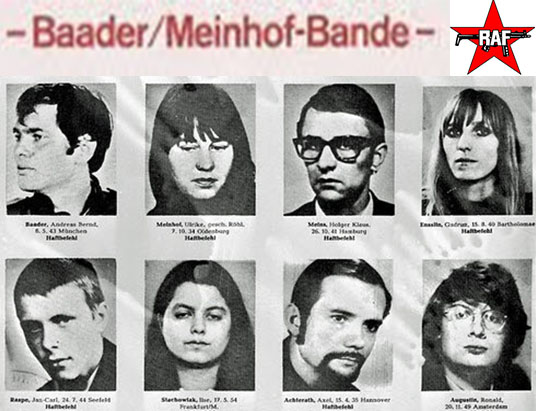

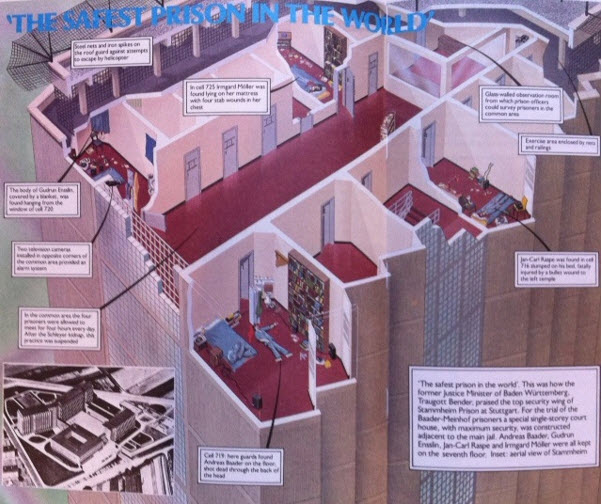

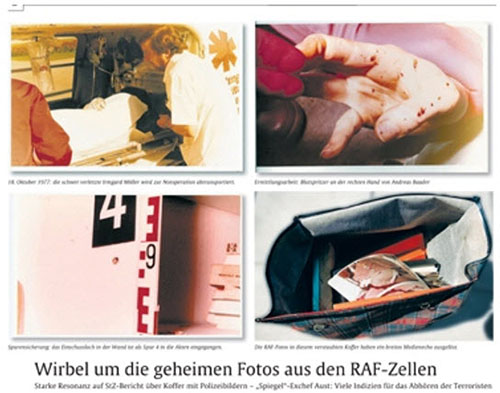

Tuesday, 18 October 1977, began as a routine day at Stammheim Prison in Stuttgart, West Germany. Two officials were taking breakfast, coffee, boiled eggs, and toast, to the seventh-floor cell. At 07.41am they opened the door to cell 716, to find the ‘terrorist’ Jan-Carl Raspe propped up on the bed and bleeding from a wound on his temple. The guards shut the door and alerted the prison hospital, and Governor. When the cell was re-opened, a 0mm calibre pistol was found next to Raspe, who died in hospital three hours later. In cell 719, Andreas Baader was found dead in a pool of blood with a gun at his side, while across the corridor, in cell 720, Gudrun Ensslin was discovered hanging from a bar across her cell window. In cell 725, the fourth prisoner, Irmgard Moller, was found lying on her bed, badly injured with four stab wounds in her chest and a butter knife by her side; after emergency surgery, she survived.

At a press conference, later that day, the Minister of Justice Traugott Bender gave the official verdict on the deaths as suicide, even though no evidence had yet been received from forensic scientists. Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, called for a full investigation into the deaths in order to establish how the weapons had been smuggled into the jail, how they had remained hidden despite the highest security measures, and, how the prisoners had managed to communicate with each other in order to keep to a suicide pact, taking into consideration they were supposed to be kept in total isolation at that time. The only certainty was that the Baader-Meinhof gang had died as they had lived: – secretly and bloodily.

The origins of the Baader-Meinhof gang can be traced back to the student protests of the late sixties when demonstrations were staged to oppose the support for the War in Vietnam in particular, and capitalism in general. In 1968, an incident occurred that deemed many pacifist demonstrators towards more violent forms of protest. During a large demonstration against the Shah of Iran’s visit to Berlin, a young student named Benno Ohnesorg was shot dead by a policeman. It provoked a great outcry. Leftist journalist, Ulrike Meinhof, wrote that Ohnesorg was the ‘victim of SS mentality and practice’ and, peace campaigner.

Gudrun Ensslin, told the Socialist German Students Union (SDS), the day after the shooting, that a ‘Fascist State’ was emerging in West Germany that was ‘out to kill us all, and, that they could only answer this sort of violence with violence. The tall, striking blonde, with a thin pale face, and black eyeliner, who addressed the SDS with her impassioned words was born in 1940, in a tiny village north of Stuttgart, the daughter of a free-thinking Pastor. She had worked hard at school, helped her mother at home, taken Bible classes and trained to be a teacher. In 1965 she went to the Free University in Berlin, where she became involved in anti-Vietnam protests. In 1967, she met the swarthy, blue-eyed Baader and was dubbed ‘his true revolutionary bride.’

