Now a new top documentary on Paramount Plus now!

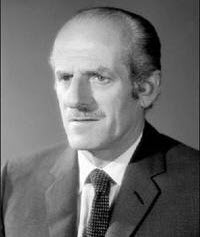

On 18 June 1982, the body of a top Italian Banker was found hanging from Blackfriars Bridge in London, he was better known as ‘Gods’ Banker’ for his links with the Vatican. He was 62-years-old and called Roberto Calvi, the Chairman of Banco Ambrosiano, in Milan, and a central figure in a complex web of international fraud and intrigue.

Robert Calvi

Robert Calvi

Calvi had been missing since Friday, 11 June 1982. He’d arrived in London on 15 June 1982, days before his body was discovered by a passer-by hanging from scaffolding on a riverside walk under the bridge.

Calvi had been missing from office since Friday, 11 June 1982, taking a detour, he arrived in London, unknowingly, on 15 June 1982; days before his body was discovered hanging from scaffolding on a riverside walk under the bridge, by a passer-by.

Immediately, and without any investigation, the City of London Police treated the discovery as suicide.

Calvi was the Chairman of Banco Ambrosiano, Italy’s largest privately-owned banking group and, from 1975, had built up a vast financial empire. In 1978, a report by the Bank of Italy on Banco Ambrosiano concluded that billions of the then, Italian Lira. had been illegally exported and transferred to correspondent banks abroad. This aspect was then treated officially as pure fraud but was vital as to why and who murdered Calvi.

Calvi was the Chairman of Banco Ambrosiano, Italy’s largest private bank, and, from 1975 had built up a vast financial empire. In 1978, a report by the Bank of Italy on Banco Ambrosiano concluded that billions of the then Italian Lira had been illegally exported and transferred to correspondent Banks abroad. This aspect was then treated officially as pure fraud but was vital as to why and who murdered Calvi.

In 1981 in Italy, Calvi was arrested, found guilty, and sentenced to four years imprisonment, but released pending an appeal. During his short spell in jail, he even supposedly attempted suicide. Calvi was due to appear in an Italian Court, within days of his death, to appeal against this conviction.

In July 1982, he was to be tried for alleged fraud involving property deals with Sicilian banker Michele Sindona, who himself was then serving 25 years in America over the collapse of the Franklin National Bank in New York in 1974. Sindona was also subsequently murdered.

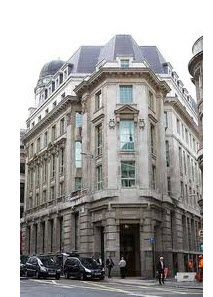

Archbishop Paul Marcinkus

Calvi had fled to Venice, nine days previously, after shaving his moustache to avoid being recognised, and from there it seems he hired a private plane to take him to London. The day before he was found dead, his secretary committed suicide in Milan by purportedly jumping off the fourth floor of the Bank’s headquarters. Teresa Corrocher, 55, left an angry suicide note condemning her boss for the damage she said he had done to Ambrosiano and its employees.

To all intent and purposes, it was an open and shut case, and to most, it was ‘good riddance’ Mr Calvi.

It was subsequently announced that Calvi had seven large bricks in his pockets (supposedly) and approximately $14,000 in cash in three different currencies, Italian Lira, Swiss Francs, and British Sterling. On his wrist an expensive Philippe Patek Watch. In his pocket a passport in the name of ‘Gian Roberto Calvino’. Robbery was clearly not the motive.

Professor Frederick Keith Simpson, England’s most experienced pathologist, and a man I had pleasure subsequently at discussing the findings concluded the autopsy. He found no river water in his lungs. The cause of death was asphyxia by hanging. Since his neck had not suffered the kind of injury that would have occurred in a free-fall, he determined that Calvi could not have dropped more than two feet before his fall was broken by the water. There was no medical evidence whatsoever of foul play, such as marks on the arms, to indicate he had been restrained, puncture marks on the skin to indicate he had been injected with a drug, and no traces of suspicious chemicals in his stomach of drugs, other than the residue of a sleeping pill he had taken the previous night.

Other non-medical clues, however, made the possibility of suicide more problematic. The Patek Philippe Watch established the time of death, though finely crafted, it was not waterproof. Its hands had stopped at 1:52 am. While the Watch could have stopped for reasons other than water damage, the watermarks on the face of it, when taken, together with the dropping level of the tide that night at Blackfriars Bridge, established the latest time at which his body could have been suspended from the scaffolding. After 2:30 am, the level of water in the Thames at Blackfriars Bridge would not have been high enough to reach Calvis’ wrist, as was calculated from the length of the rope he was hanging by when he was found, so, he must have been hanging before then. However, he could not have hung himself before 1:00 am, because the river level then would have been above his mouth, and there was no river water in his body. So, if he committed suicide, it could only have been between 1:00 am and 2:30 am.

Despite what was evidently clearly not suicide but murder. A Coroner’s inquest presided by Dr David Paul and a jury returned a verdict of suicide on 23 July 1982, less than a month after the discovery of his body, and the whole proceedings lasting just one day.

The inquest started at 10:00 am on Friday, 23 July. The evidence finished at 7.20 pm. That lapse of time is 9 hours 20 minutes, of which 1.55 hours, roughly speaking, was taken with breaks for lunch. There was a half-hour break between 7:20 and 7:50 pm. That was to enable the Coroner to retire to his room and to collect his thoughts, in order, to prepare himself for his summing up to the jury. The summing up itself was brief; it took from 7:50 until 8:20 pm. The jury then retired, and it is worth noting that the time at which they retired was no less than 10 hours and 20 minutes after the inquest had started.

At 9 pm it appeared that they were unable to agree on a unanimous verdict. A majority direction was given and, at 10 pm, the majority verdict to which reference had already been made, was reached.

It is perfectly true that the advocates, Sir David Napley and Mr Blofeld, were given the opportunity by the Coroner to call a halt if they wished, but they did not do so. There is no doubt that the jury could, technically at least, have objected and said, “We want to go home”. They did not. So, the result was that they were delivering their majority verdict some 12 hours after the inquest had started.

