In May 1961, after a trial that was held mostly ‘in-camera,’ George Blake was convicted on five counts under s.1 of the Official Secrets Act 1911. Under normal circumstances, the maximum sentence permitted by law would be 14 years. The Lord Chief Justice Parker, however, ruled that each count to which he was convicted would be sentenced consecutively. As a consequence, his sentence was then the longest ever imposed: – 42 years.

There was no parole system at that time, but with the change in legislation the Criminal Justice Act 1967, which came into force in 1968, would have given Blake the opportunity of release at the one-third stage of his sentence. Therefore, he could have been released in 1975.

Instead, he ‘chose’ to escape from Wormwood Scrubs Prison in 1966.

George Blake was a spy for the Soviet Union during the 1950s. Blake was caught when a Polish spy who had defected to the West blew his cover to the CIA.

Blake was born in Rotterdam, on 11 November 1922. He had a Dutch mother and a Turkish father and was born George Behar. His father, Albert, was a naturalised British subject and proud of it. He had fought against the Ottoman Empire in World War I and had been awarded medals for his gallantry. In 1936, Albert died and George was sent to Egypt to stay with relatives. While in Egypt he continued with his English way of life by attending the English School in Cairo. He became close to his Uncle Henri who was to become a leading member of the Communist Party of Egypt.

During World War II, Blake returned to the Netherlands where he joined the resistance movement working as a runner. He was interned but released because he was not yet eighteen. Blake was certain that he would have been interned again once he reached his eighteenth birthday. He, therefore, escaped to the UK. When in England he changed his surname to Blake and joined the (SOE). Blake spoke several European languages with a degree of fluency. He acted as a guide for agents who worked in the Netherlands. Blake also translated documents brought back to the UK by agents who had worked undercover in Occupied Europe.

At the end of World War II, Blake was sent to Hamburg to interrogate German U Boat Captains. A talented linguist, Blake caught the eye of MI6. He was taught Russian and recruited by MI6 in 1948. His first posting was to Seoul, where he was tasked with creating a network of agents who were loyal to the West, and who also had a hatred of communism. His appointment was ‘specifically’ approved by the then Head of the SIS Sir Stewart Menzies.

However, the sudden invasion of South Korea by North Korea in 1950 led to the fall of Seoul. Blake was captured by the North Koreans and spent three years in detention. It was during this time in detention that Blake ‘converted’ to communism. He claimed that the writings of Karl Marx left a deep impact on him. In an interview many years after the Korean War, also, stated that it was the knowledge that defenceless Korean citizens were being bombed by the US, that, also, convinced him that the communist system had to be better.

In 1953, Blake was released and returned to the UK. He continued his work for MI6 working in Y Section, and in 1955 was sent to Berlin to recruit Soviet officers who were to work as double agents. However, his placement by MI6 gave Blake the perfect cover to contact the KGB. Blake ‘gave’ the KGB the names of about 400 agents who were working for MI6 and effectively sealed their fate. His mentor was still the Head of the SIS Sir Stewart Menzies. Whether Blake actually ‘gave’ the name of anyone to the KGB is a matter of fabrication.

In 1959, Blake returned to the UK and worked in a unit called DP4. This unit recruited British businessmen who travelled to the USSR, and also Russian diplomats based in the UK. By this time, his mentor had retired, and instead, the head of SIS was Sir Richard ‘Dicky’ White, a David Niven look-a-like who would stay in office until 1968, by which time Blake was well harboured in the USSR.

His ‘official’ escape from prison came out only some 22 years after the event when the SIS was under the guardianship of Chris Curwen, Cambridge educated and an ex-army officer from the Queens Own Hussars as he liked to tell all that would listen.

In 1966 Prime Minister Harold Wilson ordered a ‘D’ Notice on the whole saga, and despite a number of so-called enquires all was very ‘hush hush,’ as one would expect when a major spy miraculously escapes from a top security jail.

For many years it was the most talked-about ‘D’ Notice event with papers only made available in 2008 surrounding the matter.

