PARERE PRO VERITATE

COMPATIBILITY ISSUES BETWEEN MAGNA CARTA (1215) Ch.54 AND THE YOUTH JUSTICE AND CRIMINAL EVIDENCE ACT 1999 S.53 AND 54 IN CERTAIN MURDER TRIALS

The accepted and settled rule of law is that a witness is competent if he is able to give evidence and compellable if he may lawfully be required to give evidence. Competent witnesses are in the normal course but not necessarily compellable. However, the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 S.53 enacted a general rule to the effect that all persons are competent to give evidence in criminal proceedings. This is, however, subject to just two exceptions which are specified in subsection (3) and (4) of s.53.

SECTION 53[1]

Competence of witnesses to give evidence.

1) At every stage in criminal proceedings, all persons are (whatever their age) competent to give evidence.

2) Subsection (1) has effect subject to subsections (3) and (4).

(3) A person is not competent to give evidence in criminal proceedings if it appears to the court that he is not a person who is able to —

(a) understand questions put to him as a witness, and

(b) give answers to them which can be understood.

(4) A person charged in criminal proceedings is not competent to give evidence in the proceedings for the prosecution (whether he is the only person, or is one of two or more persons, charged in the proceedings).

(5) In subsection (4) the reference to a person charged in criminal proceedings does not include a person who is not, or is no longer, liable to be convicted of any offence in the proceedings (whether as a result of pleading guilty or for any other reason).

Determining the competence of witnesses.

(1) Any question whether a witness in criminal proceedings is competent to give evidence in the proceedings, whether raised—

(a) by a party to the proceedings, or

(b) by the court of its own motion, shall be determined by the court in accordance with this section.

(2) It is for the party calling the witness to satisfy the court that, on a balance of probabilities, the witness is competent to give evidence in the proceedings.

(3) In determining the question mentioned in subsection (1) the court shall treat the witness as having the benefit of any directions under section 19 which the court has given, or proposes to give, in relation to the witness.

(4) Any proceedings held for the determination of the question shall take place in the absence of the jury (if there is one).

(5) Expert evidence may be received on the question.

(6) Any questioning of the witness (where the court considers that necessary) shall be conducted by the court in the presence of the parties.

The test according to Statute is on the balance of probabilities.

It follows that the time to raise any objections on competency is before any witness is sworn. There are a number of authorities dating back to the 18th century [Wollaston v Hakewill (1841) 3 Scott N.R 593 and Bartlett v Smith (1843)]. More recent authorities R v Hampshire (1995) 2 Cr App R 319 CA simply affirm the decisions taken over one hundred years past.

The golden rule that the judge and only the judge can determine the competency of a witness remains. The settled manner upon which should occur is by a voir dire from the witness or from others.

The jurisprudence regarding a spouse or a civil partner is covered by the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 s.80[1] and affirms in essence that a spouse is not compellable to give evidence against a partner.