The Coroner gave the following direction to the jury:

“Well now, members of the jury, I’ve got to try and make sense of all this, in the course of summing up. I trust you are comfortable, I could say my summing up is going to take all of two hours, I assure you it will take very considerably less and if you do require an adjournment you may have one until, good heavens, a quarter to eight at night. This is breaking almost every rule in the law courts. We will reassemble at a quarter to eight, I will then sum up to you and send you out and with any luck, we should be away from here soon after.”

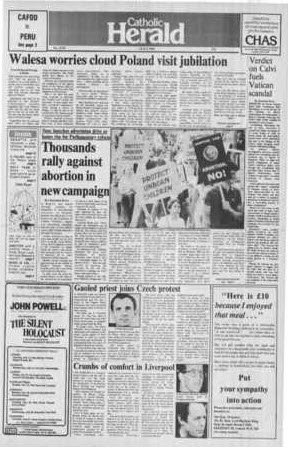

It was no wonder that Lord Lane, the then Lord Chief Justice, sitting with Mr Justice Taylor, later to be Lord Chief Justice, and Mr Justice McCowen had no hesitation in quashing that verdict. But that was on 29 March 1983, and almost a year after the end of the undeclared war between Britain and Argentina.

In July 1983, a second Coroner’s verdict overturned the previous verdict of suicide and substituted such with an ‘open verdict’, a degree less shameful.

Quite ironically, on 19 June 1975, a Coroner’s inquest jury returned a verdict of murder on Lord Lucan for the murder of his nanny, Sandra Rivett, on 7 November 1974. That jury also consisted of six men and three women, as in the case of Calvi. The exception was that the Westminster Coroner, Dr Gavin Thurston, went in person to the Central Criminal Court immediately after the verdict and issued a warrant for the arrest of Lord Lucan.

Like Lord Lucan, however, the murderer of Roberto Calvi would never stand trial.

So, who killed Roberto Calvi?

Italian prosecutors would like us all to believe that Pippo Calo, a mafia gangster, already serving a long prison sentence since 30 March 1985; Flavio Carboni and Ernesto Diotallevi – supposedly the leader of the ‘Banda Della Magliana’, described as a go-between and Carbonis’ Austrian girlfriend, Manuela Kleinszig, are the perpetrators!

Calvi Francesco di Carlo

The basis of the allegations rests upon statements made by the so-called collaborator with Italian justice and convicted murderer, Francesco Di Carlo. It was Di Carlo that was convicted in the United Kingdom, served sentences of imprisonment in Brixton Prison and Parkhurst, and transferred under the Prisoner Repatriation Scheme to Italy, where he began giving information to the Italian Investigative Magistrates. As a collaborator with justice, Di Carlo has earned considerable benefits. The most important being his premature freedom.

Other names that have come in the frame are Licio Gelli and a supposed smuggler from Trieste, mysteriously murdered, Luciano Vittor.

Each year, more and more names are introduced complicating the matter and detracting from the real truth behind the murder of Roberto Calvi, which had nothing whatsoever to do with the Mafia, The Vatican, or organised crime.

To complicate matters further, Carboni is alleged to have links with the previous Minister of Interior in Italy called Giuseppe Pisanu, and it is said that our ex-Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi, was actually introduced to Pisanu by Mr Carboni in connection with certain potential investments in the Costa Smeralda. Frankly, all stories to detract from finding the real murderers of Roberto Calvi.

What I do know is that when I was at MGM between 1989 and 1992, within the telephone directories that were handed to us were included the names ‘Flavio Carboni’, ‘Pisanu’, ‘Bernasconi’, ‘Licio Gelli’ and ‘John Gotti’.

However, all of the above is only introduced into the theatre of murder to defray from identifying the real murderer of Calvi.

In the United Kingdom between 1979 and 1982, the head of MI6, better known within the trade as Military or External Intelligence, was Arthur Franks (Sir, and nick-named ‘Dickie’) and from 1982 to 1985 Colin Figures. The head of MI5, or Internal Intelligence, between 1981 and 1985 was Sir John Jones.

Vitaly Fedorchuk

In Russia, the head of the KGB, in 1982, was Vitaly Fedorchuk and strangely in 1982 until 1988, Viktor Chebrikov. In the USA from 1981 to 1987 the CIA Director was William J Casey, under President Reagan.

In 1982, in Argentina, General Galtieri was not only the military leader but also as head of State assumed the role of head of Argentina’s Military Intelligence Services.

General Galtieri

But what has all the above to do with Roberto Calvi?

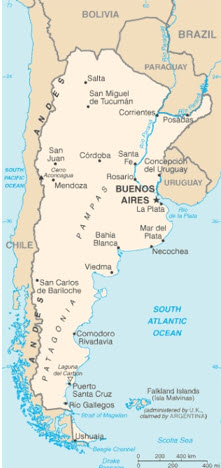

On 2 April 1982, Argentina launched ‘Operation Rosario,’ which was aimed solely at the retention of the Falkland Islands from the United Kingdom.

The British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, ordered the British Navy to prepare mobilisation and the beginning of what was to be known as ‘Operation Corporate.’ Below is the timetable of events:

0600: Falkland Islands Governor, Rex Hunt, mobilises 100 men – Royal Marines plus some 20 local volunteers, after warning residents by radio of an impending invasion. After receiving intelligence that the invasion had begun, Governor Hunt says: “It looks as though the silly buggers mean it.” Rear Admiral Jorge Allara, Commander of the Argentine flagship ‘Santisima Trinidad’, appeals for a peaceful surrender. The request is rejected. At the same time, small units of soldiers begin landing near the capital, Stanley.

0945: Mrs Thatcher holds the first of two emergency cabinet meetings and asks her Government to back a naval task force.

1015: Islanders hear gunfire and explosions. Some 40 soldiers seize empty barracks at Moody Brook and head towards Stanley. Argentinian units attack Stanleys’ Government House, defended by less than 50 men. The emergency cabinet meeting in London agrees to reconvene in the evening.