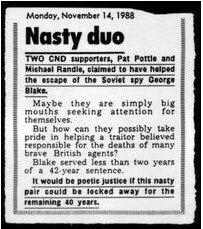

The story years later, when the press could no longer be contained and with Margaret Thatcher doing her best to smash the so-called Iron Curtain down, a story had to be found.

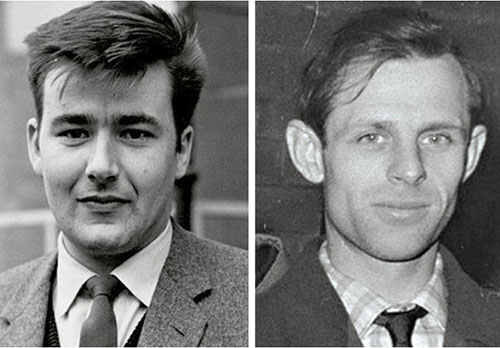

Enter, Michael Randle and Pat Pottle who were founder members of the Committee of 100 anti-nuclear direct-action group, and described themselves as libertarians and ‘quasi-anarchists.’ In 1962, at the height of the Cold War, they had both been sentenced to 18 months imprisonment for conspiracy to organise the Committee of 100 demonstrations at the nuclear base USAF Wethersfield in Essex. They both had first-hand experience of prison and it was their outrage at the ‘vicious’ sentence imposed on Blake that led them to attempt to free him. They believed the sentence was ‘unjust’ and that ‘helping him was a decent human response.’

Being ex-cons in the same prison Blake was in, not only enabled them to empathise with Blake but also gave them contacts on the inside who could help with the escape. It also meant they had some knowledge of the layout of the prison and the level of security.

Randle and Pottle used their experience of direct action in planning the Blake escape. Pat Pottle said, “I was determined that if I was to get involved with the break it should not fail because of silly or obvious mistakes… If we were to be caught it should not be the result of inadequate planning.”

While in prison for the Wethersfield actions, they had met Blake and also Sean Bourke (serving 7 years for sending a bomb to a senior policeman), who plotted the escape with them. After their release, they kept in touch with the two long term prisoners and when Sean was staying in a half-way house, preparing for release from prison, he made contact with Randle and Pottle. He told them that Blake had appealed to him to help him escape, rather than spend the rest of his life in prison.

When the idea of escape was originally raised, Blake suggested that they contact the Russian Embassy for help. But from the beginning, Randle and Pottle ruled out any idea of dealing with the murderous Soviet Union. It was their liking for Blake personally and sympathy for his 42-year ‘death sentence’ which motivated them. As Michael Randle said: “It was to be an entirely unprofessional – almost one could say DIY – affair.”

Using a number of inmates, so the story goes (none of which ever came forward to corroborate the story) Sean Bourke even smuggled in a walkie talkie that would not be picked up by the police radio frequencies.

Their plan was as follows: D-block, where Blake was housed, was the block nearest to one wall of the prison. The prison blocks have large gothic windows at each end made up of a number of smaller panes of glass, divided by cast-iron struts. Blake was to make his exit from the prison landing through one of these windows. Removing two of the panes of glass and one of the struts would make a hole eighteen inches by twelve – just big enough to squeeze through. Blake had made himself a wooden frame of these exact dimensions, which he kept in his cell to practice squeezing through. From the window, Blake would be able to drop down into the yard.

The panes of glass were removed from the window, a couple of days before the day of the escape, and the iron cross-bar was broken, and then stuck back in place with tape, so, that it could be quickly removed when the time came.

They planned to make the escape attempt between 6 and 7 pm, on a Saturday evening, when most of the inmates and staff would be at the weekly prison film show. The only two screws on duty were normally watching television in a room without a clear line of sight to the window Blake would be exiting from.

Bourke would park a getaway car nearby and throw a specially designed rope ladder (the rungs were made of size 13 knitting needle – sufficiently light to be thrown but still strong enough to hold Blake’s weight) over the wall at a prearranged point. There were security patrols that went round the perimeter walls, but Bourke had timed them and reckoned there was enough of a gap for the escape between each circuit they made.