Andreas Baader was born in Munich 1943, the son of a historian who was killed during the Second World War. Doted on by his mother, he was an obstinate child, who was an academic failure at school and drifted to Berlin where he dabbled in art and journalism, he lived off a wealthy painter and his own good looks. He had a taste for glamour and flashy cars and was easily coerced by the strong-minded Ensslin into the world of the urban guerrilla.

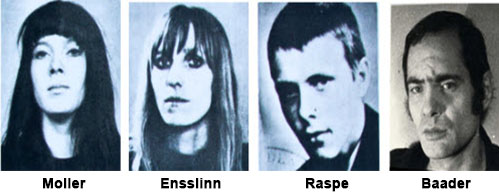

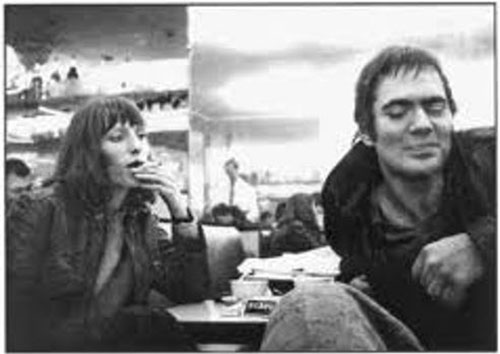

Ulrike Meinhof (Top) Gudrun Ensslin In 1965 Pornographic Film

Ulrike Meinhof (Top) Gudrun Ensslin In 1965 Pornographic Film

Dressed in the revolutionary chic black sweaters and jeans, Baader and Ensslin entered a department store in Frankfurt, in April 1968, and planted fire-bombs, one of them in a piece of ‘Old German’ reproduction furniture. No one was injured but the couple was arrested and sentenced to three years in jail. Ensslin stated “We don’t care about burnt mattresses. We are worried about burnt children in Vietnam.” The two were released in 1969 pending an appeal and welcomed by the radical Left as heroes. When their appeal was rejected, Baader and Ensslin went into hiding and escaped to Switzerland, remaining there until they thought it safe to return to Germany. In April 1970 Baader was arrested in a Berlin roadblock and sent to Tegel Prison in Berlin.

Arrest Of Baader in April 1970

Arrest Of Baader in April 1970

In jail, Baader received visits from Ulrike Meinhof who had written in an article at the time of the Frankfurt arson trial: ‘It is better to burn a department store than to run one.’ Meinhof was the daughter of an art historian and was born in 1934, in north Germany. She was orphaned as a young teenager and raised by Renate Riemeck a professor and co-founder of the German Peace Union. She was a studious, idealistic girl, interested in art and music; she was also articulate, daring, and liked to lead, though she also liked to belong to an elite. As a student, she edited a pamphlet called ‘Das Argument’ working hard for the anti-bomb campaign,

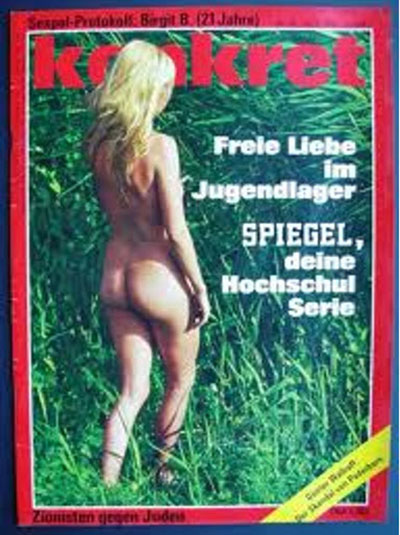

In the late Fifties, Meinhof met Klaus Rainer Rohl, editor of the radical newspaper Konkret, which she began writing for in 1959, and later worked as foreign editor and editor in chief, making a name for herself as an outspoken political columnist. She also married Rohl.

By 1964, Konkret was in severe financial trouble as the funding from East Germany dried up. To boost sales, Rohl turned it into a ‘porn with politics’ paper that featured extracts from Swedish pornographic novels.

It worked! The Rohls entered the fashionable society of the chic Left, materially secure. and publicly successful. Meinhof, fashionably dressed and with her hair styled, appeared on television and radio, speaking out for the poor and less well to do. When her marriage broke up in 1967, she moved to Berlin, leaving behind her fur coats and violin, and became a part-time lecturer at the Free University. Her writings showed increasing sympathy with the Left and her home became a meeting place for radicals. It was at this time that she met a quiet young man called Jan-Carl Raspe. He was the son of a chemical factory director, who had died when the child was young.

Brought up by his mother, he became a sociologist and wrote a book on bringing up children. In Berlin, he became involved in the anti-bomb student protests, turning to more active political protests after the shooting of Benno Ohnesorg.

Meinhof’s relationship with Baader and Ensslin, both of whom she had interviewed during the Frankfurt trial, was cemented too. Her movie style rescue of Baader in 1970 was her initiation into the terrorist elite.