1100: Argentine forces come ashore six miles from Stanley and head for the airstrip. A fierce firefight begins at Government House.

1300: Argentinian forces clear the airstrip and fly in the 25th Regiment. Argentina’s Captain, Pedro Giachino, becomes the first soldier to die, killed in the assault on Government House. The rest of the town is under Argentine control.

1325: Recognising the growing strength of the Argentinian forces, Governor Hunt orders a ceasefire and surrenders. No Falkland Islanders or Royal Marines have been killed, though one serviceman is badly wounded. The Argentine flag is raised over Government House. In Argentina, the head of the military junta, General Galtieri, hails the ‘recovery’ of the Malvinas, saying it had been left no other option than military action.

1400: The UK orders Argentina’s diplomats out of the country. The Bank of England freezes Argentinian assets in the UK. Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington confirms in Parliament that ‘Port Stanley is now occupied by Argentine military forces.

1800: The majority of the British public learn of the invasion on the early evening news. Argentine forces make preparations to fly the Royal Marines and Governor Hunt off the islands. In London, the cabinet backs the proposed naval task force during the days’ second cabinet meeting. MPs are recalled for a special Saturday sitting of the House of Commons. In New York, the British representative to the United Nations, Sir Anthony Parsons, puts a draft resolution to the Security Council condemning the hostilities and demanding an immediate withdrawal of forces. The resolution is later approved 10 votes to one (with four abstentions) The United States sides with London.

2200: The first nine ships of the British naval task force finalise preparations for battle. They will leave within hours for a three-week voyage to the south Atlantic.

All very interesting but what has it to do with Roberto Calvi?

The Falklands/Malvinas conflict provided several combat situations, several of which were deemed ‘firsts.’ Some of these included:

The first use of modern air-launched cruise missiles against Warships of a major Navy. The first use of helicopters in an anti-shipping role employing guided missiles. The first time since World War II a major Navy has fought an opponent that employed air, surface and sub-surface forces against it. The first time since World War II that sustained air attacks was made against naval forces. The first combat employment of shipboard surface-to-air guided missiles to defend surface naval forces against sustained air attacks. The first use of nuclear attack submarines in combat. The first use of high-performance V/STOL aircraft in combat. The first use of passive night vision goggles by helicopter crews for the movement of troops in combat.

But what has all this to do with Roberto Calvi?

The Falklands/Malvinas conflict was fought between two very different countries possession remarkably different skills and capabilities. At the strategic level Argentina, a continental power with maritime leanings challenged a maritime power that had almost persuaded itself to adopt a continental strategy.

The most capable, most modern aircraft in the Argentine Navy inventory was the French-built Dassault Breguet Super Etendard tactical jet. Primarily a subsonic attack aircraft (maximum speed 640 knots), the Etendard carries two 30mm cannons and can be loaded with bombs, rockets or additional fuel tanks. The aircraft can also be fitted with the Matra Magic air-to-air missile for a limited anti-air role. The Etendard’s primary mission in the Argentine Navy, however, involves the launching of Exocet AM-39 missile.

In September 1980, fifty pilots and technical personnel of the 2nd Air Naval Fighter and Strike Squadron of Argentine Naval Aviation Command (CANA) arrived at Rochefort Naval Base in France. Among the group of pilots were the unit’s Commander, Frigate Captain Jorge Colombo, and sub-Commander, Corvette Captain Augusto Bedacarratz. The rest of the pilots were: Corvette Captains Roberto Agotegaray, Roberto Curilovic and Alejandro Francisco, and Warship Lieutenants Luis Collavino, Julio Barraza, Juan Rodriguez Mariani, Armando Mayora and Carlos Machetanz. All the pilots had hundreds of hours of flying A-4Q Skyhawks, the main type of combat plane used by CANA by that time.

After three months of French language teaching, they were sent to Landivisiau Air Naval Base, where they flew training sorties in Morane Saulnier planes during 30 days and then began to know their future combat tool, the AMD-BA (Avions Marcel Dassault – Breguet Aviation) Super Etendard. Later, the Argentine pilots started to learn the basic flight lessons in the Super Etendard (a maximum of 50 hours of flight by each pilot) and basic notions about the weapon systems, especially the anti-ship missile, AM.39 Exocet. The technical specifications of these are:

AMD-BA Super Etendard

Engine: turbojet SNECMA Atar 8K-50 with a throttle of 5,000 kg.

Top speed at sea level: 1200 km/h.

Ceiling: 13,700 m.

Range flying at sea level: 720 km.

Weapons: two 30mm cannons, and 2,270 kg of weapons load (including bombs, air-to-air, R.550 Magic missiles and anti-ship AM-39 Exocet missiles).

AM.39 Exocet

Type: airborne ‘fire and forget’ anti-ship missile.

Length: 5.2 m.

Diameter: 35 cm.

Wingspan: 1 m.

Weight: 655 kg.

Range: 70 km.

Cruise speed: 1100 km/h (Mach 0.9).

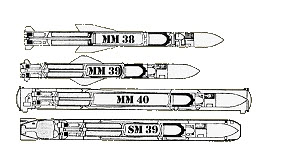

Left: The Exocet family. The SM.39 is the submarine-launched version, while both the MM.38 and MM.40 are the ship-to-ship versions. The last member of the family is the AM.39; the air-to-ship version. This was the type of missile used by the Argentine 2nd Air Naval Squadron.

To attack a ship with the AM.39 version requires a work of two stages: first, the missile is guided by the plane’s fire control system, which gives to the missile the target’s coordinates and these coordinates are obtained by the plane’s radar. When the missile is launched, it dives to an altitude of 30 meters, which is later fixed at only 2.5 meters by the missile’s radio altimeter. In the few final seconds of flight, the missile activates its radar and searches for the target. If it finds any, the missile locks onto it and guides itself to the impact point.

The Argentine pilots and technicians returned to Comandante Espora Air Naval Base, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, in July 1981, and began the preparation for the arrival of the first five Super Etendards, which finally happened in November 1981. The Argentine Navy had ordered a total number of 14 aircraft, and the same number of Exocets. The Argentine pilots tested the navigation system of the five planes as much as they could and started to do the same with the weapons system.

