The bouncing baby boy who was to become one of the most prolific serial killers in recorded history was born to Nottingham working-class parents Vera and Harold Shipman on 14 June 1946.

The second of four children, young Harold, nicknamed Fred by his family, lived in the family home on a council estate in Bestwood.

His beloved mother Vera was to have a huge impact on young Harold’s life. He was always the favorite of her children – the one she saw as having a more promising future than that of his siblings.

A neighbor remembers: “Vera was friendly enough, but she really did see her family as superior to the rest of us. Not only that, but you could also tell Harold (Freddy) was her favorite — the one she saw as the most promising of her three children.”

Vera chose Harold’s friends, he didn’t question that his mother should tell him who he could play with, and when. To further distinguish him from other, lesser, boys, he was made to dress differently.

Whilst other youngsters were able to dress casually, young Harold had to wear a tie. The combination of these things set him aside from his peer group and feeling this distance, he began to believe his mother’s claims that the family were better than others in their social class.

In his early school years, Harold was quiet but bright. By the time he reached Pavement Grammar school in Nottingham, he had become rather a plodder academically.

In 1963, when Harold was a 17-year-old studying for his A-levels, his beloved mother Vera was dying from lung cancer. In the final months of her life, Harold would hurry home from school to sit with her, make her a cup of tea and hold her hand.

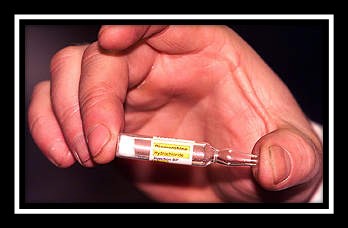

Shipman watched with fascination as, towards the end of Vera’s life, when she was in great pain, relief of her suffering would come in the shape of the family doctor and a needle.

He noted how after each visit, during which Vera was injected with morphine, she would find sweet relief and be able to rest comfortably – if only for a while.

This was a scene that would remain with Harold Shipman for the rest of his life.

A scene he would re-create too re-live over and over and over again.

When Vera died in 1963, Harold was bereft. She was the only one that had made him feel special and now she was gone.

In 1965, Harold was accepted at Medical School. It is no surprise, in light of how he’d seen his mother suffer only to rally for a time after her ‘medicine’ as she called the morphine injections that he’d decided to become a doctor.

Today, Harold’s teachers and fellow students at Leeds University barely remember him. Those that do recall claimed he seemed to look down upon them.

One said: “It was as if he tolerated us. If someone told a joke he would smile patiently, but Fred never wanted to join in. It seems funny, because I later heard he’d been a good athlete, so you’d have thought he’d be more of a team player.”

Fred was indeed a good athlete. The one place where his personality changed, not always for the better, was on the football field. Here at last was somewhere it was acceptable to show emotion, to release pent-up aggression and frustration. Even here, however, Harold was driven to win – he was never a gracious loser.

No longer under his mother’s influence, Harold became a little more sociable whilst at medical school. A teacher remembers, “I don’t think he ever had a girlfriend; in fact he took his older sister to school dances. They made a strange couple, but then, he was a bit strange — a pretentious lad.”

Then, loner Harold met Primrose Oxtoby, a farmer’s daughter. Like Fred, Primrose’s mother had chosen her friends and restricted her movements.

Harold and Primrose, who was a ‘homely’ looking girl was glad to have found a suitor, and they quickly became inseparable. Before long, Primrose became pregnant and the couple decided to marry during Harold’s first year at university, Primrose was five months pregnant when they wed.

By 1974, Harold and Primrose were the parents of two children. Harold had graduated from university and joined a medical practice in Todmorden in Yorkshire.

Here Fred underwent a metamorphosis. He became a respected and outgoing member of the community. He became likeable and was liked in return by his fellow doctors and patients.

The other staff where he worked, however, saw a different side to young Dr. Shipman. When speaking to them, he was regularly rude and made them feel ‘stupid.’ This was reputedly his favorite word when dealing with junior staff – a word used to describe anyone he disliked – they were all ‘just stupid’.

His appointment at the Todmorden practice came to an abrupt end when it was discovered that Harold had become addicted to the painkiller Pethedine.

He would regularly forge prescriptions for large amounts of the drug, which he would then inject. When he was forced to leave the surgery, he entered a drug rehab program. A subsequent inquiry into his behavior saw him receive a conviction for forgery and a £600 fine. He was not struck off the medical register and kept his status as a doctor.

