OPC Global News and Media Corporation republish the factual story on how Dr Hawley Crippen was exhumed in the place of Sir Roger Casement.

A Human Rights Activist, Sir Roger Casement was an Irish Nationalist who attempted to smuggle arms into Ireland for the Easter Rising but was captured and executed.

Roger Casement

Roger Casement was born in County Dublin in September 1864. He joined the British Colonial Service and travelled to Africa and Brazil where he investigated the treatment of native workers. In 1911, Casement was knighted by King George V as Knight Bachelor for his efforts on behalf of the Amazonian Indians, before he retired from the service in 1912.

Casement helped form the Irish Volunteers with Eoin MacNeill in 1913. In September of 1914, in the light of the difficulties Britain was now facing in the war against Germany, Casement set out to gain support from Germany in the fight for Ireland’s independence.

In April 1916 he secured a supply of German ammunition and arms for the planned Easter Rising in Dublin. The arms were transported on a ship called the Aud while Casement followed in a submarine. The shipment was intercepted by British authorities and the crew scuttled the ship. When he was put ashore at Banna Beach in County Kerry he was arrested.

Richard Weisbach was the Captain of U-19 which brought Roger Casement to Ireland

Roger Casement was taken to England and was sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed on the 3rd August 1916. In 1965 his remains were exhumed and returned to Ireland. They were re-interred in Glasnevin Cemetery on the 1st March after a State Funeral.

That of course is the official version.

Casement’s bones, or what was left of them – he had been buried without a coffin in quicklime – were returned to Ireland by Harold Wilson’s government in February 1965. The first request had been made to Ramsay MacDonald’s government sometime between 1929 and 1931. This was refused, as were de Valera’s requests to Stanley Baldwin and Churchill, and Sean Lemass’s request to Harold Macmillan.

Discussions between the two governments about Casement’s body, and indeed Casement’s diaries, continued, which at times were somewhat heated.

The exhumation took place after dark in Pentonville Prison: Casement had, in fact, not been buried between two men called Kuhn and Robinson as had been originally believed, but beside Dr Crippen, according to the documents which the British officials had.

The lower jaw, eight ribs, several vertebrae, arm bones, shoulder bones, a number of smaller bones and the skull, virtually intact and still covered with bits of the shroud, were found and put into a coffin.

The bones, it was stated officially, belonged to a man of exceptional height – Casement was tall. The British paid for the coffin. (“It was a gesture which they felt they should make and were glad to make,” an Irish official said.) There was a State funeral in Dublin.

The coffin was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery beside others who had fought and suffered for the cause of Ireland: Daniel O’Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell, and Paddy Dignam.

It was a rather curious statement to make about the size of bones that would not be expected after an exhumation unless there was doubt and doubt there was.

Dr. Crippen was 5.3 at his best and thus, it was important that the Irish Government, that had pressed the British so hard, believe that the body buried without a coffin in quicklime be taken as that of Casement.

The location of the ‘grave’ of Roger Casement was prepared by J.G. Molloy of the Irish Embassy in London from ‘information’ given by Father James Carroll.

What did Harold Wilson know about the ‘switching’ of bodies? Could it be that Pentonville Prison simply made a mistake? Was it that Father James Carroll also made a mistake regarding the location?

The history behind the exhumation is of vital importance to understand what happened and why. One factor is, however, certain: –

Dr Hawley Crippen is indeed interred now in Dublin and Roger Casement almost went to Ohio in 2010 when an application was made by Studio Legale Internazionale to have ‘Crippen’s remains exhumed.

Originally, there was really no hope at all for Casement or anyone being exhumed. Such was the attitude of the British Government that their policy was for all convicted felons executed to remain on prison property. They wanted no shrines or martyrs.

Hopes for Roger Casement’s re-interment rose in 1939 with reports that Pentonville was to be demolished, but nothing happened before the outbreak of war which put the question in abeyance until the late 1940s, when the first Inter-Party government also made unsuccessful requests. Gertrude Parry died in 1950 and even de Valera seems to have become despondent by this time, telling one correspondent in July 1951 that as Casement’s body was buried in quicklime, it has to be disintegrated as to be completely indistinguishable from the rest of the grave. The Irish Ambassador in London, F.H. Boland, discussed the matter informally with Sir Perceval Liesching of the Commonwealth Relations Office (CRO) in 1952, but refused to give any information about the location of Casement’s grave.