There was a watchman posted in the prison yard who would be able to see the escape, but they figured that if they moved quickly enough, Blake could be over the wall before the watchman had a chance to raise the alarm. And even when if this did happen, they would have a few minutes head-start on any pursuing prison officers.

The day before the escape they went over all the plans, then burnt their maps and notes (and of course the sheets of paper underneath their notes, to remove the possibility of impressions being traced on underlying pages).

On the night, the escape went more or less to plan apart from Blake breaking his wrist in the 20-foot drop down the other side of the prison wall – a danger that they had failed to consider in the planning.

The ready co-operation of lots of ‘normal’ people in the escape attempt was a key factor in its success. There were many outraged at Blake’s clearly politically-motivated sentence that were willing to help in small ways. For example, Randle and Pottle managed to find a sympathetic doctor who treated Blake’s broken wrist – no questions asked.

That is how the story was told.

But, what to do with Blake now that he was out? That was the dilemma the story had to solve and it had to be credible. The more outrageous the story the more credibility it receives. So, 22 years later the duo told of how they had planned to turn Blake into a black person. While hiding out in the safe house, Blake was instructed to take a medicine called meladinine, designed for the treatment of vitiligo, a disease which causes white spots to appear on the skin. By taking extra-large doses, and spending time under a sun lamp, Blake would be able to pass as an Arab, helped by his knowledge of Arabic, which he had studied in prison.

Randle and Pottle forged a prescription to get large doses of meladinine, destroying the equipment used to forge the prescription afterwards, and going in disguise to the pharmacy to buy it. However, Blake never actually took the meladinine because he was worried about the side effects – large doses can cause liver damage.

But the story was by no means complete, it still had some melodrama in order to ‘put to bed’ once and for all the mystery of the escape of George Blake.

So, the story continues. It all started to go wrong when the boisterously over-confident Sean Bourke became increasingly sketchy. He had talked about getting forged passports from ‘underworld contacts’ but it later turned out he had no idea how to go about doing this. The meladinine idea and the false passports were finally abandoned and they settled for smuggling Blake out of the country instead.

It started to go from bad to worse. Sean Bourke had originally bought a getaway car in his own name. When this was discovered he was ordered to sell the car and buy another one under a false name.

But, after Blake had been broken out and was holed up in the flat they had rented, it turned out that Bourke had lied to Randle and Pottle, and actually used the original car which was registered to him in the escape. This was soon found by the police and identified as the car used in the getaway.

The ‘safe’ house Bourke had rented for Blake to stay in turned out to be a bedsit with shared facilities and a landlady who came in to clean once a week – not suitable at all for an escaped convict.

It later turned out that unbeknownst to Randle and Pottle, Bourke had purposefully endangered the whole project by sending photos of himself to the newspapers, phoning the police and telling them the whereabouts of the getaway car, and sending a death threat to the cop he had originally been sent to prison for sending a bomb to.

You could not make this kind of narrative up but it was fascinating and exciting and it seemed to resolve a deep mystery.

But every story needed a conclusion and one of success and here came the ending. Due to the discovery of the car and the situation with the flat, Blake was moved through a series of ‘safe’ houses around London, mostly staying with friends of Randle and Pottles’. This proved to be almost as dodgy as staying in Sean Bourke’s’ bedsit. The wife of one friend who agreed to temporarily shelter Blake told her analyst all about it – because of course the analyst, ‘requires her to be completely frank and not to conceal anything from him.’ Needless to say, Blake was swiftly found somewhere else to stay.

The police were looking for Sean Bourke because of finding the getaway car, so, it was decided that he should also travel to the USSR to meet up with Blake, and stay there until he was able to safely return home to Ireland.

It was finally decided to smuggle Blake out in a camper van. Randle and Pottle got a friend with some knowledge of woodwork, to build a compartment into the camper van. Michael Randle took his family to East Berlin in the camper van – with Blake hidden underneath. The wholesome family and the children in the back of the van, cheerfully sitting on top of the most wanted man in Britain, easily fooled the few cops and customs officers who happened to look in the back of the van. They never told the children they were sitting on top of an escaped spy, and managed to keep the whole thing from them.