In 1979, Harold joined the Donneybrook Medical Practice in Hyde, Greater Manchester. As he had before, he became a respected member of the community and ingratiated himself with other practice doctors.

Although it was mostly kept from the other medics and certainly from his patients, Harold was again combative and confrontational with ‘stupid’ junior staff. He would embarrass and belittle them for his own pleasure. He manipulated the older, more experienced, doctors in the practice to get his own way.

In short, Harold Shipman, not yet thirty-years-old had become a control freak.

No one, however, could level blame at Harold for being lazy. As in his previous position, he was enthusiastic about his job and worked hard.

A senior partner in the practice, remembered particularly appreciating Harold’s contribution, as he was fresh out of medical school, in offering up-to-the-minute medical information.

Harold Shipman was to remain on the staff at Donneybrook for almost two decades. During that time, he was interviewed for Granada TV’s World in Action program, discussing how the mentally ill should be treated within their local community.

In 1993, by which time he and Primrose had four children, Harold opened his own GP surgery in Hyde’s Market Street and continued to practice as a family doctor.

In early 1998, prompted by one of the owners of Frank Massey and Son’s funeral parlor, Dr. Linda Reynolds from Brooke Surgery in Hyde, contacted John Pollard who was the coroner for the South Manchester District.

Dr. Reynolds expressed concerns about the higher-than-average death rate amongst Harold’s patients. She was particularly concerned, she said, about the large number of cremation forms being produced for elderly women.

The matter was brought before the police who were unable to find sufficient evidence to bring lasting charges against Dr. Shipman.

Later, the police were to be blamed for assigning officers with little experience to investigate the case.

Between the time when the investigation was abandoned in April 1998 and before his arrest in autumn of the same year, Harold went on to kill three more patients.

One was the former Lady Mayor of Hyde, Kathleen Grundy, who died ‘suddenly’ at 81-years-old. Harold was the last person to see Mrs. Grundy alive and he later signed her death certificate recording ‘old age’ as cause of death.

Mrs. Grundy’s daughter, Angela Woodruff, was a lawyer and as such, had always handled her mother’s affairs. When she found out that her mother had made a will which excluded her and her children and left £386,000 to Harold Shipman, she became highly suspicious.

She became convinced that Dr. Shipman had killed her mother and had penned a ‘new’ will to benefit financially from her death.

The police were notified, and they began an investigation which saw Mrs. Grundy’s body exhumed. When examined, it was discovered she had died from an overdose of morphine, administered three hours prior to her death.

When Harold’s home was raided, amongst suspicious items collected by the police were an odd collection of jewelry and an old typewriter which upon examination, proved to be the instrument on which the forged will had been written.

Medical records seized in the raid showed that Mrs. Grundy’s death was unlikely to be an isolated incident. The police made the investigation of certain cases a priority. These included, in particular, those as yet alleged victims who had not yet been cremated but had died following a visit from Dr. Shipman.

It was found that in a large number of cases, Dr. Shipman had urged grieving relatives to cremate their loved ones, stressing that no further investigation into their deaths was necessary, even when patients had died from illnesses not previously known by family members.

Following an interview in Ashton-under-Lyme police station on September 7 1998, Harold Shipman was charged with the murder of Kathleen Grundy. The following day, at an appearance at Tameside Magistrates Court, he was also accused of forging her will. He was refused bail.

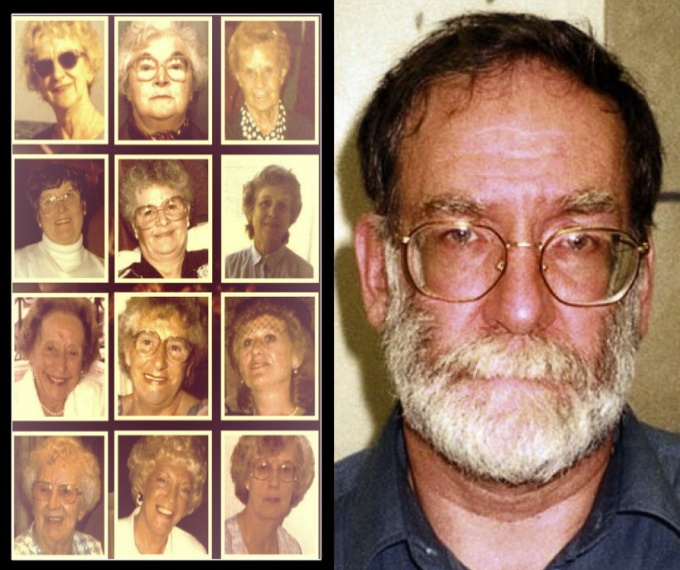

Throughout the remainder of 1998, the bodies of the following women were exhumed.