However, an official at the Irish Embassy, J.G. Molloy, met Father James McCarroll, who had been Chaplain at Pentonville when Casement was there. Father McCarroll gave a description of the prison which Molloy wrote on a chart. He also told Molloy that Casement had been placed in the grave without a coffin and the body spread with quicklime.

Father James McCarroll circ. 1910

In September 1953 de Valera had a friendly lunch at 10 Downing Street with Winston Churchill and asked him to consider Casement’s re-interment. Churchill seemed sympathetic, but his reply clashed with de Valera’s hopes:

The law on the subject is specific and binding. No exception has ever been made to it, and there is no doubt that we should be led into great difficulties were we to seek to amend the law now. But apart from these legal considerations, I am sure that we should avoid the risk of reviving old controversies and reawakening the bitter memories of old differences.

De Valera was plainly unconvinced.

The lawyers here hold the opinion that the British law governing the matter is contained in Section 1 of your Treason Act of 1814, which gives the Crown absolute discretion as to the disposal of the body of the person executed. Your own first reaction was the natural and human one, and I am convinced – with a view to good relations between our two countries – the right one. So long as Roger Casement’s body remains within British prison walls, when he himself expressed the wish that it should be transferred to his native land, so long will there be public resentment here at what must appear to be, at least, the unseemly obduracy of the British Government.

In the spring of 1961, Lemass decided to make an approach to the British Prime Minister, Harold MacMillan. In a briefing memorandum, the Department of External Affairs noted that over the previous 20 years the reasons given by the British Government for not agreeing to reinterment had constantly shifted from non-legal reasons – controversy, public demonstrations – to legal – precedent, the need to amend the law, etc. There was also the problem of where the reburial would take place. Murlough would clearly be difficult, but Casement’s sister had selected a plot in Glasnevin cemetery, which was subsequently purchased by his American lawyer, Michael Francis Doyle. The important thing, in Doyle’s opinion, was that the remains be returned for burial in Irish soil. Lemass agreed and wrote to MacMillan on 18 April.

The passage of time has obviated the risks recrudescence of old controversies which led Mr Baldwin in 1936 to refuse the request then addressed to him; and the transfer of Casement’s remains would, I feel, be entirely in line with the better spirit which now characterises relations between the two countries.

MacMillan’s reply was regretful but firm.

The difficulties were still insuperable… The matter appears to me to be essentially one for a uniform rule; either no bodies should be handed over, or the relatives should in every case be given the option of removing the corpse of an executed person.

MacMillan went on to refer to the case of Timothy Evans, in which there was also pressure for exhumation and reburial.

This illustrates the impossibility of dealing with such issues in isolation. The Royal Commission on Capital Punishment … found that there would be serious objections to introducing a general departure from the existing practice in regard to the burial of persons executed in prisons.

Harold MacMillan

It was over two years before the subject was raised again. In September 1963, Con Cremin the Irish Ambassador in London discussed it with Sir Henry Lintott of the CRO, who once more raised the spectra of old controversies with the addition this time of possible objections from Northern Ireland. The issues were highly political he told Cremin and advised him to raise it directly with the Commonwealth Secretary, Duncan Sandys. With screaming newspaper headlines about sexual misconduct in high places, it was hardly the most opportune time to discuss Casement.

The following year, 1964, was Casement’s centenary and when Lemass met Duncan Sandys in London in March, he followed up the meeting with a letter, urging that a generous gesture by the British Government in Casement’s centenary year would be welcomed in Ireland. He also confirmed that a burial plot in Glasnevin was available for the remains.

It was three months before Sandys replied, referring to very great difficulties, the departure from precedent and the risk of reviving old controversies. He also mentioned problems with Northern Ireland:

If one result of returning the remains were to stimulate a campaign [for reburial in Northern Ireland] … it could well do more harm than good to our relations.