The Argentines ordered fourteen of the Super Etendard aircraft from France, in 1979. Plans called for a ten-plane squadron with four aircraft in reserve. To ensure the highest level of training for the pilots, they added a Super Etendard flight simulator. This simulator had not arrived prior to the South Atlantic conflict.

It is important to remember that deposits had been paid for the order of aircraft, but full payment was expected only when the delivery was ‘imminent’, according to the contract. Delivery was delayed in 1981, but was expected within the month of April 1982 and no later than May 1982, according to the annex in the contract. This was to be a vital aspect which caught Calvi in the web of death.

By the start of the South Atlantic conflict in early April, the pilots had accumulated an average of only 90 flying hours each. None had received any training in the delivery of the Exocet missile. French technicians were to have made the missile operational in April of 1982 but had been recalled to France once the war had erupted. Or so it was thought!

Thus, the Navy’s Super Etendard squadron actually began the War with just five aircraft, five Exocet missiles, and no training in the employment of the missile. To top it off, the necessary modifications to the carrier Veinticinco De Mayo had not been completed in time for the aircraft to be deployed aboard ship. The pilots improvised their own training and tactics, however, and did get limited assets combat-ready. Flying from shore bases, they conducted a total of ten sorties, launched all five missiles, and scored two or three hits, destroying two ships and shocking the world with the lethality of the advanced weapon system. It is interesting to speculate as to the impact the aircraft might have made on the British fleet had more Exocet missiles been available at the time of the hostilities.

It is indeed and this is what was the primary cause for the murder of Roberto Calvi

Probably no other weapon of the South Atlantic conflict captured more attention than the Exocet missile. To be sure, it did not mark the first sinking of a ship by a sea-skimming missile. The Israeli Destroyer Eilat had been sunk by Soviet missiles fired by Egyptians in the 1967 war. There were other reports of the use of anti-shipping missiles during the Iran-Iraq War which had begun in 1980.

Nonetheless, those instances were generally ignored, probably because they were fights among vessels belonging to third rate navies. The sinking of HMS ‘Sheffield’, a ship belonging to a major seagoing nation, took the whole world by surprise. The fact that a $50 million vessel could be sunk by a single hit with a relatively inexpensive ($250,000) missile was shocking, to say the least.

The French-designed Exocet AM-39 missile used by the Argentines is the aircraft launched a version of the widely used Exocet anti-shipping missile. The AM-39 has a two-stage solid-fuel rocket motor, with a burn time of approximately 150 seconds. This gives the missile a high cruising speed of Mach .93 at a height of only 6-10 feet, and a range of approximately 30 miles. This missile is 15 feet long, has a warhead of 360 lb. and a total weight of 1430 lb. The AM-39 version receives target range and direction data from an I-Band radar in the Super Etendard aircraft prior to launch. The guidance system consists of inertial guidance followed by active radar homing when the missile approaches five miles from the target.

A total of five AM-39 missiles, the entire Argentine inventory at the start of the conflict, were fired. One missile struck HMS ‘Sheffield’ and one, possibly two, struck the container ship ‘Atlantic Conveyor’.

Curiously, it is believed that neither, or none, of the warheads, exploded. Rather, the ships were destroyed by fires which were started by the still-burning rocket motors. Authorities are reluctant to speculate why the warheads failed to detonate because the two vessels sank, no missile parts could be recovered for analysis.

None of the AM-38 missiles (the ship-launched version of the Exocet) installed aboard Argentine Navy ships were fired from their vessels. Several AM-38s, however, were removed from the ships and fastened to truck trailers for use as land-based mobile anti-ship batteries. At least two missiles were fired from these shore-based launchers. One struck HMS ‘Glamorgan’ and exploded, destroying the ship’s helicopter and hanger, but did not sink the ship. That was the Exocet missile!

So, who killed Roberto Calvi and why?

Following independence from Spain in 1816, Argentina experienced periods of internal political conflict between Conservatives and Liberals and between civilian and military factions. After WWII, a long period of Peronist authoritarian rule and interference in subsequent governments was followed by a military junta that took power in 1976. ‘Democracy’ returned in 1983, and numerous elections since then have underscored Argentina’s progress in democratic consolidation. That is what is said in short about Argentina.

There is a population of approximately 40 million with some 60% being the ages of 15-64, and approximately half divided equally between male and female. The heritage of the country is 97% Italian-Spanish! 90% of the population are Catholics. The official language is Spanish, but the most spoken being Italian and English. Its literacy rate is 97%, with a highly educated population. Between 1975 and 1982, it was a haven for the likes of Calvi and his Banco Ambrosiano. So, were other countries within South America. The advantage of Argentina was that it was predominantly Italian and the language of Calvi. It was a country that was, according to CIA reports on Calvi, ‘easy to do business with’.

What off, however, the four persons standing trial for the murder of Roberto Calvi?

Flavio Carboni was certainly no friend of Calvi. In 1981, when Calvi was first arrested and subsequently released, it is true to say Calvi felt ‘lost’ and abandoned by all. An Italian Secret Service agent was his first port of call to allow him a certain mediation with the Vatican. His name was Francesco Pazienza. When that failed, Calvi indeed turned to Carbone. At a meeting with Carbone in early 1982, intercepted by GCHQ and subsequently transcribed but not made available to the Italian Courts or prosecutors, Calvi clearly promised Carbone 120 Billion Lira to be divided equally, and used as bribes for (a) the Church (b) the politicians (c) the media and (d) Freemasons, provided that Carbone could get Calvi ‘out of the shit’.

Flavio Carbone did not murder Roberto Calvi neither did he have anything to do with his murder

It is quite incorrect to say that Licio Gelli has been the beneficiary of much of the misplaced funds from Banco Ambrosiano and, upon the death of Calvi, there has been a witch hunt against Gelli. I have met Mr Gelli and was in the South of France when he was arrested. Other than taking advantage of his name and his supposed reputation, Licio Gelli did not murder Roberto Calvi.