- Marie Quinn, 67, who died in July 1996.

- Jean Lilley, 59, who died in April 1997.

- Ivy Lomas, 63, who died in May 1997.

- Muriel Grimshaw, 76, who died in July 1997.

- Bianka Pomfret, 49, who died in December 1997.

- Winifred Mellor, 73, who died in May 1998.

- Joan Melia, 73, who died in June 1998.

In 1998, Harold was charged with murdering Mrs. Quinn, Mrs. Lomas, Mrs. Pomfret, Mrs. Mellor and Mrs. Melia.

In February 1999, Harold was charged with murdering Mrs. Grimshaw and six other patients who had already been cremated:

- Marie West, 81, who died in March 1995.

- Lizzie Adams, 77, who died in February 1997.

- Laura Wagstaff, 81, who died in December 1997.

- Norah Nuttal, 65, who died in January 1998.

- Maureen Ward, 57, who died in February 1998.

Morphine toxicity was found to be the cause of death in almost all cases of those who had died at Shipman’s hand.

Harold went on trial at Preston Crown Court charged with forging Mrs. Grundy’s will and murdering 15 patients.

Throughout the trial, Harold’s ‘haughty demeanor’ did little to help his case. Following a meticulous summation by the judge and a reminder to the jury that no one had actually witnessed Dr. Shipman kill any of his patients, on January 31, 2000, he was convicted on all counts.

As well as a four-year sentence for will forgery, the judge passed fifteen life sentences, commuted to a ‘whole life’ sentence.

This effectively removed any hope or possibility of parole for Harold. He was jailed for the remainder of his life at Durham Prison.

At the verdict, a collective shudder went through the medical community. This was to prove insignificant, however, in light of further investigations into case histories of the deceased that had been on the patient list of ‘Dr. Death’, as the media had dubbed him.

Professor Richard Baker of the University of Leicester conducted a clinical audit. He examined the pattern of deaths in Dr. Shipman’s practice and compared them against those in other surgeries.

He found that the rate of death amongst Harold’s elderly patients was significantly higher. Deaths appeared to be clustered around certain times of day. He also found that the doctor had been in attendance during a disproportionately high number of deaths.

The completed audit estimated that Dr. Harold Shipman, over a period of 24-years, may have been responsible for the deaths of at least 236 patients in his care.

An inquiry commission chaired by Dame Janet Smith, High Court Judge, examined the records of some 500 patients who had died whilst in Shipman’s care. The 2,000 page report concluded that it ‘was likely’ he had murdered at least 218 patients. This however, was estimation; there was insufficient evidence to be more precise.

Harold was ‘addicted to killing’ speculated the commission. It also criticized the police handling of the case, in particular the missed opportunities by assigning inexperienced officers to the original investigation.

It was further speculated that Harold may have killed his first victim within just months of obtaining his medical license. The untimely deaths of some of Dr. Shipman’s patients prior to 1975, however, were never officially proven.

During this time, Harold remained in his cell at Durham Prison. He maintained his innocence of all charges. Primrose, his loyal wife, their sons at her side, staunchly defended her husband.

In June 2003, he was moved to Wakefield prison. It was here on January 13, 2004, the eve of his 58th birthday that Dr. Harold Shipman was found dead – hanging from bed sheets tied to the window bars in his cell.

Harold Shipman had committed suicide. That was the story fed to the media – the story they reported and the story the world was directed to accept, blindly, as the truth. OPC Global News and Media can now reveal a different story which took place behind the scenes.

Not everyone believed all they were instructed to believe, however, about ‘Dr. Death’s wrongdoing’s’ or about his own demise.

Before Shipman’s death, Giovanni Di Stefano better known as the Devil’s Advocate had been concerned over the way Shipman’s conviction was obtained.

He had been working on an appeal on Shipman’s behalf and had been awaiting the outcome of a retrial case at Chelmsford Crown Court, which succeeded.

