preferable to bad literature, regardless of the social merit of either. Wilde was also egotistical. He embraced the idea that his genius placed him above the law and subject to different rules of morality.

Book cover: The Picture of Dorian Gray

Book cover: The Picture of Dorian Gray

Oscar Wilde was also a homosexual in a time when being gay was a criminal offense. As a cover, Wilde was married with two children and an extraordinarily beautiful and loyal wife, and was for the most part discrete in his homosexual activities. His most popular work, The Picture of Dorian Gray, had caused a stir because of its not-so-subtle homosexual references, but Wilde did not write Dorian Gray as a protest piece. The homosexual element of Dorian Gray was more of a literary device, a gay version of medieval courtly behaviour, when a knight pledged his love for an unobtainable lady in platonic form.

His flamboyant lifestyle, ego and choice of romantic partners had dire consequences. Wilde was persecuted for his art and for his love of another man. In some ways, his pride and poor judgment in matters unrelated to art would cost him everything.

Oscar and Bosie

A young Lord Alfred Douglas

Oscar and Bosie, as his friends called Lord Alfred Douglas, met in Chelsea when Bosie was 22 and Wilde 15 years his elder. Oscar immediately became enamoured with Bosie, who was thrilled that such a literary genius was interested in him.

Bosie referred to Wilde as “the most chivalrous friend in the world” and was willing to forsake his birth-right for the friendship. They exchanged letters, with some of Wilde’s containing what could be interpreted as expressions of passionate love.

‘It is a marvel that those red-rose leaf lips of yours should be made no less for the madness of music and song than for the madness of kissing,’ Wilde wrote to Lord Alfred in 1893. ‘Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry.’

Bosie was flagrantly and openly homosexual, a spendthrift and gambler, according to Wilde’s biographer, Richard Ellman. He was a dropout at Oxford, a ne’er-do-well who was as loose with his morals as he was with his purse. He had his family’s temper, which flared when he didn’t get his way.

‘Bosie’ chalk and pastel drawing by Sir William Rothenstein Oxford, 1893

Bosie knew of Wilde’s affection for him early on and succeeded in using it to his advantage. He relied on Wilde’s money when his own ran out and would pout and threaten self-injury when Wilde complained of his behaviour or criticised his literary skills. For the length of their relationship, Lord Alfred used Oscar’s love for him as a means to get what he wanted. In the end, Wilde sacrificed himself to protect Lord Alfred, who remained a loyal, yet manipulative, friend.

For Wilde, who was much more low-key about his sexuality, it was a love-hate relationship, almost akin to the moth and flame. He lusted for Lord Alfred, but knew that Bosie would only hurt him. His head told him the cost of Bosie’s love was too expensive, his heart considered it a bargain.

‘Wilde wanted a consuming passion,’ Ellman wrote. ‘He got it and was consumed by it.’

‘Gross Indecencies’

Homosexuality had been illegal in Britain for hundreds of years and prosecuted to varying degrees by different monarchs. From the 16th century to the early 1800s, homosexuality was a capital crime, though the crime was rarely punished so severely. Beginning in the 1830s, imprisonment was the penalty for practicing sodomy, defined as any kind of non-reproductive sexual contact, regardless of gender.

A sexual morality and social improvement movement in the 1880s resulted in strong legislation against pedophilia, as well as sodomy. The Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885 raised the age of consent from 13 to 16 and section 11 of the act made “gross indecencies” punishable by imprisonment as a misdemeanor. Prior to the Criminal Law Amendment Act a sexual assault against a child between 13 and 16 was not a criminal offence, and Parliament had intended section 11 to apply only to pedophilia cases. Instead, conservative judges began to consider homosexual sodomy cases under the gross indecencies clause. (No lesbians were ever prosecuted because when she approved the act, Queen Victoria was said to be flabbergasted at the idea of Sapphic love.) Prosecution was still rare, however, and pursued only in the most indiscreet cases. Wilde, on the other hand, was not a man to be discrete in any activity.

Oscar Wilde & Lord Alfred Douglas, 1893 (Library of Congress)

In 1894 Lord Alfred published a poem, “Two Loves,” in the controversial British literary magazine The Chameleon, which also featured works by Wilde. The romantic poem, probably Bosie’s best effort, ends:

What is thy name?’ He said, ‘My name is Love.’

Then straight the first did turn himself to me

And cried, ‘He lieth, for his name is Shame,

But I am Love, and I was wont to be

Alone in this fair garden, till he came

Unasked by night; I am true Love, I fill

The hearts of boy and girl with mutual flame.’

Then sighing, said the other, ‘Have thy will,

I am the love that dare not speak its name.’

The poem was published at about the same time The Picture of Dorian Gray was making waves in the literary world. Lord Alfred’s poem, considered a paean to homosexuality, caused quite a stir in England, especially in the home of the Marquis of Queensberry.