Much has been said about Francesco De Carlo and that he was the Mafiosi killer acting with a worldwide mandate. The British authorities took little to no time in arresting him from his home in Surrey and jailing him for drug offences. Under the Repatriation of Prisoners Scheme, De Carlo was indeed returned to Italy where he found solace in confessing his supposed crimes to the Italian Magistrates, and some tall stories, earning him many favours in prison comfort. It is said, that he has at times confessed to the murder of Roberto Calvi and other ‘pentito’ have also confirmed what they had heard or thought to be that De Carlo had strangled Calvi. Francesco De Carlo did not murder Roberto Calvi.

That Roberto Calvi did not suicide himself is without a doubt. Suicide during those hours, if possible, at all, would require extraordinary activities from a 62-year-old man, who was overweight and suffered from vertigo. Despite the darkness, he would have had to find the scaffolding from the walkway along the river, which, since it was nearly submerged, could be seen only by leaning over the parapet wall at a strategic point. He would also have to have found in the dark the bricks, which were identified as coming from a construction site about a block away, and the rope to hang himself. Next, he would have to have hoisted himself over the parapet on the bridge and climbed twelve feet down a nearly vertical iron ladder to the level of the temporary scaffolding. He then would have to step across the two and one-half feet gap onto the scaffolding’s rusty poles, which were arranged like monkey bars in a children’s playground, and edge his way about eight feet along them to tie the rope to the eyelet. After that, he would have had to shimmy down to the next level of the scaffolding (otherwise the drop from the higher level would have resulted in obvious neck damage). Finally, having put the bricks in his pockets and pants fly, and his head in the noose, he would have had to ease himself into the swirling water three feet below by clutching onto the poles (again, avoiding a free-fall).

While such an acrobatic movement is, in theory, possible, it would presumably have left some traces such as rust under fingernails, splinters, or abrasions on his hands, or tears in his suit. ‘The long and short of it is we do not know how Calvis’ body got onto the end of that rope,’ Deputy Superintendent John White explained to the media. “We don’t even know how he got from his hotel, four- and one-half miles away, to Blackfriars bridge.”

It was clear to the City of London Police in 1982 that suicide was not an option. There was, for example, no neck damage to the corpse of Roberto Calvi excluding thus death by hanging. There were no traces on the soles of his shoes, which should have been the case if Calvi had climbed up scaffolding and then hung himself. There were no traces of paint on the soles of his shoes or any other chemical, totally thus excluding the possibility of suicide. Yet, when the inquest took place shortly after a victorious United Kingdom over a bruised Argentina, it was necessary for the whole chain of conspiracy to murder to remain intact. That chain would include the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Dickie Franks, Sir John Jones, and some of the most senior operatives of the Security Services that were working on the Calvi solution since May 1982, when the British discovered that Banco Ambrosiano and its subsidiaries, including ‘La Centrale’ was the operative Bank for the Argentinian Government, and specifically the effecting of payments for military hardware left in suspense, including the dreaded Exocet missile.

So, let us examine now the suspect in this murder, for murder is what it was and remains.

When Calvi had been jailed in Lodi Prison for 42 days in 1981, on a technical charge of evading currency exporting rules, he had summoned these Magistrates to his cell in the dead of night and volunteered information about what was one of Italy’s most taboo – and dangerous – subjects: the funding of political parties. He limited his disclosures to an ambiguous $21 million loan to the Socialist Party but added, tantalisingly, that if he had the ‘research opportunity’ he could furnish more ‘precise’ documentation. The extent of the potential damage was explained in 1989, by the former finance director of ENI, Florio Fiorini, who was himself arrested in 1992. He was, it must be remembered, a fellow director and co-owner of MGM, and we knew each other very well. He said he had met with Calvi the night he disappeared in Milan with his black briefcase to discuss an eleventh-hour rescue with ENI funds of Banco Ambrosiano. He had been given this urgent assignment by his superiors at ENI. They would deny it later but, according to Fiorini, they were acutely concerned about the growing pressure on Calvi.

Florio Fiorini

Florio Fiorini

Most of the money that Calvi had been using in his offshore activities came from ENI (it was ENI deposits that had been siphoned through the Bellatrix ghost into the P-2 accounts). Even of greater concern, according to Fiorini Calvi had intimate knowledge of the subterranean channels through which ENI, and other state-owned enterprises, put money into the ‘black accounts’ of politicians of the major parties. The previously discussed protection account was merely one of many such routes. Fiorini, surmised from his conversations with Calvi that he might have records bearing on other aspects of the bank’s liaison with ENI. How incendiary this information could be was demonstrated in February 1993, when, within days after Calvis’ bribe was confirmed, criminal charges were lodged against the Justice Minister, Claudio Martelli, and ex-Prime Minister, Bettino Craxi. That is a short précis of the political aspirants to the murder of Calvi. But the Socialist Party did not murder Calvi.

The P2 Masonic Lodge? Let us see:

Juerg Heer, who had been Executive Director of the credit section of Zürich’s Rothschild Bank, when it acted as an intermediary in Calvis’ abortive takeover of the Rizzoli Group, claimed to have paid the fee for the murder of Calvi. The Rizzoli deal was Calvis’ last deal, which he himself described as his ‘undoing’ just days before vanishing.

Although Heers’ name does appear in the bank’s correspondence about Rizzoli, his relevance to the Calvi affair emerged only after he was abruptly fired by the Rothschild Bank, in July 1992. Accused, by the bank, of exceeding his authority in arranging bad loans, he was imprisoned for two months and, adding insult to injury then sued by his former employer to recover its losses. Heer, retaliated by airing the Rothschild Banks’ dirty laundry in public, asserting he ‘was part of a criminal system’. As the vendetta escalated, he dredged up sensitive details about Calvis’ Rizzoli deal.

