Ivar Kreuger was born on the 2 March 1880 in the Swedish seaside town of Kalmar. His father helped to run a shipping business and was the local Russian Consul. Kreuger trained as an engineer in Stockholm and at the age of 20 left his homeland to pursue his fortune in America.

Vadstena, a lakeside medieval town in central Sweden, has for centuries drawn pilgrims through the surrounding cornfields to the tomb of Saint Birgitta, a 14th-century noblewoman and mystic. Five minutes’ walk from the abbey where her remains lie stands an imposing castle, surrounded by a moat, its tall Baroque tower looming through the mists that swirl off Lake Vättern.

In the cellars of this fortress are racks upon racks of cables, letters and documents, stored in plain cardboard boxes. Two kilometres of them pertain loosely to one man, Ivar Kreuger, who in his heyday had a stature far more revered—at least in the world of finance and international diplomacy—than that of his devout countrywoman, Birgitta. Occasionally his papers still lure curious visitors to Vadstena.

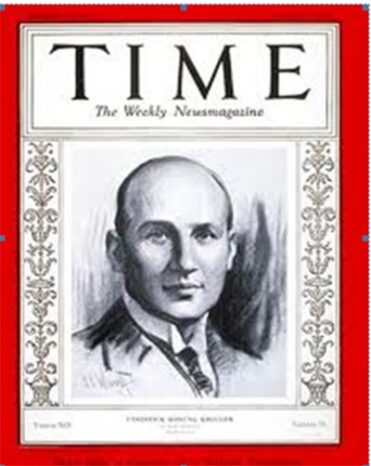

If Birgitta is the patron saint of Europe, Kreuger was the patron saint of sinners; he was arguably the most brilliant and ambitious swindler who ever lived. In the first three decades of the 20th century, he built up an industrial empire founded on the humblest of innovations, the Swedish-made safety match, that lit a fire of speculative excess around the world creating, then burning through, fortunes that would be measured now in the billions. In the words of John Kenneth Galbraith, writing in 1961:

“Boiler-room operators, peddlers of stocks in the imaginary Canadian mines, mutual-fund managers whose genius and imagination are unconstrained by integrity, as well as less exotic larcenists, should read about Kreuger. He was the Leonardo of their craft.”

This quiet man, who corresponded succinctly in many languages, could so nearly have become one of the 20th century’s greatest individuals. When he shot a bullet, with steady-handed precision, through his heart in his Paris apartment on March 12th, 1932, it felt for many as if a light had gone out across a darkening inter-war Europe and Depression-era America. His resounding optimism and his attempts to combat the era’s despair by channelling money from rich nations to impoverished ones had earned him admirers everywhere. This newspaper, writing a week after his suicide, described the tragedy as one worthy of Aeschylus or Sophocles:

“His death in Paris last Saturday by his own hand represents the veritably tragic wreck of a career which in its sphere was unsurpassed by that of any individual in living memory,” it said. Kreuger, it added grimly, in seeking to be a “force for good”, was crushed by the bleakness of his time.

So, when The Economist, three weeks later, reported that chartered accountants had discovered “deception and manipulation of accounts” in his business empire, this paper was not alone in feeling bitterly humiliated. The world threw up its hands in horror as details emerged of assets inflated by double counting and, worst of all, the forgery in Krueger’s hand of $142m of Italian bonds supposedly sold to him by Benito Mussolini’s government. In Sweden, where Kreuger had been considered a national treasure for 25 years, the suicide rate rose, and the prime minister fell. It soon became clear that Kreuger’s businesses owed more than the country’s national debt. In America shares of his international holding company collapsed, taking with them the life savings of thousands. His reputable New York underwriters, Lee, Higginson, disbanded in shame.

After the “Kreuger crash” shook Wall Street, America’s Securities Act was passed in 1933 strengthening disclosure requirements for all companies selling stock. It stemmed directly from the Kreuger experience. It took five years for investigators to disentangle the accounts of his 400 companies.

The reckoning?

In a 15-year career he was estimated to have burned through about $400m of his investors’ money.

His biographies sought to explain how a man of such genius and apparently noble aspirations destroyed so much. Today’s financial world looks rather more like the era of rootless, trans-oceanic finance that Kreuger entered when he first arrived by ship in New York in 1900, with $100 in his pocket. Kreuger’s story is a lesson in the dangers of excessive confidence, and fickle liquidity that may be as relevant today as they were in the Roaring Twenties.

Kreuger found a job as an engineer, helping build New York’s Plaza Hotel and other landmarks. He resolved to apply what he had learned about new construction techniques back home in Sweden, and in 1908, aged 28, he set up a company in Stockholm with a friend. The Kreuger & Toll partnership quickly gained a reputation as the best construction firm in Sweden, built the country’s first skyscraper and went public in 1914. But by then, Kreuger’s restless mind was absorbed with another venture, which, though so rudimentary compared with engineering, he intuitively sensed had grander scope.