Queensberry Rules

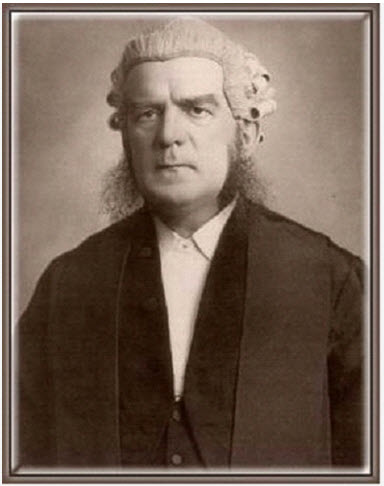

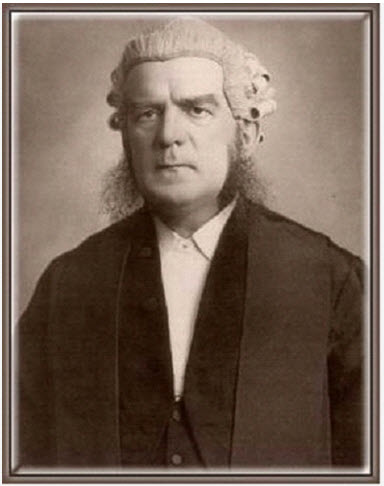

Marquis of Queensberry

Marquis of Queensberry

Lord Alfred Douglas was the son of the Marquis of Queensberry, a hot-headed Scotsman, who was prone to violence. It could have been because he was punch drunk; Queensberry was a champion pugilist and created rules of boxing still in use today. He tended to settle things by fist and gun. He was well known for abusing his wife and children and had even brawled openly with one son in downtown London.

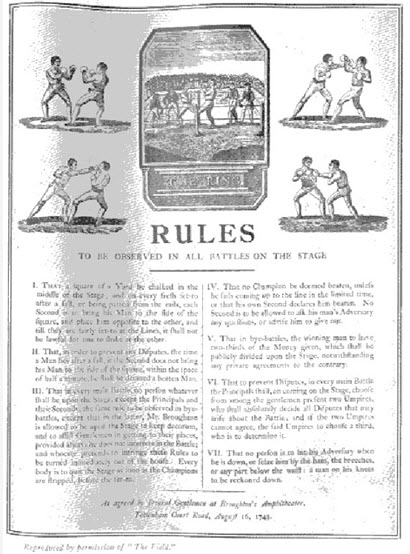

Marquis of Queensberry’s boxing rules

The Marquis was an avowed and belligerent atheist who saw nothing wrong with disrupting services by shouting. Once he disrupted the premiere of a play that he felt too pious and in front of the Prince of Wales attempted to whip a cabinet minister because he feared the man was courting his oldest son.

Queensberry seemed obsessed with sex, perhaps because his second wife had sought an annulment soon after marriage because of ‘malformation of the parts of generation, frigidity and impotence.’ His first marriage had ended because of his adultery.

The Marquis had difficulty getting along with his son. The Marquis could barely stand to be in the same room with Lord Alfred and the feeling was mutual. Everything Queensberry was, Lord Alfred was not. Lord Alfred was a poet and dreamer. He was handsome, frail and fair, where Queensberry was windblown, tough and leathery. The Marquis was a fighter and Lord Alfred was a philosopher.

Queensberry loathed Lord Alfred’s way of life and let him know it in no uncertain terms. Lord Alfred once replied to one of the Marquis’s rantings with, ‘What a funny little man you are.’

In normal circumstances, the Marquis and his son would merely avoid each other, and they traveled in different circles. Upper class London was small, but not so small that one could not live a full life without encountering the other.

Queensberry suspected Wilde was a homosexual and was bent on seducing Lord Alfred. The publication of ‘Two Loves’ proved it to him.

The Marquis tried everything he could to pull his son from Wilde’s clutches. He stalked the men as they went about London and accosted any restaurateur who served them. He threatened his son with excommunication from the family. Still Lord Alfred and Oscar remained close friends.

“Your intimacy with this man Wilde must either cease or I will disown you and stop all money supplies,” Queensberry threatened in 1893. He publicly scolded his son and even showed up at Wilde’s house with a champion boxer to threaten the author. Wilde’s response was, “I do not know what the Queensberry rules are, but the Wilde rules are to shoot on sight!”

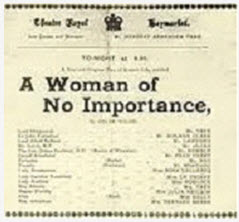

Book cover: The Importance of Being Earnest

The feud between Queensberry and Wilde went on for several years and came to climax as Wilde’s play The Importance of Being Earnest was set to premiere in London. Queensberry threatened to disrupt the premiere and ruin the performance. Given that he had previously successfully carried out a similar threat, Wilde took Queensberry seriously. He hired a cordon of guards to stand outside the theatre while the play was on. The Marquis tried to make good on his threat but was thwarted. He paced outside the theatre with a bouquet of vegetables until the performance was over.

Queensberry wrote once more to his son, following through on his threat to disown him. ‘You reptile, you are no son of mine and I never thought you were.

Lord Alfred answered, ‘If O.W. was to prosecute you in the criminal courts for libel, you would get seven years’ penal servitude for your outrageous libels.’

To Queensberry, a gauntlet had been thrown. If it took a libel trial to prove to the world that Oscar Wilde was a homosexual, so be it.

‘To Oscar Wilde’

Like a master chess player, Queensberry plotted his moves to destroy Oscar Wilde. And Wilde walked right into the trap.

It was a high time for Wilde. Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest were both critical and popular successes as was another play, The Ideal Husband. Master of the epigram and the bon mot, Wilde was the toast of London and a popular guest at parties. Seemingly uncaring that Queensberry was planning his downfall, he openly consorted with ‘renters’ young male prostitutes and held court in some of London’s finest establishments.