“Based upon that precedent, there would be further grounds of appeal for Dr. Shipman,” Mr. Di Stefano told Sky News, after Harold Shipman’s death.

“Having succeeded in that case and having notified Dr. Shipman and sent him a copy of the transcript that we had succeeded, it is extremely strange, to put it mildly, that a person who at last is given a chance, not much of one, of succeeding in getting an appeal off the ground would then suddenly kill himself.

“A person who has a ground of appeal, a precedent in the Court of Appeal to allow themselves to appeal, suddenly commits suicide a day before his birthday?

“A person who is supposed to be the biggest mass murderer in the United Kingdom, with so many deaths on his hands allegedly … is left unattended in this way?

“We need to make inquiries as to whether anybody had gone to his cell to see what was happening in the middle of the night. We just don’t know.”

“Something is not really quite right there.”

Harold Shipman himself had previously told prison officers, “I am not going to commit suicide because I am going to fight to prove my innocence.”

In an interview with the BBC, Mr. Di Stefano said, “One of the areas that caused me grave causes for concern on the safety of the conviction is the question of the defence being allowed to hold separate postmortems for eleven of the victims. A postmortem was carried out on the late Mrs. Grundy but on the others, only a review of the evidence of the Crown was permitted.”

By refusing the defence team a second-post mortem examination on the eleven victims, Harold Shipman was denied a fair trial under the law of England and Wales, Mr. Di Stefano argued.

If Shipman did not receive a fair trial, his conviction was unsafe.

“If this man [Shipman] is to be condemned…let’s do it in a manner that is lawful, and we can be satisfied that we have the right man.”

Mr. Di Stefano pointed out the Crown conceded that the evidence given by the forensic toxicologist at the original trial was “potentially flawed.”

He said, “Is it safe to assume that because [diamorphine] is in one of the victims and you are prohibited from having a post-mortem on the others that it is a safe conviction?”

Many people came forward to Mr. Di Stefano to offer an insight into both the manner in which Harold was accused of murdering patients, and his apparent suicide.

One such call was from James Spensley, a parliamentary candidate for the Isle of Wight.

Mr. Spensley said he was “extremely keen to talk” and believed he could be of “enormous help” in the case of Dr. Harold Shipman.

He stated that in his previous occupation, he was “directed to administer morphine over many years on numerous occasions by the MO”.

Harold Shipman’s son broke the silence his family had until then maintained.

Samuel Shipman, speaking for the rest of his family, said they had always believed Harold to be innocent. He didn’t believe his father took his own life, especially in the light of the appeal which had just been approved. He believed suicide was simply something his father would never consider.

Di Stefano received a letter arrived from a man who had been in prison with Harold Shipman in Wakefield. OPC Global News and Media now exclusively reveals the content of the letter.

Mr Rodney King and Shipman spent many hours together. They came to rely upon each other for company and each considered the other a good friend.

In his letter, Mr. King told how he was victimized by prison guards for being friendly with Shipman.

He said that Harold remained calm and good-humored, even though guards went out of their way to make his life in prison difficult

One day, the man who ‘lived’ as King put it, in the cell next to Harold’s, a prisoner called Shepp, called him over. He told King that he and other prisoners were staying away from Shipman, warning King he should do the same, because they “didn’t want any blood spilled on them when Shipman finally got done by officers”.

King also said that, in his position as his closest friend in prison, he could see that Shipman “was preparing to live, not to die”.

King firmly believed that Harold Shipman did not take his own life.

He believed that his friend was killed by prison officers.

This is Rodney King’s letter in full:

————————————————————–

Number : HB8123 KING

HMP Full Sutton

York YO41 1PS

10.02.2004

Dear Mr. Di Stefano,

I write you regarding two separate issues. Mr. Shipman and help with appeals for against three convictions in two separate courts.

First of all, Mr. Shipman.

I don’t believe he killed himself, in fact I think prison officers killed him.

I arrived at Wakefield on 28.05.03 and was transferred here to Full Sutton on 15.08.03 after being assaulted by two of Wakefield’s SOs and being called a black c**t by one of the same prison governors, a Mr. Ryan. The two SOs are called SO Millburn and S/O Boyer.

Sir, Mr. Shipman (Fred, as I called him) arrived at Wakefield after me and we became good friends.