As the intermediary, the Rothschild Bank had acted to shield the true principals, including one of the most intriguing conspirators in Europe, Licio Gelli – a self-styled poet whose machinations were subsequently documented in a 64-volume investigation by a Commission of the Italian Parliament. Gellis’ power proceeded from the secret Masonic Lodge in Rome, Propaganda Due, or P-2, as it was called, of which he was Grand Master. Among the 900 elite members he had enrolled were 43 members of Parliament, 48 generals, the heads of Italy’s secret intelligence service, the top magistrates in the judiciary system, the civil servants running various state-owned enterprises (including ENI), key bank regulators and leading businessmen – a veritable. The Parliamentary Commission described it as a ‘state within a state’. Unlike other Freemason lodges, it did not hold meetings or conduct ordinary Masonic business. Whatever its supposed purpose, by the time Calvi had enrolled in it in 1980, it had become a clearinghouse through which businessmen could by political protection from government officials, with Gelli acting as a go-between, deal maker and record keeper.

In this Rizzoli deal, Gelli, together with other P-2 associates, including the managing Director of Rizzoli, had parked a controlling block of its shares at the Rothschild Bank. Calvi then had his banks lend $142 million to a ‘ghost’ corporate shell in Panama, called Bellatrix, which deposited it at the Rothschild Bank to buy the shares. As a crucial part of the arrangement, Bellatrix paid an artificially high price for the Rizzoli shares, about ten times their market value, to generate a windfall profit for the P-2 organisers of this deal. This huge inflow of money from the Panamanian ‘ghost’ occasioned frightening concern at the Rothschild Bank. According to Heer, a Rothschild Director told him, ‘We have to find a solution or I will end up in Lake Zürich’.

The solution they found was to temporarily put the Bellatrix money into two accounts at the bank – called Zirka and Reciota – under a discrete fiduciary. However, within days, it was released into other numbered accounts controlled by Gelli and his P-2 associates. So, the $142 million borrowed by Calvi disappeared into P-2 havens, destined for unknown uses.

The problem, as it turned out, was that Calvi did not receive the permission he needed from the Italian authorities, for Banco Ambrosiano’s Luxembourg subsidiary to take control of Rizzoli. On the contrary, Italian law was changed so as to make the transfer impossible, which meant, as far as Calvi was concerned, the Rizzoli deal had not been technically consummated. So, in theory, the $142 million that the P-2 men had, still belonged to his Bank. According to his personal assistant, Calvi regarded this money as a ‘reserve fund’, and had been pressing the P-2 men to return control of this money in 1982, without success.

By that June, with his ‘ghosts’ having no way to repay their debt, this money was the difference between ruin and temporary salvation, and Calvi headed for Zürich – a destination he never reached.

Shortly after Calvis’ body was found, Heer carried out a ‘secret operation’ at the request of one of Gelli’s associates. Heer, estimated that about $5 million drawn from Gelli’s account in Geneva, which he identified as part of the missing Bellatrix funds, was packed in a suitcase and delivered to him at the Rothschild Bank. He also received one half of a $100 bill. Following his instructions, he gave the suitcase to two strangers who later arrived at the Bank with the matching half of the bill, and who left with the money in an armoured limousine. Subsequently, he learned from a ‘family member’ of Gellis’ that this money had been used to pay for Calvis’ murder.

Banking records produced, in the various investigations of the bankruptcy, confirmed that most of the Bellatrix money, diverted through the Rothschild Bank, went to Gelli and his P-2 associates. Gelli, in fact, had been arrested in Geneva that September making a withdrawal of $55 million from his account and, after first escaping and then being re-arrested, he was sentenced to 18½ years in prison for contributing to the fraudulent bankruptcy of Banco Ambrosiano. Licio Gelli is not in prison and did not murder Roberto Calvi.

The Mafia?

In July 1991, Francesco Mannoia, a Mafia ‘pentito’, whose entire family had been killed since he began cooperating with the authorities, told the Rome public prosecutor that he had learned from a colleague, in Sicily, that Calvi had been strangled by Francesco De Carlo on orders from Mafia boss in Rome, Pippo Calo. De Carlo, who had been residing in London in 1982 and whom I have met, was serving out a 25-year sentence, subsequently reduced to 22 years, in a British prison on a drug conviction. Although he denied the allegation and subsequently changed his mind on several occasions to various investigators, Kroll investigators found a credit slip that had been impounded in the drug investigation of him that showed that $100,000 had been deposited in his account at Barclay’s Bank on 16 June 1982 – one day before Calvi disappeared. But De Carlo did not murder Roberto Calvi.

The Vatican?

In May 1988, Judge Mario Almerighi, in the process of preparing the case against a gang of importers of hashish and heroin, found among the material that had been seized in a police raid, correspondence addressed to one of the highest officials in the Vatican Curia – the Secretary of State of the Vatican, Cardinal Agostino Casaroli.

The two letters asked the Vatican for 1.5 billion Lire (about $1 million) to reimburse the drug smuggler for funds he had advanced to Flavio Carboni to acquire documents written by Calvi. When he checked with postal authorities, he found, to his astonishment, that both letters had been sent by registered mail and signed for by an official in the Cardinal’s office.

As he probed deeper into this affair and interrogated those involved, he discovered that the documents in question had come from the black briefcase Calvi had taken with him to London. Carboni had delivered documents to a Vatican Bishop who had given him cheques drawn on his account at the Institute for Religious Works, IOR, the Vatican’s central – and only – Bank. Tracing the Bishop’s cheques through the IOR and other banks, he determined that Carboni had received at least 3 billion Lire (about $2 million); ‘All of it was Vatican money,’ he explained. A memorandum he found further suggested that the Vatican had been willing to pay $40 million for other Calvi documents, which Carboni had not delivered.

Calvis’ black case had not been found in Calvis’ locked room in the Chelsea Cloisters, so, presumably, Calvi took it with him the night he died. No-one admitted seeing it afterwards until it dramatically resurfaced on Italian television on 1 April 1986, along with Carboni and Vittor, who vouched for its authenticity.