At the Albemarle Club where Wilde dined, Queensberry left his calling card complete with misspelling of the libelous word: ‘To Oscar Wilde, posing as a somdomite.’ Wilde felt he was left with no other choice but to defend his honour and sue for criminal libel. Queensberry had been stalking him, had threatened his livelihood, and now insulted him publicly.

Friends urged him not to sue, to shrug off the insult and move on, perhaps traveling to America or the continent. But Wilde would have none of it. He brought criminal charges against Queensberry and demanded satisfaction.

The Marquis expected no less and was prepared. In police court on Bow Street he made the statement ‘that not only had he called Wilde a sodomite, he had done so for the good of the general public.‘ This last statement was important, because now, if Wilde lost, the government would have no choice but to pursue criminal charges for gross indecency. To do otherwise would show favouritism for the elite.

Wilde expected the trial to be little more than a chance to exhibit his witty repartee on the stand. After all, it was up to Queensberry to prove the truth of his statements, not for Wilde to disprove them. The courtroom might have been a place of combat, but it was the type of combat that Wilde, not Queensberry, could exploit.

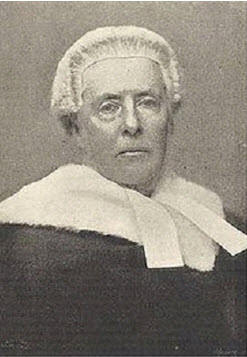

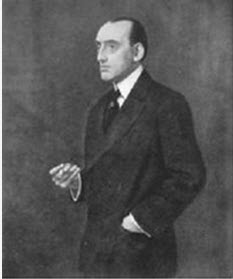

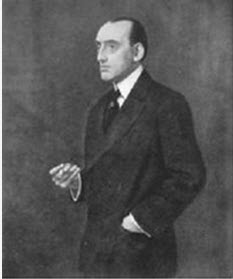

Sir Edward Clark, Wilde’s Barrister-in-law

Sir Edward Clark, Wilde’s Barrister-in-law

Wilde approached one of England’s most respectable barristers, Edward Clarke, and asked him to take the case for the prosecution. Clarke’s reputation was one of immense respectability and correctness. He did not often take cases in which he suspected his client was guilty and he demanded honesty from those he represented. His previous experience with sodomy cases was in the divorce court, where he represented jilted wives.

‘I can only take the case, sir,’ Clarke said, ‘if you assure me on your honour as an English gentleman that there is not and never has been any foundation for the charges that are made against you.’

Wilde very firmly said Queensberry’s charges were groundless and false and Clarke agreed to take the case.

The suit was doomed from the start, and Wilde’s closest friends knew it. The general feeling among those who cared in London was that Wilde was gay and that Queensberry’s allegations were true. It was also commonly believed that no jury would rule against Queensberry, for he could easily play the desperate father trying to save his son from Wilde.

But Lord Alfred was adamant that Wilde pursue the charges. His family, which believed the men when they said nothing untoward, was going on between them, agreed to pay for the trial, taking away Oscar’s last escape route.

The Libel Trial

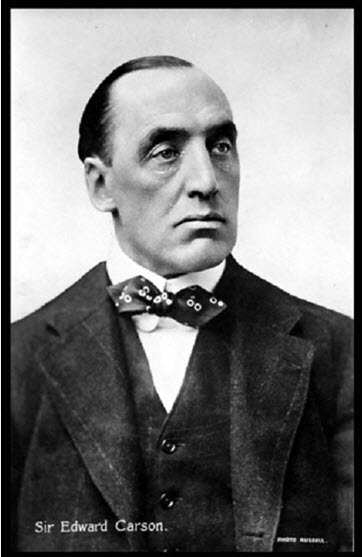

Edward Carson, Queensberry’s Barrister-in-law

Queensberry chose his defence counsel wisely. He engaged Edward Carson (later Sir Edward), who had attended Oxford with Wilde and had a competitive rivalry with Oscar there. A thin, balding man, Carson was soft-spoken but had the actor’s command of voice that allowed him to lull a witness into a false sense of security only to drill home a point with sonorous rumblings. He was a relentless questioner who could seize a weakness or contradictory statement and use it to destroy his adversary.

When Wilde learned whom he would face in court, he replied in typical Wildean fashion: ‘No doubt he will pursue his case with the added bitterness of an old friend.’

Returning from a holiday on the continent, Wilde was met by his family and friends, who urged him for the last time to drop the charges. They pointed out that if he should lose, the Crown would have no choice but to charge him with gross indecency under the Criminal Law Amendment Act.

‘Who are you to set back the clock 50 years?‘ asked his friend Frank Harris. ‘You haven’t a dog’s chance.’

But Bosie laid down an ultimatum. It’s them or me, he told Wilde, storming out of the meeting. Suddenly realizing the enormous stakes, Wilde could only shrug and say it was too late to go back.

On April 3, 1895, the trial opened in London. It was a celebrated affair, for the men involved were of highest English society and the testimony promised to be as entertaining as any of the fictions Wilde had written.

Sir Edward Clarke opened the trial. In journeyman style he laid out the history of the relationship among Wilde, Bosie and Queensberry. He sought to dull the shock of the flowery language in the letters Wilde wrote to Lord Alfred by introducing them himself, rather than giving Carson the advantage.