We attended the same H/Shop together, we went to the sports field together, we played scrabble, a card game which he told me he and his wife used to play both in my or his cell.

Harold was always a gentleman. I never saw him angry even though Wakefield’s officers were constantly giving him a hard time.

On one occasion I was called to the SOs office and questioned as to “what does you and Harold Shipman have in common”. I immediately went to Fred’s cell which was just across from mine and before I could tell Mr. Shipman what had happened, he told me that he was questioned earlier the same day regarding the same issue.

After I was repeatedly threatened by Wakefield’s officers, I started to complain and officers would tell me that before Shipman arrived, I had no problems.

A prisoner called Shepp, Harold’s next door neighbour, who I’m told used to be a nurse, cautioned me for befriending Mr. Shipman. Shepp told me that the officers were abusing me because I had made friends with the man who numerous officers were saying he had killed their family. In fact along with Shepp, other prisoners were telling me that they didn’t want any blood spilled on them when Shipman finally got done by officers.

Harold was first in the gym and last to leave. He was preparing to live, not to take his own life.

Shipman told me that after he was convicted, he became ill. When I met him he was starting to pick himself up again.

I’ll write to you separately regarding my appeals.

Sincerely yours,

Rodney King

——————————————–

In the letter, King reported an occasion when he was called to the SO’s office and questioned about his friendship with Harold Shipman.

Afterwards, when he left the office, he went straight to ‘Fred’s’ (as he called Shipman) cell to tell him what had happened.

Shipman reported he had also been asked questions by a guard earlier the same day. ‘Raised voices’ had been heard coming from Shipman’s cell when King and one other prisoner were present, said the guard. He was asked if King was bullying him.

“No”, answered Shipman. He considered King his friend and had never been bullied by him.

When asked to write about being questioned by the guard, Dr. Shipman wrote this letter.

After both Shipman and he had been questioned, King began to think that an attempt was going to be made to pass off ‘bullying’ by other prisoners as grounds for what would later be made to appear as Harold Shipman’s suicide.

King made it clear that he, and other prisoners in Wakefield Prison, believed Shipman was killed by prison officers in an act of revenge on behalf of ‘numerous prison officers who said he’d killed their family’.

Shortly after he made the claims about how he and others believed Harold Shipman really died, Rodney King could not be contacted. He has not been heard from since.

Dr. Shipman ‘died’ on January 13, 2004. Unusually, it was six months before he was cremated and his ashes scattered. Did he really commit suicide or was he murdered? The authorities certainly were not eager to investigate.

His family sought his immediate burial but forced to bow to pressure by authorities who, for unknown reasons, wanted Harold Shipman cremated. But not before sever warnings from the morticians after so long a period in a 7ft metal drawer that his body was simply ‘falling apart’.

Shipman’s arms are already coming away from his trunk, it is claimed, and a coroner contacted the family to warn that the corpse of the GP, dubbed Dr. Death for killing at least 215 elderly patients, was “deteriorating” at a rapid rate.

His son Christopher made the complaint. However, the body of the Manchester GP it can now be revealed was disturbed for two postmortems to be carried out – amid claims by his family and others that he was murdered in jail. They have also asked for independent tests.

A source said: “His arms are causing particular concern. There is a worry they could detach from the torso. The morticians and funeral directors were asked to carry out remedial work, but there is only so much you can do. Shipman’s family is very angry about it and claim the body is being pulled out of the drawer too much, affecting the temperature.”

It is somewhat ironic that what Shipman was denied at trial, the right to carry out a second post mortem on the victims, would be applied to him. But then the Authorities would always have the upper hand.

Evidence was collated and Wife Primrose, 54, and Christopher handed their evidence to prison ombudsman Stephen Shaw.

His report into the suicide has been passed to interested parties. The family are still of the belief it supports many of their claims that Shipman did not commit suicide.

The letter and evidence from inmate King who carries the name of the famous American activist was not part of the evidence presented to the Ombudsman and neither were the authorities interested at interviewing him. King has, in fact, simply ‘disappeared’ from the prison radar and cannot be found which is strange for a prisoner serving also multiple life sentences.

Shipman may have taken the truth of his death with him to the grave. But the results of the two postmortems tell a tale of considerable intrigue that do not necessarily point to suicide.

Felicity Treanor

An upcoming documentary coming soon where all will be revealed.

NB: Some images retrieved from Google, will remove at owner’s request.