Shortly after Baaders re-arrest and imprisonment that year, Meinhof arranged to assist him with research for a book he claimed to be writing, and for which he was allowed out of prison to study in a university library. As the two ‘researchers’ sat quietly talking at a table, two young women wearing wigs and carrying briefcases entered. Minutes later, a masked man with a gun rushed in and the two women produced pistols from their bags. In the gunfire that followed, even though most of it was at the floor, a librarian was badly wounded. Meinhof and Baader leaped dramatically from the library window and escaped in a silver-grey Alfa Romeo, driven by the young recruit Astrid Proll.

Along with lawyer Horst Mahler, Baader, Meinhof, and Ensslin chose to call their movement the Red Army Faction (Rote Armee Fraktion) after the Japanese Red Army and flew to Jordan to be trained by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). They made contacts for funding and weapons, and at home set up safe houses and communications network to back up their operations.

Bank raids were carried out to finance the movement. Their activities required stolen cars, false documents, disguises, and electronic devices, as well as weapons.

The Red Army Faction (RAF) began its real campaign in May 1972. In a protest against American intervention in Vietnam, the RAF planted bombs at the headquarters of the US Fifth Army Corps in Frankfurt, killing an American Colonel and injuring thirteen others. Two weeks later, bombs killed three and wounded five at an American base in Heidelberg. Other bomb attacks were launched at police stations and at Axel Springer Press building in Hamburg.

On the 13 May 1972 Mi6 open a file on the RAF.

In June 1972 after a tip-off, Baader, Raspe and Holger Meins, were arrested in a massive police raid and shoot out at an arms’ hide out in a Frankfurt garage, after the three drove up in a lilac Porsche. Baader was shot in the thigh. A week later, Gudrun Ensslin walked into a boutique in Hamburg and carelessly left her leather jacket on a sofa while she tried on some sweaters. An observant shop assistant picked up the coat and, noticing it was unusually heavy, felt in the pocket to find a pistol. Alerting the police, she delayed Ensslin until the police arrived. A second gun and newspaper cuttings on Baaders’ arrest was also found in her bag. Before the month was out, another tip-off this time by a Leftist who believed the terrorist gangs were harming the Left, led police to Ulrike Meinhof. In her luggage, they found three pistols, one sub-machine gun, two hand grenades, a ten-pound bomb, and a coded letter from Ensslin.

The authorities had succeeded in rounding up and imprisoning the main ringleaders of the Baader-Meinhoff gang and they were later incarcerated in the specially built, top security Stammheim Prison at Stuttgart. Their trial did not begin until 1975; it took place in a special courthouse adjacent to Stammheim Prison at Stuttgart, lasted nearly two years and was the focus of many legal wrangles. As the RAF began its bloody campaign to have its leaders released, other groups sprang up, sometimes working with them; one of these was The Second of June Movement, named after the date on which Benno Ohnesorg was shot. As terrorist raids became more widespread and murderous, a wave of alarm spread through Germany and the Federal Government began tightening up security. The necessity for this was further highlighted later in 1972, with the massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics. The Munich terrorists demands included the release of Baader and Meinhof. The demands were not met and, after a shoot-out with police, all the hostages were killed.

Subsequently, special anti-terrorist squads were set up, including the GSG9 a highly trained, mobile force that was to make its dramatic debut at Mogadishu in 1977.

In 1974, Holger Meins died in prison from a hunger strike and a number of arrests were made in the demonstrations that followed. A week later, the President of the West German Supreme Court, Gunter von Drenkmann, was shot dead on his 64th birthday. In February 1975, the Second of June Movement kidnapped political leader Peter Lorenz and achieved its aim in exchanging their hostage for a number of prisoners, some of them from the Baader Meinhof gang.

Holger Meins Arrested

Holger Meins Arrested

In May 1976, violent riots broke out in several German cities after the death in Stammheim prison of Ulrike Meinhof, who had been sentenced to eight years in prison for her part in the Baader’ s rescue. Many factions refused to believe the official version, that she had hanged herself, and conflicting evidence that emerged fuelled the belief that she was murdered.

Ulrike Meinhof’s Body After She Was Found Hanged In Her Cell

Ulrike Meinhof’s Body After She Was Found Hanged In Her Cell

Several days before the end of the Stammheim trial, a group of motorcycle-riding terrorists pulled up alongside the car of Siegfried Buback, West Germany’s Chief Public Prosecutor and shot him dead. In April 1977, Baader, Ensslin and Raspe were given life sentences for the murders of four American soldiers in the army base bombings and 34 attempted murders, plus fifteen years for bombing two police stations, a publishing house, a Judge’s car, and for the attempted murder of policemen during the shoot-out in which Baader and Raspe were arrested. In July terrorists killed Jurgen Ponto, head of a large German bank. The demand for the release of the imprisoned terrorists was repeated, along with threats of further violence.

No amount of security measures seemed to deter the Baader-Meinhof supporters in Cologne and, on 5 September 1977, they kidnapped the powerful industrialist Hans Martin Schleyer.