‘The words of that letter, gentlemen, may appear extravagant to those in the habit of writing commercial correspondence, or those ordinary letters which the necessities of life force upon one every day’ Clarke said. ‘But Mr. Wilde is a poet, and the letter is considered by him as a prose sonnet, and one of which he is in no way ashamed and is prepared to produce anywhere as the expression of true poetic feeling, and with no relation whatever to the hateful and repulsive suggestions put to it in the plea in this case.’

Opening Round

The preliminaries out of the way, Clarke called Oscar Wilde. Wilde carried himself regally to the witness stand, took the oath, and gave a brief introduction about himself to the jury.

Clarke, as skilled a barrister as ever set foot in Old Bailey, knew that it was better to have bad news out on direct examination rather than let Carson reveal it during cross-examination. He began asking the embarrassing questions. The first was about an incident of blackmail involving Oscar and Bosie.

Several years prior, while Lord Alfred was in school at Oxford, he gave a suit of clothes to a down-and-out friend, Alfred Wood. Unbeknownst to Lord Alfred, the letters from Wilde in which he wrote of Alfred’s ‘kissable lips’ were in the suit and were found by Wood.

Wood offered the letters back to Wilde for 30 pounds, which Wilde paid. Left unsaid in the testimony was a more physical relationship between Alfred Wood and Oscar Wilde.

Clarke then asked Wilde to tell of his relationship with Queensberry.

‘I pointed him out to my servant,’ Wilde said after recounting the episode in which Queensberry came to Oscar’s home uninvited. “I said, ‘this is the Marquis of Queensberry, the most infamous brute in London. You are never to allow him to enter my house again.’

Next, Clarke asked Wilde if he was a homosexual.

‘It is not true that I was expelled from the Savoy Hotel at any time. Neither is it true that I took rooms in Piccadilly for Lord Queensberry’s son,’ Wilde said emphatically denying the allegations Queensberry was spreading.

Trying to drive the point home, Clarke rephrased the question.

CLARKE: ‘Is there any truth in any of these accusations?’

WILDE: ‘There is no truth whatever in any one of them.’

Carson’s First Jab

In his introduction to the jury, Wilde had unnecessarily perjured himself, and Carson was not going to let that fact slip by the jury.

‘You stated that your age was 39,’ Carson said, looking at the floor, his brow furrowed as if deep in thought. Then he stared directly at Wilde.’I think you are over 40. You were born on 16th October, 1854?’

Wilde tried to dismiss the lie with a wave of his hand. ‘I have no wish to pose as being young. I am 39 or 40. You have my certificate and that settles the matter.’

But Carson was not going to let him off that easy. His age, and the age of Lord Albert was an important matter in this case. ‘But being born in 1854 makes you more than 40?’

Wilde conceded the point, ‘Ah! Very well.’

After asking Wilde how he met Lord Alfred, Carson turned to literary matters. Specifically, Carson wanted Wilde to address a scandalous story in The Chameleon, ‘The Priest and the Acolyte,’ which appeared in the same issue as some of Wilde’s work and Lord Alfred’s poem ‘Two Loves.’ Wilde had made it clear in the forward to Dorian Gray that he considered no literary work moral or immoral and Carson sought to test his philosophy:

CARSON: ‘You have no doubt whatever that that was an improper story?’

WILDE: ‘From the literary point of view it was highly improper. It is impossible for a man of literature to judge it otherwise; by literature, meaning treatment, selection of subject, and the like. I thought the treatment rotten and the subject rotten.’

CARSON: ‘May I take it that you think ‘The Priest and the Acolyte’ was not immoral?’

WILDE: ‘It was worse; it was badly written.’

For the next few minutes the combatants sparred over the meaning of words and philosophical arguments. Wilde was quick with a retort and Carson was just as quick to move on to something else Wilde had written. Then Carson turned to Dorian Gray.

‘I take it, that no matter how immoral a book may be, if it is well written, it is, in your opinion, a good book?’ the defence attorney asked.

‘Yes, if it were well written so as to produce a sense of beauty, which is the highest sense of which a human being can be capable,’ Wilde replied. ‘If it were badly written, it would produce a sense of disgust.’

CARSON: ‘A perverted novel might be a good book?’

WILDE: ‘I don’t know what you mean by a ‘perverted’ novel.’

CARSON: ‘Then I will suggest Dorian Gray as open to the interpretation of being such a novel?’

WILDE: ‘That could only be to brutes and illiterates. The views of Philistines on art are incalculably stupid.’

Carson began drawing Wilde in for the kill. He had the witness saying that only ‘brutes and illiterates’ would consider Dorian Gray to be a perverted novel. The question now became, just how many people could interpret Dorian Gray as documenting the homosexual love of an artist for his model?

CARSON: ‘The majority of persons would come under your definition of Philistines and illiterates?’

WILDE: ‘I have found wonderful exceptions.’

CARSON: ‘Do you think that the majority of people live up to the position you are giving us?’

WILDE: ‘I am afraid they are not cultivated enough.’

CARSON: ‘Not cultivated enough to draw the distinction between a good book and a bad book?’

WILDE: ‘Certainly not.’

Carson had landed a powerful punch. If a Philistine would interpret Dorian Gray as promoting homosexuality, and a majority of Wilde’s audience were Philistines, then the general perception of the book was that it approved of homosexuality, regardless of Wilde’s intent.