George Blake was thus successfully delivered to East Berlin in December 1966, the conclusion to one of the most successful and most notorious prison escapes ever.

In June 1991, some 25 years after the so-called event, Michael Randle and Pat Pottle stood trial at the Old Bailey for their part in the escape. They defended themselves in court, arguing that, while they in no way condoned Blake’s espionage activities for either side, they were right to help him because the forty-two-year sentence he received was inhuman and hypocritical. Despite a virtual direction from the judge to convict, the jury found them not guilty on all counts.

De jure and by virtue of the acquittal the story they told of the escape of George Blake cannot be accepted because if it is accepted then the jury ‘got it wrong’ and that cannot be. In fact, it is not because on the jury at their trial where two members of the SIS who ensured an acquittal.

In fairness, John Major, the then Prime Minister, sought to avoid a trial even asking Colin McColl the Oxford-educated then Head of the SIS and who knew Blake personally, to try and intervene. It was important, however, that a trial did take place was the advice of Sir Patrick Mayhew the Attorney General. It was necessary in order that a story be told so, that, innocent people would not be punished. John Major, Colin McColl, and Sir Patrick Mayhew agreed that SIS officers would serve on the jury at the trial of Randle and Pottle, and ensure acquittal. Both Randle and Pottle would subsequently be rewarded for their part in the wholly fabricated story.

The Judge trying the case would not be told, and in 1991, after the acquittal, Alliot J even considered referring the case to the Attorney General for what he deemed was a ‘perverse finding’ by the jury.

Pottle died on 1 October 2000 and Dr Randle prospers.

So, if that was not how George Blake escaped, what is the real truth behind the most celebrated escape.

George Blake did indeed leave Wormwood Scrubs Prison on the 22 October 1966. The bars of his cell was indeed cut, but by an order of the Governor of HMP Wormwood Scrubs Prison, a week prior to Blake departing the prison D Wing would be manned by only two prison officers during ‘association time’ and the total number of men in D Wing on 22 October 1966 was 318.

George Blake was ‘removed’ from Wormwood Scrubs Prison by a young ‘then’ SIS Officer who subsequently rose to great ranks with the initials RBD, who had been instructed by his chief Richard White to collect Blake and take him to Luton Airport.

This had been agreed by the then Prime Minister, Home Secretary, and with the knowledge of Richard Helms the then Director of the CIA.

Blake was flown the next day at 10.45 from Luton Airport on a 175 Brittania 102: -G-ANBO the 1300 miles to Leningrad where he was delivered to Vladimir Y. Semichastny the then Chairman of the KGB.

The plane did not return empty. Inside the aircraft, there were two US Military Officers that had been captured in Russia and two British MI6 agents. Blake had been traded for 4 spies from the West.

In Russia, all know that Blake escaped on the 23 October 1966 not the 22 October 1966 (http://russiapedia.rt.com/on-this-day/october-23/) that is what students are taught at school. That is the day, of course, he arrived in Russia. That was the day his escape was complete.

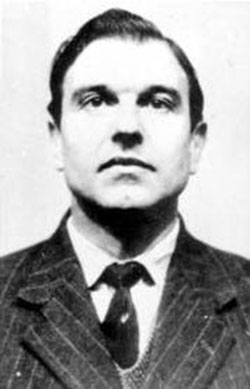

George Blake 2007

George Blake 2007

The rest is history.

Giovanni Di Stefano

Statement from GDS: George Blake RIP – those that count, know you were not a traitor to this country. Your real value only those in the know will appreciate.

Comment from GDS: 27 December 2020 @ 14:25 – Do you honestly think and believe that anybody serving that size of sentence could escape from a high-security prison if you do believe that you are suffering from spasms of aberrations.

Originally written and posted 8 March 2012, and now re-edited and published.

NB: Some images retrieved from Google, will remove at owner’s request.

Which do you believe?

I have my thoughts