Then, on the 13 October, they hijacked a Boeing 737 and flew it to Mogadishu, where the aircraft and its 82 passengers were dramatically rescued by the GSG-9 anti-terrorist squad. This was a famous victory, that produced a general feeling of relief that, at last, something was being done to combat terrorism. Hardly had the congratulations subsided when the news of the Stammheim deaths on 18 October was released. Schleyer’s fate was sealed: he was found dead the next day.

The official explanation, for the events at Stammheim that night, was that the terrorists hope of being released were blown away when the hijackers at Mogadishu were defeated and this, with the government’s refusal to give in to the demands made by Schleyer’s kidnappers, compelled the four to carry out a suicide pact in their despair. Twelve hours before his death, Baader is reported to have requested a meeting with a government official at which he had seemed confident of his imminent release from jail, threatening that, if the Mogadishu hijacking failed, then Germany could expect an immediate ‘major blow.’ This could be taken as a reference to the suicide pact that would leave the government with the problem of explaining the terrorist’s deaths. Government officials immediately claimed that the suicide pact had been deliberately made to look like murder.

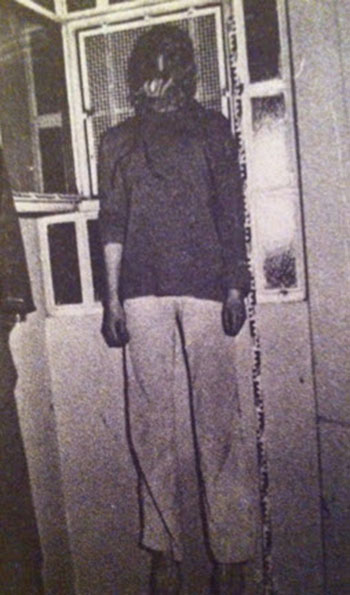

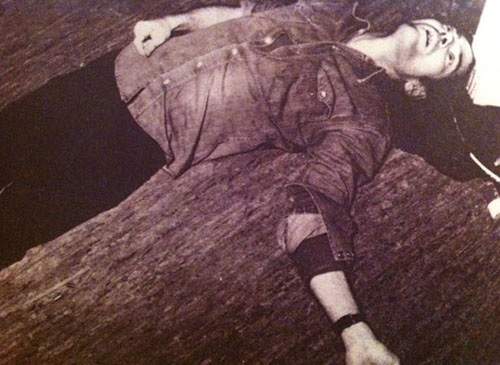

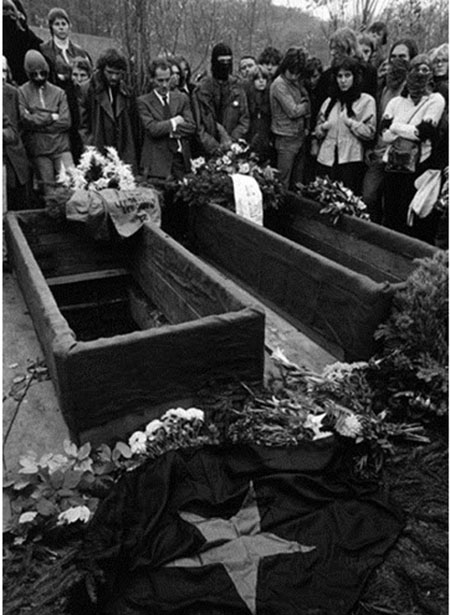

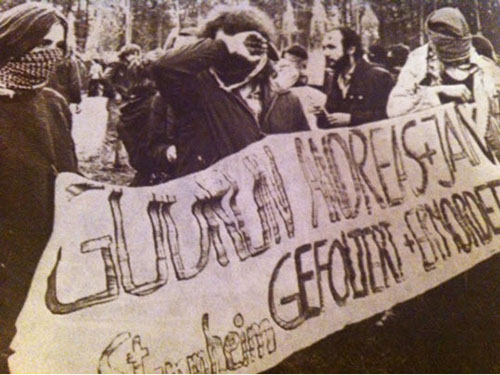

EXCLUSIVE: Gudrun Ensslin Found Hanging In Her Cell

EXCLUSIVE: Gudrun Ensslin Found Hanging In Her Cell

As the facts about the Stammheim deaths began to emerge, the very nature of the prisoner’s injuries raised doubts as to whether they could have been self-inflicted. As for a motive for their murder, it had become apparent by the summer of 1977, that as long as these particular terrorists were in jail, their supporters would have a motive for kidnapping, hijacking, and increased violence, in their bid to secure the prisoners’ release. Much of the urban guerrilla activity during the ring-leaders imprisonment had been geared towards this aim. The German government desperately needed to break the terrorist grip on the country; the killings of Drenkmann, Buback, and Ponto, Schleyer’s kidnap and murder, and the Mogadishu hijacking strengthened their resolve. A convenient way of erasing the terrorists’ motivation would have been to simply ‘remove’ their leaders.