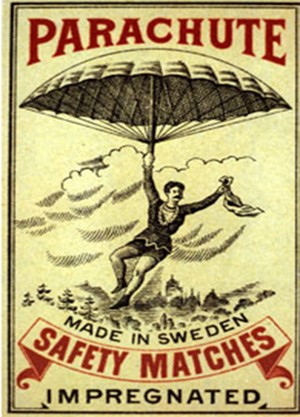

Backed by a trio of Sweden’s top banks, he took over his father’s match business, and hoodwinked his uncle, who was drunk at the time, to let go of his British match interests. When the outbreak of the First World War restricted the supply of aspen and chemicals used in Swedish matches, Kreuger found an opportunity to outflank Sweden’s biggest producer and force it into a reverse takeover. By 1917 Kreuger was done with construction engineering; he founded the Swedish Match Company and his reign as one of the world’s great monopolists—and financial engineers—began in earnest.

Just over a decade later in 1928, The Economist, writing of Swedish Match, noted: “It is curious that of the great international trusts in the industrial world there is none more firmly established than the colossus that has been built on matchsticks.” But the humble matchstick is not as puny as it sounds; indeed, the ability to cup flame in the hand, rather than rubbing sticks together for hours, must count as one of the greatest innovations of all time. After the war, its use spread around the world with gas ovens and cigarettes. A letter written by Kreuger to a friend in 1931 reveals his profound faith in his product’s ability to hold its own in good times and bad. Swedish Match, he confided, had “not felt any effect of the present crisis…Often great unemployment causes an increase in the consumption of matches because people seem to smoke more cigarettes when they are not working.”

Matchmaking, however, is a fairly rudimentary business, and in post-war Europe, it took very little capital to run small, inefficient match factories that made just enough money to survive. Krueger’s vision was to consolidate them, and he did so in a way that brilliantly served a dual purpose: making him immensely rich and powerful on the one hand and helping recapitalise Europe’s shattered post-war economies on the other.

After secretly acquiring factories around Europe during the years of post-war Depression in the early 1920s, from 1925 onwards Kreuger began offering a bargain to penniless governments that many found hard to refuse. Kreuger would, he said (usually with great secrecy); lend money to countries that provided him with a national monopoly on match production. His monopoly and skilled marketing would increase sales (Kreuger was a first-rate salesman, too: he is said to have propagated the myth that it is unlucky to light three cigarettes from the same match).

Governments taxed matches, so the higher sales would raise tax revenues used to repay the loans. It was, boasted Kreuger, an almost fool proof business plan: the loans were secured against revenues that he controlled; the monopolies, meanwhile, ensured generous returns.

According to a 1930 article in Foreign Affairs, Swedish Match struck such deals with nine European states and three South American countries in the 1920s. The loans totalled $253m, a fortune at the time. Germany received $125m; France, which never granted a full monopoly, $75m. In 1930 Kreuger even sent an emissary from his New York broker, Lee, Higginson, to China to persuade the Chiang Kai-shek government to give it a monopoly. The response was positive; the finance minister, Krueger’s envoy wrote, “is one of the few Chinese with whom one can feel an accurate interchange of ideas is possible.” The country was at war over Manchuria, however, and Kreuger doubted the Nationalists’ ability to guarantee a monopoly. He called the talks off.

From the outset, the monopoly-for-loans quid pro quo enabled Kreuger to portray himself less as a naked profiteer (he was obsessed with maintaining “stable” i.e., high, match prices) and more as a statesman, with the interests of European political and economic stability at heart. When much of Europe was starved of capital and balkanised after the Versailles peace treaty, he looked like a one-man Marshall Plan. Many of his loans were put to good use; he helped Germany, for example, to pay its war debts; he then mediated at the 1930 reparations talks between France and Germany. He could have accomplished none of it, however, without identifying another golden opportunity in that lop-sided era: the surplus capital in America and the greedy speculative spirit that accompanied it.

As Foreign Affairs put it in 1930, “the world war enriched America and impoverished Europe.” America’s government was loath to finance the reconstruction of the Old Continent, but on Wall Street, when Kreuger came knocking, the doors swung wide open. In 1923 he set up the International Match Company (IMCO) in New York, and in less than ten years he raised an estimated $150m from American investors. All but $4.5m of that was transferred abroad, to finance government loans and expansion of the match empire. He hooked investors with an intoxicating cocktail of rising dividends and tax-exempt foreign earnings.

But despite the apparently flawless business model, match monopolies, it turned out were not all that profitable. In order to offer spectacular returns, Kreuger paid dividends out of capital, not earnings. He was, in effect, operating a giant pyramid scheme, reliant on confidence to maintain a steady inflow of cash.

He rewarded their faith handsomely; the stock market value of IMCO rose, according to Foreign Affairs, by 1,100% between 1923 and 1930. Even during the stock market crash of 1929, there was a mere hiccough before prices sailed higher. In 1931 a New York Times advertisement stored in the castle at Vadstena summoned investors to take part in an IMCO issue of $50m 5% convertible gold debentures. By then, it says, the company controlled 250 factories in 43 countries, many of which were operated under government-granted exclusivity. The resources, it said, were to expand capacity in Poland, as well as buying German, Turkish and other government bonds. The match business, it averred, by and large had “not suffered from the general business depression”.