Even though Vatican officials insisted that the Bishop had acted without their approval in paying for these documents with IOR funds, Judge Almerighi found in the documents he had retrieved enormous potential for extortion. One letter that Carboni admitted that he had delivered to the Bishop had been written by Calvi to John Paul II six days before Calvi fled Italy. Calvi called ‘His High Holiness’ his ‘last hope’, and asked for his urgent help. He explained: ‘It was I who took on the heavy burden of remedying the errors and mistakes made by the present and former representatives of the IOR’ and ‘providing financial aid to many countries and politico-religious associations on the instructions of authoritative representatives of the Vatican’.

In the context of the on-going litigation over the financial responsibility for Banco Ambrosiano’s $1.2 billion, the putative activities described in this letter had serious implications for the Vatican Bank, and its head, American-born Archbishop Paul Casimir Marcinkus, who had also been a director of Banco Ambrosiano Overseas in the Bahamas. In these twin positions, Marcinkus greatly expanded the IOR’s banking business with Banco Ambrosiano.

Since the Vatican is a sovereign state, and the IOR exempt from Italian banking supervision, Calvi took advantage of its privileged status to transfer money from Italy to his Banks’ subsidiaries abroad. The Vatican, however, played no role in the murder of Roberto Calvi.

I have taken time to recount the above from events and knowledge, some first hand, and some relayed to me. People I have met included the following: Francesco De Carlo, Livio Civiletti, Maurizio Sandrelli, Flavio Carbone, Florio Fiorini, Giancarlo Parretti, Margaret Thatcher, Sir Arthur Franks, Sir John Jones, Sir Martin Furnival-Jones, Sir Michael Hanley, Sir Howard Smith, Sir Anthony Duff, Sir Patrick Walker, Stella Rimington, Sir John Rennie, Sir Maurice Oldfield, Sir Christopher Curwen, Sir Colin McColl, David Spelling, George Bush (when he was CIA Director), Turner Stanfield, William Webster, Kerr, Woolsey… and the list goes on and on.

It has taken some time to recount the background to who did not kill Roberto Calvi, but it will only take a few lines to point the finger at who did kill him.

It is not important who the actual person that committed the murder was. As a matter of law, it might be. Carlo Calvi, the son of Roberto and his family will want to know presumably the actual person who committed the murder. It is not important. It is not important at all. What is important is who ordered the murder. It is not even important why, although it is clear.

It is correct to say that the Vatican, the Italian Government, the Mafia, the Freemasons all had ‘bit’ parts in the saga. But, they were not party to the act of murder or the conspiracy to murder. Those that ordered the murder of Roberto Calvi found themselves in a unique position of an almost Agatha Christie ‘whodunit’.

Without him even knowing, the problem that would lead to the untimely death of 62-year-old Roberto Calvi in 1982, started in 1964 when the position of the Falkland Islands was debated by the UN Committee on Decolonisation. Argentina based its claim to the Falklands on papal bulls of 1493, modified by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), by which Spain and Portugal had divided the New World between themselves; on succession from Spain; on the islands’ proximity to South America; and on the need to end a colonial situation, Argentine rule and control of the lives of the Falklanders against their will would, in fact, create one.

In 1965 the UN General Assembly approved a resolution inviting Britain and Argentina to hold discussions to find a peaceful solution to the dispute. The protracted discussions were still proceeding in February 1982 shortly before the Falkland was started.

On 19 March 1982, a group of Argentine scrap metal merchants working in the South Georgia Island are escorted by some military personnel. Britain calls on Argentina to remove the military personnel, without response.

On 26 March 1982, the Argentine military junta decides to invade the islands. Argentina is in deep economic trouble; throughout 1981, inflation sky-rockets to over 600%, GDP is down 11.4%, manufacturing output is down 22.9%, and real wages by 19.2%.

On 2 April 1982, the Argentine Navy with thousands of troops land on the Falklands. A small detachment of Royal Marines on the Island put up brave but futile resistance before Governor Rex Hunt orders them to lay down their arms. The Marines are flown to Montevideo along with the British Governor.

On 3 April 1982, the UN Security Council passes resolution 502, calling for the withdrawal of Argentine troops from the islands and the immediate cessation of hostilities. First Royal Air Force transport aircraft deploy to Ascension Island.

On 10 April 1982, EEC approves trade sanctions against Argentina. US Secretary of State flies to Buenos Aires for talks with the junta. It was on this day that Roberto Calvi was mobilized into action and he saw salvation for himself and his bank. Not from the Mafia, or the P-2, or even the Vatican.

Why and from whom? Because, with trade sanctions imposed by the then European Economic Community, no military hardware could be supplied to Argentina by the makers of Exocet, the French. It was time for ‘Gods’ Banker’ to shine and nurture the relations he already had extensively in South America and Argentina.

At the same time, the French were trying to find a way to ‘promise’ delivery of the military hardware already ordered and part paid for, take money from the Argentine Government and keep the hardware, realising a great profit and all in the name of diplomacy.

On 4 May 1982, Argentine air attacks from Super Etendard fighter planes using Exocet air-to-surface missiles sinks the British Destroyer HMS ‘Sheffield’, with twenty men on board. One British Harrier plane is shot down.

On 7 May 1982, UN enters peace negotiations.

On 21 May 1982, the British HMS ‘Ardent’ is sunk by an Argentine air attack. Nine Argentine aircraft shot down.

On 23 May 1982, the British HMS ‘Antelope’ is attacked and sinks after an unexploded bomb detonates. Exocet missiles used.

On 25 May 1982 HMS ‘Coventry’ is hit by three 1,000 lb. air bombs dropped from Argentine Skyhawks; 19 British dead. MV ‘Atlantic Conveyor’ is hit by an Exocet missile and sinks three days later, 12 more British dead.

On 4 June 1982, Britain vetoes Panamanian-Spanish ceasefire resolution in the UN Security Council.

On 8 June 1982, an Argentine air attack on British landing craft Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram at Port Pleasant, south of Bluff Cove. 53 British are killed.