EXCLUSIVE: Jan-Carl Raspe Died Three Hours After Being Found With Bullet In Head

EXCLUSIVE: Jan-Carl Raspe Died Three Hours After Being Found With Bullet In Head

Hundreds of police and criminal investigators were employed on the Stammheim case. Internationally recognised doctors gave expert opinions and a parliamentary committee from Baden-Wurttemberg conducted its own investigation. Six months later, in April 1978, the Stuttgart public prosecutor dismissed the preliminary proceedings, upholding the official verdict as suicide. This ignored contradictions in scientific and medical evidence and, the fact that, despite allegations, the possibility of murder had never been investigated. The hearing was given the official title of ‘Investigation Into The Suspected Attempted And Successful Suicides.’ Chief criminal lawyer Gunter Textor, leading the Stammheim special commission, said that “violence by a third party was out of the question because, in such a secure institution as Stammheim, it would be impossible.”

Baader, Ensslin, and Raspe, had all been imprisoned on the seventh floor of the prison. They had been joined there in January 1977 by Irmgard Moller, who was charged with taking part in the Heidelberg bomb attack in 1972.

Since the kidnapping of Schleyer, the four were supposed to have been kept in total isolation, according to a special law that had been passed.

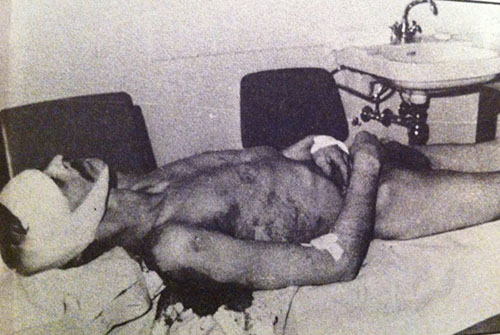

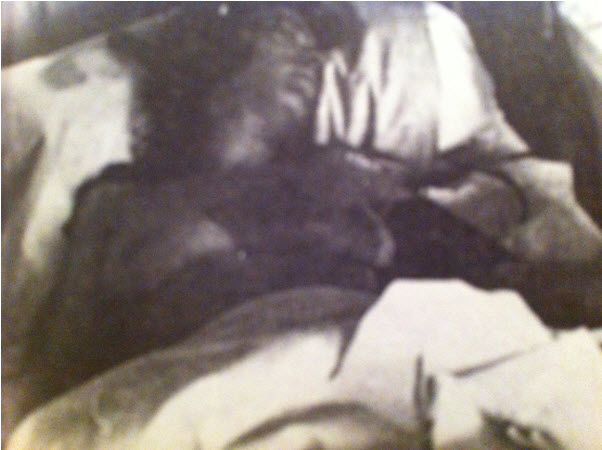

EXCLUSIVE: Andreas Baader Laying In Pool Of Blood With Bullet Through His Brain

EXCLUSIVE: Andreas Baader Laying In Pool Of Blood With Bullet Through His Brain

They were not supposed to receive any newspapers, letters, news bulletins on radio or television, were not allowed to communicate with one another, and their meetings with lawyers were conducted under strict security. A meticulous search of each cell was supposed to have taken place twice daily and the wires linking each cell to the prison radio service were supposed to have been disconnected so, that the gang would not be able to receive news of the Schleyer kidnap.

An official report later claimed the prisoners re-connected their radio systems and communicated with each other, using the radio wiring. Raspe, it was claimed, communicated via his razor connection.

He had been studying electronics in prison.

The police also claimed that the terrorists had used their record player loudspeakers to make contact with each other in Morse code, but their record players were supposed to have been confiscated during the tightening-up procedures after the kidnapping. It was also claimed that Baader, Ensslin, and Moller, had concealed headphones in order to hear the prison radio, but only Mollers’ was ever produced to substantiate these claims.

EXCLUSIVE: Only Survivor Irmgard Moller With Stab Wounds To Her Breasts

EXCLUSIVE: Only Survivor Irmgard Moller With Stab Wounds To Her Breasts

Even the exact time of deaths was never accurately established.

Pathologists had been unable to begin the autopsy until 4pm on the 18 October, because they had to wait for the arrival of lawyers and representatives of the public prosecutor’s office. The most accurate estimate was that Baaders’ death had occurred sometime between 12.15am and 2.15am, and Ensslin between 1.15am and 1.25am, but when experts were asked whether the deaths could have occurred as late as 6 am, the answer was ‘YES!’

Baader had been found lying on the floor, his eyes open, with his head and a pistol in a pool of blood. Near his knee were two spent cartridge cases.

His was perhaps the most difficult to explain. After a post mortem, experts arrived at the following conclusions:

Baader was killed by a single shot that entered at the back of his neck (at the base of the skull) and exited on the other side of his skull, just above the hairline.

They also said that the barrel of the gun must have been placed directly against the base of the skull. In addition, forensic scientists found traces of blood on the palm and thumb of the right hand. These findings were reported at the hearing and it was accepted by the public prosecutor that Baader, who was left-handed, had held his pistol pointing upwards in his right hand, pressed it to the base of his skull and pulled the trigger with his left thumb. After the shot, blood had spattered onto his right hand.

However, the criminal police special commission had discovered that the cartridge case from the death bullet lay to the right of the corpse. Baader’s weapon, a 7.65mm calibre pistol, was of the type that ejected the cartridges to the right.