Following this through to its logical conclusion, a juror would consider that if a book was supportive of that lifestyle, the author must also be.

The barrister began reading from Dorian Gray a scene in which the painter Basil Hallward describes his feelings for Dorian.

‘Well, from the moment I met you, your personality had the most extraordinary influence over me. I quite admit that I adored you madly, extravagantly, absurdly. I was jealous of every one to whom you spoke. I wanted to have you all to myself. I was only happy when I was with you. When I was away from you, you were still present in my art.’

CARSON: ‘Do you mean to say that that passage describes the natural feeling of one man towards another?’

WILDE: ‘It would be the influence produced by a beautiful personality.’

Moving away from Wilde’s literary works, Carson tried to get Wilde to read his letters to Bosie, but Wilde refused. Carson read them himself.

‘…I cannot see you, so Greek and gracious, distorted with passion. I cannot listen to your curved lips saying hideous things to me. I would sooner-than have you bitter, unjust, hating…. I must see you soon. You are the divine thing I want, the thing of grace and beauty; but I don’t know how to do it,’ looking up from the letter, Carson asked a final question of a very pale and nervous witness. ‘Is it the kind of letter a man writes to another?’

‘It was a tender expression of my great admiration for Lord Alfred Douglas,’ Wilde replied quietly. A Knockdown

Carson had drawn blood. He had succeeded in showing that his old college rival was an egotistical artist who believed his works were beyond comprehension by the average mortal. Wilde came across as flippant and contemptuous, as if the courtroom were merely a stage for his performance. Now that his rival had been cut, Carson showed no sign of letting up. If anything, the barrister began to rain blows upon Wilde even harder. He dispensed with the literary debate and demonstrated how the Marquis of Queensberry had spent his month before the trial.

First Carson asked Wilde if he had ever dined with Alfred Wood, his blackmailer. Wilde admitted that he had. Next, Carson wanted to know, what was the nature of Wilde’s relationship with the clerk at his publisher’s office?

Wilde bristled at the insinuation.

‘I first met him in October when arranging for the publication of my books,’ Wilde replied. ‘I asked him to dine with me at the Albemarle Hotel.’

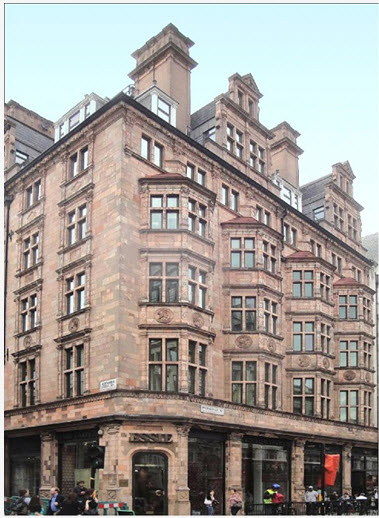

The Albemarle Hotel in Piccadilly

Carson wanted to know why a man of letters like Wilde would be interested in dinner with a mere clerk. Was it for an intellectual treat, he wondered?

‘Well, for him, yes,’ Wilde said hesitating. ‘We dined in my own sitting-room, and there was one other gentleman there.’

‘On that occasion did you have a room leading into a bedroom?’ Carson asked

‘Yes.’

‘Did you give him whiskies and sodas?’

‘I suppose that he had whatever he wanted. I do not remember.’

Wilde denied having any physical relationship with the young man, and Carson was content to let the matter drop. He had plenty more ammunition. How did Oscar Wilde meet the young man who sold newspapers at the kiosk in Worthing?

‘One day when the fishermen were launching a boat on the high beach, Conway, with another lad, assisted in getting the craft down to the water. I said to Lord Alfred Douglas, ‘Shall we ask them to come out for a sail?’ He assented, and we took them. After that Alphonse and I became great friends, and it is true that I asked him to lunch with me. He also dined at my house, and lunched with me at the Marine Hotel.’

CARSON: ‘Was his conversation literary?’

WILDE: ‘On the contrary, quite simple and easily understood. He had been to school where naturally he had not learned much.’

A very rattled Wilde then committed the second sin of a witness in court (the first being lying on the stand): He gave more in his answer than the question required.

‘It is not true that I met him by appointment one evening and took him on the road to Lancing, kissing him and indulging in familiarities on the way,’ he asserted.

Carson produced a series of gifts Wilde had purchased for the newsboy, including a cigarette case, a photograph of Wilde, a signed edition of one of his books, and a silver-topped walking stick.

His opponent figuratively on the ropes, Carson jabbed again, landing a stinging blow. Regarding a boy named Walter Grainger, Carson asked, ‘Did you kiss him?’

Without thinking of the consequences, Wilde replied.

‘Oh, dear no,’ he said. ‘He was, unfortunately, extremely ugly. I pitied him for it.’

Carson took on an exaggerated look of confusion. ‘Was that the reason why you did not kiss him?’

Wilde refused to answer directly.

CARSON: ‘Why sir, did you admit this boy was extremely ugly?’

WILDE: ‘For this reason. If I were asked why I did not kiss a doormat, I should say because I do not like to kiss doormats. I do not know why I mentioned that he was ugly, except that I was stung by the insolent question you put to me and the way you have insulted me through this hearing.’

But Carson was relentless. Three more times Carson asked the same question, each time Wilde was unable to answer. Carson then began sharply repeating, ‘Why? Why?’ Carson’s repeated sharply: ‘Why? Why? Why did you add that?’