On 12 June 1982, the Cruiser HMS ‘Glamorgan’ is hit by an Exocet missile as it was bombarding onshore Argentine position. 13 British die. The Argentine junta have exhausted their stock of Exocet missiles. But more are expected and paid for by a reliable source and fellow Mason to Argentine President General Leopoldo Galtieri, his name was Roberto Calvi.

On 15 June 1982, Roberto Calvi arrived in London, at Gatwick Airport, from Innsbruck. It was his intention to give orders to Midland Bank plc, the correspondents of his Banco Ambrosiano, to affect several transfers to companies in Panama and the Bahamas with ultimate French ownership. A transfer was also destined to several accounts in France, and Banque Nationale De Paris and, Credit Lyonnais and, Liechtenstein. The beneficiaries of those accounts the British Security Services found to be the French manufacturers of Exocet!

EEC sanctions had been imposed upon Argentina but not upon Banco Ambrosiano and certainly not upon Roberto Calvi. The Argentine Government needed the missiles and the French were only too willing to dupe them, or so they later stated, but in the meantime, the money transfers would assist the French and they could either deliver the hardware or simply keep the money. Roberto Calvi, with his gargantuan commission from the deal, would be saved – for a while. Or, so he thought. All the information he required was contained in his briefcase. All the details of the transfers and all the citations of each transfer. The mystery of the briefcase was not about the Vatican, the Mafia, ENI, but accurately recorded bank details of the transfers to be effected.

Roberto Calvi came to London and planned a properly executed mission. He arrived on Tuesday 15 June 1982, allowing himself the weekend abroad to deal with his other business. He was not aware that the British Security Services had already been notified of his presence and his arrival. He wanted, needed, to be in London during a full banking week.

How did Argentina, though, pay Roberto Calvi to be able to effect payment in 1982, when Argentina badly needed the Exocet missile?

Calvi had formed in 1977, Ambrosiano Group Banco Commercial, which was a banking subsidiary in Nicaragua. In 1979, when the Somoza family had all but lost control of Nicaragua, Calvi liquidated the said Bank and placed all the assets in a new Bank called Banco Ambrosiano Andino, and it received in 1979, the sum of $60 million. That money was from the Argentine Government. In January 1982, a further $11,800,000 was deposited into Banco Ambrosiano Andino. The problem that Calvi faced, however, was that the money placed by the Argentine Government which was for them, in 1979, a perfectly genuine transaction was almost no longer available. In 1982, when the Argentine Government made a number of other deposits to effect payment for the military hardware already ordered and Exocet missiles, Calvi was in essence short of money and was not able to affect any payment.

The Argentine Government, however, were not to know of such and, up to May 1982, via a Panama company called Belrosa, a Liechtenstein company called Nordeurope and two other companies, called Erin from Panama and Manic, the sum of $258 million made Banco Ambrosiano Andino more than liquid and its correspondent bankers in London were the Midland Bank plc.

On 18 June 1982, the balance of cash at Banco Ambrosiano Andino was $338 million, and the Argentine Government had all but surrendered because, while the transfers had been affected, it required 48 hours to convert the money from US Dollars to French Francs, which was the currency of payment. Calvi arrived in London on 15 June 1982, an expert banker, having forgotten that ‘spot forex transactions’ require a 48-hour settlement.

Argentina had no time. Some of the military hardware was sitting in Panama, some in Nicaragua, and some in Chile! So much for General Pinochet having stated that he helped the British during the Falklands war.

The British Security Services were well aware that Pinochet was ‘sleeping half the night in one bed and the other half in another’, in the words of Stella Rimington during the Falklands War, and that he was ready to deliver military hardware which the French had delivered to Chile for Argentina. The defence of the French was that they delivered certain military hardware just prior to EEC sanctions being imposed.

When it came to the arrest of Pinochet in the United Kingdom on a warrant from Spain, there was no sympathy coming from the British Security Services. Margaret Thatcher had been told by the Security Services about Pinochet but in her ‘iron maiden’ style simply chose to ignore such and refused to believe it. Many years’ later surveillance photos were shown to her when she supported Pinochet at the time of his arrest. Again, she refused to believe the intelligence.

On 15 June 1982, Roberto Calvi telephoned several Banks, including the Midland Bank plc. He also called Banco de la Nacion in Lima and Banco de la Provincia of Buenos Aires, where contacts were relayed regarding the situation of payments on behalf of the Argentine Government who had paid over $300 million in a three-year period and now required action. There would be no action, just death.

It was not the Argentine Government that murdered Calvi, although, without doubt, they would have, and certainly shed no tear when they heard he had died. Galtieri heard on 19 June 1982, via BBC World Radio, but by that time he had lost the War.

The pressing of a button for a SWIFT transfer, which stands for Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, by the Midland Bank, or any bank for that matter, thus allowing the release of desperately needed military hardware for Argentina, would have meant that Britain risked losing the Falklands War, and history might have been re-written.

The British Security Services were well aware of the situation and had been watching Roberto Calvi who had banked that any transaction was best carried out right on the doorstep of the British and that any orders for money payments to another EEC country would not draw attention. Or so he thought.

The decision by the British Security Services to murder Calvi was taken on 16 June 1982 and carried out on 17 June 1982. The British could, without any problem, delay or defray money transfers from a British Bank in London, but could they risk that Calvi would send some secret message to another Bank in another country, or simply that he would escape Britain and find another way of making payment for Argentina for military hardware that had been pre-ordered and paid for and Calvi was holding the money?

The risk was simply too great!

The order came from the highest level. Only a handful was chosen to know and the deed was carried out on 17 June 1982. Calvi was killed by ‘State Order’. Whilst a negotiated peace was agreed on 14 June 1982, the Falklands ‘undeclared’ War ended officially on 20 June 1982, and General Galtieri deposed on 29 June 1982.

Roberto Calvi was killed in the line of duty. Those that gave the order to kill are now aged, ennobled, or dead. Those that knew – some are still alive and watching!

Giovanni Di Stefano

©giovannidistefano2010

NB: Some images retrieved from Google, will remove at owner’s request.

One thought on “The Roberto Calvi Story: A Case of Murder By State Order – Giovanni Di Stefano”