The criminal police thus, deduced that Baader had held the pistol pointing downwards and, directing the barrel at the base of his skull with his left hand, had pulled the trigger with his right hand. This is the only way that the position of the cartridge can be explained.

This does not, however, explain why the blood stains were found on his right hand and not on his left.

One important piece of evidence remained concealed from both the German and foreign forensic scientists together with the parliamentary investigation committee, which concluded its work on 21 February with the verdict as suicide.

MI6 had been covertly intercepting communications of both the Baader-Meinhof gang and the East and West German Government. The highly secret operation in such interceptions was to ensure that no German leader as Adolf Hitler could ever be elected in Germany again and using such, and up until 1998, regularly intercepted communications including postal letters.

On the 21 February, a ballistic report was filed with the public prosecutor’s office in Stuttgart. The ballistic expert, Dr. Roland Hoffman, had investigated the entrance hole of the bullet at the base of Baader’s skull with gunpowder tests. Tests show, by deposits of lead and barium, the distance from which a shot had been fired: the more gunpowder deposits, the nearer the weapon was to its target. When tests were carried out using Baaders’ pistol and the ammunition used in Stammheim it was demonstrated that, on comparison, the deadly bullet must have been fired from a distance of between 12 and 16 inches (30 and 40 centimetres). Despite this discovery, the testimony of Dr. Hoffman was veiled in ambiguity. Even though he had uncovered all the signs of violence by a third party, Hoffman testified that the powder deposits on Baader’s skin must have evaporated. A shot with so few traces of gunpowder could be explained only by the presence of a silencer on the gun. No silencer was found in Baader’s cell.

The distance from which the shot had been fired was ignored by the Stuttgart public prosecutor Rainer Christ, on 18 April, when he dismissed the preliminary hearing. Rainer Christ did not clear up a further bone of contention between criminologists and forensic scientists namely, that three bullets had been found in Baader’s cell. One was embedded in the mattress, one in the wall near the window, and the third, the one that had killed him, was to the right of the corpse, in front of the bed.

Rainer Christ had at all material times been an MI6 agent.

A factor that had escaped the various committees established to investigate the mysterious deaths is that, on the 4th October 1977, a technician from the Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Bfv) places audio bugs into seven cells of which the cells on the seventh floor are included. On the 7th October, the audio capacity is enhanced and optimised using technical assistance from MI6.

The audio tapes of what happened that night have never been played but, in any case, Stammheim Prison was intercepted by GCHQ and the frequencies of the ‘audio bugs’ in the terrorist cells were known to the MI6 technical assistance.

A European Commission enquiry reaches no conclusion.

The only remaining survivor, Irmgard Möller, spoke before her sentence hearing of ‘Murder’ and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

The German police asserted that, in order to simulate a fight, Baader had first fired at the bed, then from a sitting position on the floor, shot at the wall opposite him, before shooting himself. In a police report called ‘Evaluation of the Evidence,’ the death shot was described thus: “Having passed through the skull, the bullet lost speed and landed not far from the corpse.” That document is contained in the Mi6 files on the Baader Meinhof gang.

The forensic scientists had discovered something else in Baader’s cell. Near the bullet in the wall they found a trace of ‘tissue or blood’ and concluded that, after leaving Baader’s skull, the bullet had ricocheted off the opposite wall and landed in the vicinity of the body, between it and the bed.

This evidence was not disclosed to anyone ever at any stage.

The forensic report is in the MI6 files on the Baader Meinhof gang.

Cell 719 At Stammheim Prison Where Ulike Meinhof Was Found Dead 9 May 1976

Cell 719 At Stammheim Prison Where Ulike Meinhof Was Found Dead 9 May 1976

Neither was Raspe’s death as clear cut as it was made out to be. A bullet had entered his head at the right temple, and exited at the left. It then lodged in the bookshelves. In his summation Reiner Christ claimed: “Raspe must have fired the shot from the pistol that was found near him while in a sitting position, because of the way he was laying on his mattress when he was discovered. The pistol was lying near his right hand.”

Two of the four prison officers who found Raspe that morning bleeding to death in his cell had clearly seen the weapon in his right hand.

Whether the weapon was near or in the victim’s hand was a crucial point. Professor Sellier from Bonn wrote: “If the weapon is still in the hand of the dead man it immediately indicates murder because after the shot has been fired the victim loses consciousness and the weapon falls from his hand. In the case of suicide, the weapon always lies near the body.”

The most important witness on this point was Prison Inspector Erich Gotz. On the morning of 18 October, he entered the cell with two sanitary officers, picked up Raspe’ s pistol in a handkerchief, wrapped a tea towel around it and gave it to one of his colleagues for safe keeping.

A few hours later Gotz made this statement to the police: “His right hand, which grasped the butt of the pistol, lay next to his right thigh on the bed. The back of his hand was facing upwards.”

Three other officials made similar statements. Prosecutor Reiner Christ accepted this testimony. For him, it was confirmed by something else the forensic experts said before the parliamentary committee. Professor Gartmann reported: “Anyone who had wanted to shoot Raspe while he was sitting on his bed would have had to stand behind the bed, between it and the wall. The gap between bed and wall is extremely narrow.” Professor Rauschke seconded him.