Finally Wilde was forced to admit he had been acting in a cavalier manner during the questioning. At the edge of exasperation he said, ‘You sting me and insult me and try to unnerve me; and at times one says things flippantly when one ought to speak more seriously. I admit it.’

CARSON: ‘Then you said it flippantly?’

WILDE: ‘Oh, yes, it was a flippant answer.’

Much has been made of Edward Carson’s cross-examination of Oscar Wilde. He matched Wilde in intelligence and he clearly conducted a skilful interrogation. But was it one for the ages? Richard Ellman, a Wilde apologist, thinks not.

‘Carson had so much evidence, and of such a kind, that he only needed to be persistent, not clever.’

Regardless, Edward Carson’s inquisition flattened Oscar Wilde.

Edward Carson

Edward Carson

The Next Round

The match was clearly over and Queensberry had won on unanimous cards. Reeling, Wilde returned to his rooms and with friends pondered his fate. He was urged to flee the country by everyone, including his solicitors, who said they could keep the trial going in his absence to give him time to get out of the country.

Clarke did give Wilde one alternative, which Wilde grabbed at. There was a chance, Clarke said, that Queensberry would agree to a verdict of not guilty on the charge of libel, and drop the question of whether he had called Wilde a sodomite for the good of the public. If he did this, there was a chance no criminal charges against Wilde would be filed. By the time Wilde had decided on a course of action, the last train for Dover and the continent had left London, making Oscar’s decision for him.

The next morning, with Oscar absent from the courtroom Carson began mounting his defence of Queensberry. He was barely through his opening statement and about to list the boys who were prepared to testify against Wilde when Clarke arose from his chair and asked the court’s permission to confer with opposing counsel. He offered the deal Wilde had agreed upon, but Carson would not relent. Queensberry wanted Wilde burned to the ground, the ashes scattered and the fields sown with salt. It was all or nothing. Clarke had no choice but to agree.

Arrest and Destruction

His boot on Wilde’s neck, Queensberry prepared to deliver the coup de grace. He told his solicitor to send the notes from the libel trial and all of the evidence his private detectives had turned up about Wilde’s interest in boy prostitutes to Scotland Yard. This move left authorities with no choice but to arrest Wilde and charge him with gross indecency. Next Queensberry sent word to Wilde alerting him to what he had done. He ended the note with a threat. ‘I will not prevent your flight, but if you take my son with you, I will shoot you like a dog,’ Queensberry wrote.

Wilde’s wife, Constance, and son Cyril

Again Wilde wavered on whether he should flee the country. His wife Constance urged him to leave England, as did some of his friends. Few, if any, argued that he should stay and face the charges. But Wilde’s ego was such that he couldn’t bear being known as a coward and outlaw. He was deathly afraid of prison, but even more so of the disgrace that faced a gentleman who ran away from legal troubles.

At 5 p.m. the day after his libel trial had ended in disaster, Wilde learned that an arrest warrant had been issued from Bow Street. An hour and ten minutes later there was a knock at the door of his hotel room and several plainclothes officers entered.

‘Will I be allowed bail?’ an obviously intoxicated Wilde asked his captors.

Witnesses said Wilde’s complexion was particularly ashen when he learned from police that he would probably not receive bail before the trial. Taken to Bow Street, Wilde entered a not guilty plea, bade his friends and supporters farewell and was taken into custody.

The world quickly crashed around Wilde. His name was taken down from the marquees where his two plays had been showing, to packed houses, and an American tour of ‘A Woman of No Importance’ was cancelled. A sale of his work ‘Salome’ fell through. His ‘friends’ backed away from him and refused to help post bond, even though a magistrate had set no amount. Others who had been named in the papers as friends of Wilde fled the country lest they be charged themselves. Those who did stand by him were ostracized by London society and were evicted from apartments and expelled from clubs.

The Marquis had one more opportunity to punish Wilde. He had spent 600 pounds defending himself against the libel charges and had a judgment against Wilde to pay the court costs. He demanded payment in full, forcing Wilde into bankruptcy. Some of Oscar’s most prized possessions, including first editions of his own books, and artworks by his friends Whistler and Aubrey Bearsdley were seized and sold at auction to pay the bill. Oscar himself was brought into bankruptcy court in chains to answer Queensberry’s charges. Once his estate was liquidated and Oscar Wilde was returned to jail to await trial, he had lost everything.

The First Trial

A grand jury indicted Wilde and Alfred Taylor, the local procurer whose name had come up several times, in Queensberry’s investigation, with indecency and sodomy. The evidence against Taylor was at least as damning as that against Wilde, and the young man was under tremendous pressure to turn state’s evidence against Wilde. Taylor declined.

On April 26, 1895, the Crown began presenting its case against Wilde. There were 25 counts against each of the men, ranging from gross indecency to conspiracy to commit gross indecency and sodomy.

The prosecutor, Charles Gill, another Oxford classmate of Wilde’s, called a succession of young men, some working class gentlemen and others of more ill repute.

The most damaging witnesses were the brothers Charles and William Parker. admitted prostitutes, who had apparently been brought into the trade by Alfred Taylor. Parker’s testimony was particularly harmful.

CHARLES PARKER: ‘Subsequently Wilde said to me. ‘This is the boy for me! Will you go to the Savoy Hotel with me?’ I consented, and Wilde drove me in a cab to the hotel. Only he and I went, leaving my brother and Taylor behind. At the Savoy we went first to Wilde’s sitting room on the second floor.’