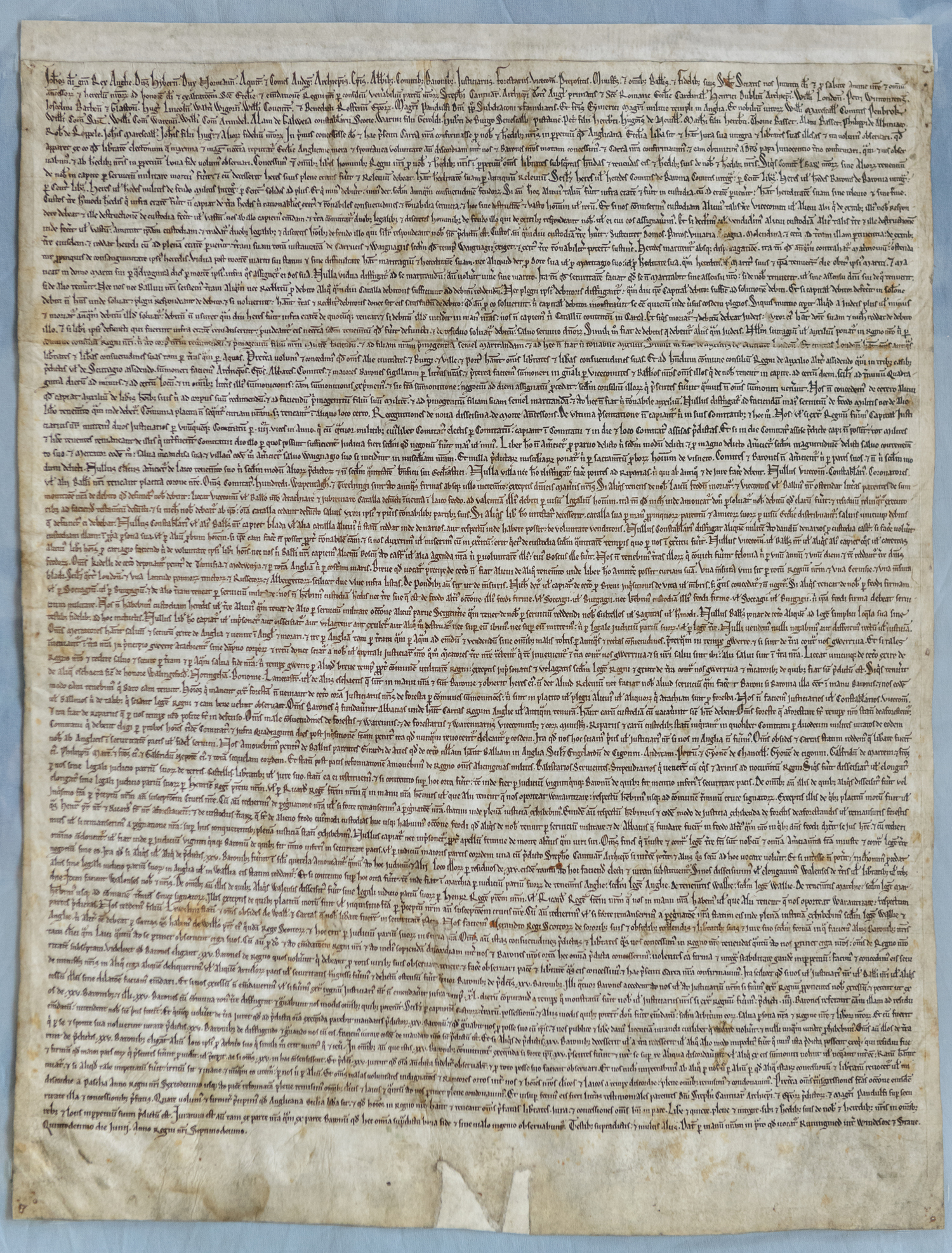

Has the law and jurisprudence though failed to add another vital matter that dates back 805 years? Magna Carta was written in 1215 using gall-ink on parchment slightly oblong, almost square. The Magna Carta was first known as the ‘big charter’ which was intended to distinguish it from another important, much shorter, and less known legislation called the ‘Forest Charter’.

It is uncertain how many copies were made of the Magna Carta but only four copies remain today. One was nearly destroyed when a pre-British Library copy was kept in an outhouse store on the site where Westminster School is now located and a fire broke out which damaged both the Magna Carta and the Beowulf manuscript.

Magna Carta is sovereign statute and cannot be repealed.

Magna Carta Chapter 63[2] clearly states:

“Wherefore we wish and firmly command that the English church shall be free, and the men in our realm shall have and hold all the aforesaid liberties, rights and concessions well and peacefully, freely and quietly, fully and completely for them and their heirs of us and our heirs in all things and places forever, as is aforesaid.

Magna Carta, 1215

Any Chapter within Magna Carta is incapable of being repealed and any government attempting to do so would be committing a criminal offence.

Whilst Chapter 40 and Chapter 55 are much-cited and jurists worldwide make daily references to them Chapter 54 has been somewhat overlooked.

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1984/60/section/80

Yet chapter 54 is of considerable significance to those practising criminal law and involved in murder trials.

Chapter 54:

“No man shall be taken or imprisoned upon the appeal of a woman for the death of anyone except her husband.”

In essence, in the past 805 years anyone who has been ‘taken’ or ‘imprisoned’ and, possibly, even executed for the offence of murder where the only witness was a woman and the victim was not her husband must be acquitted/pardoned.

In any trial today the procedure is an application to the trail judge citing Chapter 54 and as reprehensible as it may be the law must be applied.

For the likes of Jeremy Dein Q.C and Sasha Wass Q.C who are both of the highest calibre of Counsel to Her Majesty and who regularly do battle on the BBC ‘Murder, Mystery and My Family: Case Closed?’ it will add yet another ingredient to their task.

Anyone who is convicted of murder where the only evidence is from a ‘woman’ {no other evidence at all] should consider filing an appeal against conviction or if there has already been an appeal then an application under the Criminal Procedure Rule 36.15.

Anyone who has ancestors convicted in a criminal manner can apply to the Secretary of State for Justice under the prerogative of pardon.

Understandable, applications may well be treated with indignance and scorn especially if the evidence offered by the ‘woman’ was indeed cogent, probative and believable. That, however, is not the test under Chapter 54 of Magna Carta 1215. It is distinguishable from the test of the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 S.53 which requires a ‘determination.’.

Chapter 54 of Magna Carta is truly simple and requires no assistance from the Interpretation Act 1889 or the more recent 1978.

The defence has only to establish that the victim was not the husband of the ‘woman’ witness. No court can, should, or even attempt, to violate Magna Carta 1215 and no government should attempt to violate Magna Carta 1215 and no government should attempt to cure or repeal any of the chapters.

Giovanni Di Stefano

8/8/2020

NB: Some images retrieved from Google, will remove at owner’s request.