Diagrams of Raspe’s cell, however, suggest that there was plenty of room between the bed and the wall.

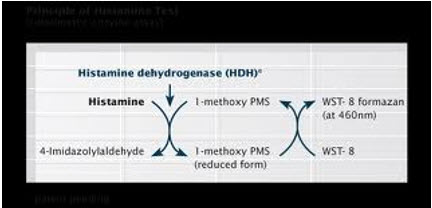

Much of the evidence in Gudrun Ensslin’s cell was ignored also. A simple test would have determined whether she died by her own hand or not the so-called histamine test.

The tissue hormone histamine always collects around the strangulation marks when a person commits suicide by hanging. If a person who is already dead is strung up to simulate suicide by hanging, the histamine will not be present.

This test was not carried out “officially” nor was the chair supposedly used in the suicide ever properly examined. The reality was that a histamine test was indeed carried out and the results “shared” with Mi6. No histamine was present.

When Ensslin’s corpse was taken down from the window something happened that was not reported to anyone but the audio bugs recorded the noise and those recordings are in the Baader Meinhof file at Mi6.

The noose broke!

The public prosecutor maintains that it held while Ensslin, who weighed 7 stones 6 pounds (48kg), jumped off the chair. Experts maintained that it held while the body was writhing in the throes of death.

Yet it broke when there was less pressure upon it.

It was never discovered whether the wire was worn or, as Ensslin’s sister Christiane suspects “perhaps only strong enough to support the weight of someone who was already dead or unconscious.”

It also remains unclear whether the chair was in the same position which the forensic scientists found it on the afternoon of 18 October as at the time of Ensslin’ s death.

Irmgard Moller was the one survivor out of the four prisoners. The public prosecutor stated that “the prisoner stabbed herself four times in the left breast with her breakfast knife. Two of the wounds were about one and a half inches deep. The deepest wounds were “very nearly deep enough to penetrate the heart and cause fatal bleeding. Not much more pressure would have been required to ensure death.” Prosecutor Christ explained Moller’s wounds as an attempted suicide because “a third party bent on murder would not have stopped short of penetrating her heart.”

Ingrid Schubert was also an original member of the Baader Meinhof gang and in a similar manner was found hanged in her cell in Munich’s Stadelheim Prison on 5 November 1977. She had been jailed in 1971, and explosives had been found in her cell at Stammheim Prison so she was transferred to Munich.

There are so many unexplained deaths of the Baader Meinhof clan.

The Prosecutor’s version of events regarding Moller does not tie in with the evidence of Professor Hans-Ebergard Hoffmeister, who operated on Moller on the 18 October 1977 in the University Hospital of Tubingen. Hoffmeister established that one of the wounds in Moller’s chest penetrated nearly 7 centimeters. The knife blade itself was not much longer at 9 centimeters. This deep wound-induced blood to flow into the fatty tissue directly encasing the heart. The stab wound must have been delivered with considerable force because a notch 5 millimeters wide and 3 millimeters deep was found in the cartilaginous part of the fifth rib.

The wounds would have been difficult to inflict as the butter knife had a rounded end and a serrated edge.

Irmgard Moller later recalled that she woke up at about 5 am on the 18 October to hear “two soft popping noises” and then a “quiet squeaking sound.” She claimed to have heard a voice saying: “Baader and Ensslin are already dead.” She recalled a “Whirling feeling” in her head and then woke up in the hospital.

On the 19 December, 1977 Moller brought criminal charges “against an unknown person for suspicion of attempted murder.”

Testifying at a January hearing the following year she denied that there had been a suicide pact. “We discussed suicide extensively after Ulrike Meinhof’s death but we came to the conclusion that suicide was not part of the Red Army Faction’s politics.”

She also denied that the four had been able to communicate with one another during the hijacking period. She admitted that she had been able to listen to the prison broadcast on the night of 17 October but that had ended at 11 pm an hour before the first reports of the rescue at Mogadishu were even broadcast.

Her ninety-minute appearance at the hearing ended with her being dragged out of court by two guards when she tried to confer with her two defence lawyers. On the 18 April 1978 her investigation was joined together with the hearing into the deaths of Baader, Ensslin, and Raspe, though in those cases no mention of murder was ever made.

In 1979 Moller was jailed for life.

Because the authorities had ruled out murder from the beginning the question of whether a so-called ‘killer commando unit’ could have broken into the ‘safest prison in the world’ was not considered.

Yet at Stammheim explosives, guns and other instruments were found and deaths by hanging of notorious inmates never properly examined.

On the seventh floor with its extra security precautions, the idea of murder was unthinkable. But the security system was nowhere near as secure as made out.

In particular, two video cameras trained on the communal area outside the cells of the deceased were found to be faulty and not operational that night.

So what really happened in the case of Andreas Baader?