PROSECUTOR GILL: ‘More drink was offered you there?’

PARKER: ‘Yes, we had liqueurs. Wilde then asked me to go into his bedroom with him.’

GILL: ‘Let us know what occurred there?’

PARKER: ‘He committed the act of sodomy upon me.’

In the days leading up to the trial and during the first few days, Bosie was a daily visitor to Wilde in jail. However, Sir Edward Clarke, who was defending Wilde pro bono, felt it was dangerous having Lord Alfred in London and demanded that he leave the country, lest he be subpoenaed to testify.

Queensberry had done everything he could to keep his son’s name out of the investigation and trial, but even he could not guarantee Bosie’s safety now. Reluctantly, Lord Alfred joined Wilde’s other gay friends in Calais.

Some of the other men who testified against Wilde included Alfred Wood, who had blackmailed him for the letters he sent to Bosie, and Robert Clibborn, who had earlier blackmailed both Wilde and Bosie. Others testified to Taylor’s odd habit of keeping the shades drawn in his ‘perfumed’ apartment and to having young boys who dressed as women there.

The circumstantial evidence against the men was substantial. A chambermaid testified to faecal stains on a sheet in Wilde’s rooms, another man told jurors that he had come to give Wilde a massage only to find a young man already asleep in Wilde’s bed.

The high point of the first criminal trial came during Wilde’s cross-examination by prosecutor Gill. It showed the world that, while Wilde might have appeared physically broken, his spirit was undaunted. The interaction came as Gill was asking Wilde about his literature.

‘What is ‘The Love that dare not speak its name?” Gill asked, undoubtedly hoping for a straightforward response. It is unlikely he was prepared for Wilde’s off-the-cuff response.

”The Love that dare not speak its name’ in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the “Love that dare not speak its name,” and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.’

Oscar Wilde

Although he was adamantly against homosexuality, Justice Sir Arthur Charles was not one to allow the seriousness of the accusation to trump the law and before giving the case to the jury, he dismissed the conspiracy charges, as there was never any evidence offered that would show Taylor and Wilde conspired together to commit sodomy. The majority of the charges dropped, then, Sir Arthur asked the jurors to retire to consider the evidence.

The jury was out just more than four hours and returned to the courtroom undecided on most counts. They had agreed on one, and found Taylor and Wilde not guilty of gross indecency. On the others they were hopelessly deadlocked, either 11 to 1 or 10 to 2 for conviction, depending on which newspaper one read.

For a moment, Wilde must have thought the worst was over. He was wrong. Gill immediately stood and announced the Crown’s intention to retry the case. This time, however, Wilde was granted bail.

There were many on both sides that wanted the incident forgotten and begged Gill’s supervisor not to retry Wilde. He was a beaten man; his estate was bankrupt and no matter how well he wrote in the future, no theatre would produce his plays and no publisher would touch his literature. Oscar Wilde had been drummed out of polite society and was expected to leave the country to wither and die somewhere else, awash in his shame. But the pressure on the Crown was too great and a trial was ordered to begin forthwith.

The Second Trial

Free from jail, Oscar found he couldn’t rent rooms in London and was forced to go to his estranged brother for help. They had quarrelled for years, but this time his brother was willing to overlook differences and gave Oscar a cot in a storage room. In many ways it was an omen of things to come for Wilde.

The second trial was a repeat of the first. The same witnesses came forward and told the same stories. One of the few surprises to come out was that each of the witnesses against Wilde had been receiving a five pound stipend from the prosecution since the beginning of the first trial. The Parkers repeated their claims that they had engaged in sodomy with Wilde for money. Edward Shelley, the publisher’s clerk whom Wilde had tried to seduce, also testified about his dinner with Oscar. The letters from Oscar to Bosie were introduced into evidence and Oscar was forced to try and defend them.

‘The last day of the trial, 25 May, was the Queen’s birthday,’ wrote Ellman. ‘(The prosecutor) made his final speech…He raked Wilde over; he dealt with the suspect letters to Douglas, the payment of blackmail to Wood, the relations with Taylor, Wood, Parker…which he insisted corroborated each other.’

Sir Edward Clarke rose to sum up the case for the defence. It was more a plea for mercy.

‘This trial seems to be operating as an act of indemnity for all the blackmailers in London,’ he said. ‘If on an examination of the evidence you, therefore, feel it your duty to say that the charges have not been proved, then I am sure that you will be glad that the brilliant promise which has been clouded by these accusations…(has) been saved by your verdict from absolute ruin.’

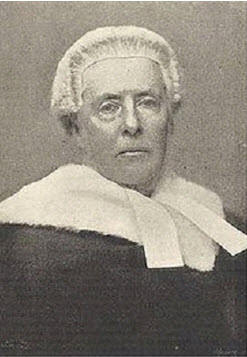

In the English system, the judge is charged with summing up the facts of the case for the jurors, and then presenting them with the questions of guilt or innocence. Justice Wills was a homophobe and, despite his education, one of the Philistines Wilde had railed against in his first trial. Wills was as sober and unimaginative a man as ever sat on the bench, and he ranked sodomy just slightly below murder in terms of atrocity. His summation proved this. He spoke of the letters to Bosie in the most unflattering terms and finished by saying, ‘This is the worst case I have ever tried.’