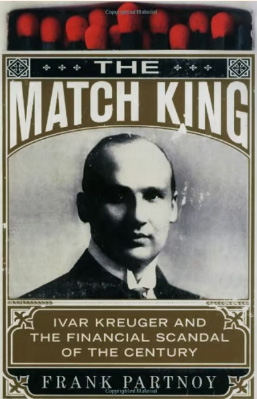

The dazzling chutzpah with which Kreuger wheedled money out of American and other speculators was especially evident in the way he handled his companies’ finances. It is here, perhaps, that Krueger’s misdirected genius finds its most powerful resonance today. A book “The Match King” by Frank Partnoy, professor of law at the University of San Diego, will argue that the line of many of today’s most dazzling financial innovations can be traced directly back to Kreuger.

Long before modern financiers created a market in asset-backed securities Kreuger was a master of the art. Effectively, the securities he sold to investors provided loans for governments secured against assets that he himself controlled. The assets were held offshore, which today’s tax planners would welcome, and mostly off-balance sheet, the custom at Enron and many of the banks that have suffered this year. He invented the activist investor’s dream of being able to control a company’s destiny without owning it, by separating A shares from B shares (a practice until recently still common in Sweden). That enabled him to control a $600m empire with ownership of just 1% of the shares. He wrote the book on mystifying Enron-style accounting practices: when Foreign Affairs took a bold stab at exploring his accounts in 1930, it said the value of combined assets of all his companies was estimated at $630m. Of that, only $200m were match-related; another $400m were simply lumped together as “other investments” (it had $30m in the bank).

Like other free-wheeling entrepreneurs, Kreuger did not disguise his contempt for accounting norms. In a rare interview in 1929, he told Isaac Marcosson of New York’s influential Saturday Evening Post that the key to his success was “silence, more silence, and even more silence”. (In a sycophantic letter to him found in Vadstena, Marcosson writes, “I regard it as a great privilege to be your Boswell.”) Secrecy, and his extensive network of paid informers around Europe, served him well; not only did it keep investors in the dark, but also enabled him to do deals with rival governments, such as republican France and fascist Italy, who loathed each other.

Yet amidst the telegrams and letters bundled in boxes in Vadstena, evidence of a growing concern about his affairs emerges after 1929 that suggests a cataclysm is in the making. By late 1931 Kreuger is, for the first time, unable to provide a colleague with a definite assurance on IMCO’s dividend payments—the bedrock of the company’s allure. A yellowing letter with frayed edges from one of his brokers at Lee, Higginson that year advises him, in unfailingly polite terms, that a couple of his bank creditors “insist that they are not as completely informed about the company as they should be”.

Apologising for the imposition, his correspondent relays their request for what is meant in his accounts by “real-estate investments outside Sweden” and “other industrial shares”. In an eerie precursor of today’s concerns about American subprime mortgages, he is asked to explain, too, what he means by “loans secured by real-estate mortgages”. Kreuger replies curtly that he is “greatly disappointed” by the attitude of the banks.

Krueger’s luck was running out, and his unswerving confidence was beginning to look like a con-man’s desperate manoeuvring. Short sellers were targeting his companies. Though he remained outwardly composed, a jotting on a cable reveals his private fears. “There is at present a bear attack going on and it is very important.”

The end, when it came, was quick. Desperate to keep his creditors at bay, he sought to arrange the merger of one of his companies, the Ericsson telecoms group, with America’s International Telephone & Telegraph. With his back against the wall, he acceded to IT&T’s request for an audit: they discovered a hole in his accounts.

In Sweden he was bailed out at the eleventh hour by a government which realised the economy was at risk from a Kreuger crash. But by this stage, he was promising as collateral assets that he had already pledged to others. A few creditors and colleagues believed there was one secret card remaining up his sleeve; the Italian government bonds he had locked in his safe in Stockholm.

Only Kreuger knew that he had personally falsified the signatures on the bonds. When it looked as though there was no alternative to owning up to the forgery, Kreuger walked to a gun-shop and bought a 9mm automatic pistol. That night, the man who had never married, who kissed women on the wrist rather than the hand for fear of germs, had a last tryst with a young Finnish girlfriend. The next day, lying on his bed in a pin-stripe suit, he shot himself, blowing out the last flicker of illusion in a hopeless age.

Unravelling the web of his complex business took some time and it was several months before the financial world realized that it had been taken for a ride which had cost it a fortune. Of the $148.5 million paid over by American investors, $144 million had disappeared into Krueger’s own accounts in Switzerland and Liechtenstein where still today a substantial part is still held and unaccounted.

First Published 2013

©GDistefano/CABayford – 2013

NB: Some images retrieved from Google, will remove at owner’s request.