The clue can be found in the “traces of sand found on his shoes at the time of death.” The German Government had decided to use Baader to negotiate the release of those on the Mogadishu flight. Baader had been taken out of the prison and flown to Mogadishu on the 17 October to trick the Palestinian hijackers of the B737 into believing that the German Government wanted to exchange the hostages on the aircraft and the kidnapped industrialist Hans-Martin Schleyer for the RAF prisoner. He was there and he was the living proof. But instead the aircraft had been stormed catching the hijackers off guard and the situation resolved. Baader was flown back from the desert to Stammheim where he was shot and dumped in his cell.

There was never any mention of sand as far as Prosecutor Christ was concerned. He had simply overlooked that vital piece of evidence not ever considering that anyone would look carefully at the exhibits and logs in minute detail.

Three weeks after Prosecutor Christ closed the case a report came from the laboratory in Wiesbaden which was intercepted by MI6 agents, copied and allowed to carry on its postal journey.

The report described the investigation into ‘substances adhering to the shoes of Andreas Baader.’ Professor Holczabek had pointed out traces of sand on Baader’s shoes. He was the only one to do so. He had inquired whether Baader had been allowed to go for a walk. In the cell, the dirt on the floor near Baader’s feet was removed with sticky tape. Three months later on the 26 January 1978, the Wiesbaden laboratory sent for samples from the exercise yard where seventh-floor prisoners were permitted to take fresh air.

The tests proved that Baader had got sand on his shoes: ‘a mixture of fine, light and dark particles that had become stuck together. There were also minute pieces of gravel.’

Where did the sand come from? Why was Baader so happy that he was looking at imminent release?

The answer is Mogadishu!

How guns came to be in the possession of the inmates was another serious issue. The authorities tried to suggest that defence lawyers could have taken them in but that was simply a no-go area. The 7.65 Heckler and Koch pistol by which Baader died can be stripped down into 44 pieces and easily reassembled using a nail file. But the same is not true of the 9mm caliber pistol found next to Raspe.

When the authorities needed an escape clause, they found it although no one truly believed it. Between the 20 October and 6 December, security specialists made an astonishing series of discoveries that seemed to corroborate the official line. In secret hiding places such as behind skirting boards and electronic fittings in and around the cells and rooms used by Baader, Ensslin, Raspe and Karl Croissant (the imprisoned Baader Meinhof defence lawyer) were found a minute transmitter radio, several caches of explosives, razor blades, a stomach pump, a pistol, ammunition and a small loudspeaker that may have been used for sending and receiving Morse code.

It was further revealed that on the seventh floor of Stammheim there was an ‘extra’ fire escape door that could be opened only from the outside as well as a communications network between the prisoner’s cells.

No explanation was given as to how this system had escaped detection until after the high profile and extremely convenient deaths.

The order to the German Government to ‘resolve the Baader Meinhof” problem came from President James Earl Carter, Jr, better known as Jimmy Carter. The Baader Meinhof clan had targeted US interests in Germany and Americans were killed.

The murder of the ring leaders in such a brazen fashion was an example to those that followed the State would not tolerate terrorism and it would be dealt with not always within the law.

The policy was clear: those that hurt US interests will be targeted, hunted and tracked down and killed. Baader Meinhof became precedents for such a policy that has continued.

On the 8 February, 2010 Giovanni Di Stefano better known as the Devil’s Advocate wrote to the Public Prosecutor being aware of the facts surrounding the case.

In December 2010 after the Stuttgart Public Prosecutor reviewed the ‘files’ they were sent back to the Baden-Wurtemberg State archives in Ludwigsburg.

The murder of key members of the Baader Meinhof gang was State sponsored but effective. The Red Army Faction ceased operations in 1993 and ‘officially’ disbanded in 1998.

Irmgard Moller the only survivor was released in 1995 from her life sentence. She has not been heard of since.

Astrid Poll was arrested by Special Branch Officers in 1978 in London whilst working in West Hampstead. Despite having committed no offences she was detained allowing Germany to issue an extradition request. She contested such but eventually returned to Germany. There, Proll’s attempted murder charge was dropped when it was gathered that the State had withheld information that could have cleared her but she was still sentenced to five and a half years imprisonment on account of bank robbery however, she had already spent at least two-thirds of that time in German and English prisons and therefore was released immediately. The British Home Secretary banned her for life from entering Britain.

No one has ever been prosecuted for the multiple murders of the Baader Meinhof gang whilst in custody.

GDS

Red bader group member were exeuted by German commando. Uet, US protects Antifa members posing greater threat that Red Bader. USa is no longer democratic country but Nazi controlled (Antifa) terror groups.

Lola, I’m not sure what warped reality you’re living in, but its not this one. You apparently do not know what ANTIFA represents. It literally means “antifascist”, which means they fight Nazi’s. The US government has shown willingness to more harshly treated self-identified ANITFA, than white supremacists and self a identifying Nazi’s. You’re clearly a sheep or a shill for the conspiratorial Right that actually is trying to instill fascism in the US. Go educate yourself, so you can actually have an original thought.

I think it is you who needs to be educated Anna.

Anna by calling ANTIFA “antifascists” you are buying into their propaganda. They are no different from Nazis, Facists and Communists because they hate democracy and use violence and intimidation to further their political agenda

Doesn’t matter. The pieces of shit are dead and forgotten