Justice Wills

Two hours after being given the case, the jurors returned. They found Wilde guilty on all counts save one involving Edward Shelley. Justice Wills then addressed the convicts.

‘Oscar Wilde and Alfred Taylor, the crime of which you have been convicted is so bad that one has to put stern restraint upon one’s self to prevent one’s self from describing, in language which I would rather not use, the sentiments which must rise to the breast of every man of honour who has heard the details of these two terrible trials.’

Wills went on for several minutes rebuking the two men before passing sentence.

‘I shall, under such circumstances, be expected to pass the severest sentence that the law allows. In my judgment it is totally inadequate for such a case as this. The sentence of the Court is that each of you be imprisoned and kept to hard labour for two years.’

Standing in the dock, Wilde blanched and reeled as if he had been struck. His face contorted in pain, he was heard to mutter, ‘My God. My God. May I say nothing, My Lord?’

Wills merely waved his hand at the jailers, gathered his papers and walked out as the prisoners were led away.

Prison and After

‘Hard labour’ in an English prison was no euphemism. Every prisoner was expected to walk six hours a day on a treadmill in 29-minute increments with five-minute breaks. The distance to be covered was the equivalent of a 6,000-foot incline. Taken from the Old Bailey to Newgate Prison, Wilde had his belongings taken from him and was outfitted with grey prison togs with their distinctive black arrows pattern.

Shortly after being read the rules of the prison system, utter silence at all times, Wilde was taken to his cell and fed a typical meal of watery porridge and a slice of bread. From Newgate he was taken to Pentonville Prison, where he was placed on the treadmill. At night he was returned to his cell, where he slept on a wooden plank without mattress.

Diet at Pentonville consisted of cocoa and bread for breakfast, soup or sliced meat for dinner, and suet and potatoes for tea. Exercise consisted of walking in a circle single-file silently for one hour a day. He was required to attend chapel every morning and twice on Sundays. Visitors were allowed once every three months for 20 minutes. Physical contact was out of the question, as were books, paper and pen.

‘Already Wilde has grown much thinner,’ wrote a contemporary newspaper. ‘He has great difficulty in getting to sleep, and from time to time he loudly bemoans the bitterness of his fate.’

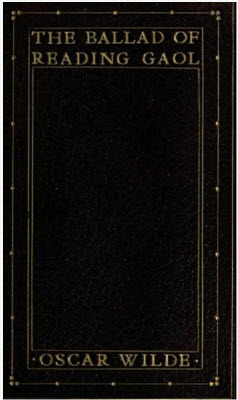

Book cover: The Ballad of Reading Gaol

Slowly, over time, Wilde adapted to prison and it to him. He was later allowed writing materials and was transferred to better surroundings. It was in Reading that he developed one of his best works, ‘A Ballad of Reading Gaol.’ The Ballad is an allegorical biography of Wilde’s downfall and was prompted by Wilde’s witnessing of an execution. In it, he wrote what could almost serve as his obituary:

Dear Christ! the very prison walls

Suddenly seemed to reel,

And the sky above my head became

Like a casque of scorching steel;

And, though I was a soul in pain,

My pain I could not feel.

I only knew what haunted thought

Quickened his step, and why

He looked upon the garish day

With such a wistful eye;

The man had killed the thing he loved,

And so he had to die.

Yet each man kills the thing he loves,

By each let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

Wilde served his time and was released. His works had enjoyed a small revival because of his notoriety, but he was still bankrupt and persona non grata in London. Over time, with the help of his friends, he managed to bring his estate out of bankruptcy. He fled to France where Bosie was waiting for him. But Wilde’s ardour had cooled in the two years in prison. He did not hate Lord Alfred, but the passionate love of the years before was gone.

Wilde’s other prison work, ‘De Profundis,’ was a biography, a confession and absolution for Bosie. The two men saw little of each other in the first months of Wilde’s freedom but they did exchange a number of letters, most lost to history.

The love that had brought Wilde down in England was somewhat rekindled in Europe much to the dismay of Wilde’s wife and his friends. It alienated Wilde and Bosie from everyone who had stood with Oscar over the years and it would prove too painful for even Wilde and Lord Alfred to bear. They separated after a short time in Europe. Wilde continued to write and entertain, and be his egotistical self, up until the end. He lived long enough to see the ‘Ballad of Reading Gaol’ published in London anonymously to great success, and was convinced by his publisher to add his name to the poem for the seventh printing.

He died in 1900.

Oscar Wilde, remembered in stained glass at Westminster Abbey

Much of Wilde’s writing is autobiographical, not so much in relation of events, but in thoughts and desires. ‘Dorian Gray’ is probably the most self-reflective. One of its characters expresses Wilde’s philosophy of life: ‘We can have in life but one great experience at best, and the secret of life is to reproduce that experience as often as possible.’

FIRST PUBLISHED BY OPC GLOBAL 5 SEPTEMBER 2012 AND REPUBLISHED 28 JUNE 2014

NB: Some images retrieved from Google, will remove at owner’s request.

Book cover: The Picture of Dorian Gray

Book cover: The Picture of Dorian Gray

Marquis of Queensberry

Marquis of Queensberry

Sir Edward Clark, Wilde’s Barrister-in-law

Sir Edward Clark, Wilde’s Barrister-in-law

Edward Carson

Edward Carson