However, the tide was about to turn. Parliament dissolved and, in the October general election Labour was returned to power with Harold Wilson as Prime Minister. Wilson’s personal interest in Casement was to prove decisive. This was by no means clear to Irish ministers and officials at the time. Labour MPs had certainly been making promising noises about reinterment, but in the past these noises tended to fade when Labour was in government, with some exceptions.

Lemass wrote a long and eloquent letter to Wilson on 11 November 1964, pleading for Casement’s reinterment and promising “his readiness to cooperate in every way with a view to ensuring a very favourable reaction to a gesture by you directed towards solving this long-outstanding question which has been an unnecessary source of friction between our two countries.”

In a short reply, Wilson said the matter was being considered. Wilson always one for finding a solution discovered that if he granted the request, he could score valuable political points. Dick White, then head of MI6, came up with a solution in one of his many clandestine meetings with Wilson. “Give the Micks their Casement just the wrong Casement.” Wilson responded with some trepidation asking what the Director was saying. White made it clear “Give them Casement, just make sure it’s not Casement…Give them whoever is nearby. ‘Crippen’, give them ‘Crippen’. And don’t make it too easy.” As was his custom Richard White made meticulous notes of the conversation and placed them in the file and then placed a 100-year rule on the file.

Dick White

Two months later, on 14 January 1965, the Irish Ambassador in London, J.G. Molloy, was told the request would be granted. There were delays in January because of the lingering death of Winston Churchill, which did not occur until 24 January, and was followed by the State funeral.

However, from the evidence of a conversation between Paul Keating, Counsellor at the Irish Embassy in London, and J.D.B. Shaw of the CRO, it was clear there were still lingering doubts and reservations on the British side, especially in the Home Office. Of course, the Home Office knew nothing about the Wilson/White plan regarding Casement.

They wanted assurances, Keating was told, that Casement would be buried in Dublin and that there would be no unfriendly demonstrations. Wilson had told the Home Office that although the request would be granted it had to be made to look harder than it seemed.

They also wanted the transfer of the remains to be affected in utmost secrecy because of the ghoulish sensationalism of the Sunday papers. Those reasons, however, were clear. If the exhumation was carried out at night-which it was- it would be harder to detect which body was being exhumed.

Keating assured Shaw that his government would do everything to avoid embarrassment to the British authorities although the funeral would demand a certain amount of pomp and circumstance.

Shaw also told Keating that there would be no difficulty in identifying the grave, although how much would be left of the body was not known.

Keating said that even if little remained, the symbolic gesture was really what was important.

The correspondence between Lemass and Wilson on the formal transfer of the remains was kept private, although they both made statements in their respective Parliaments. In his letter to Lemass, Wilson stated that the grave could be identified, although the condition of the remains was unknown. “We hope that no questions would be raised as to their authenticity,” he stressed. Wilson was covering his back in case the Irish Government sought any formal scientific identification. In any case, Wilson had covered himself. He had made clear that the state of the body was unknown and in his usual manner hoped no one would question if it was really him.

Wilson also wanted assurances that there would be no difficulties with Casement’s surviving relatives. That of course was in case the relatives sought scientific assurances. If that happened of course it would be discovered that Casement’s body was in fact not his but that of Crippen.

Lemass assured him on both points.

On 21 February, two Irish officials, Sean Ronan, Assistant Secretary of the Department of External Affairs, and Andrew Ward, a principal officer at the Department of Justice, went to London to arrange the transfer of the remains. Strict secrecy was the order of the day. Ronan later wrote a remarkable report on the events of the next two days, which was occasionally macabre, often moving, and a fitting final chapter to the long saga.

On the morning of 22 February, he, Ward and Keating met a phalanx of British officialdom at the Home Office. They offered to put them in touch with a discreet undertaker, who would be able to cope with such a delicate task. The offer was accepted. The location of the grave had been identified, and the exhumation would be done by prison officers. It was estimated that since the body was buried at a depth of about ten feet, exhumation would take 6-8 hours. The Irish officials expressed a wish to be present at all stages of the exhumation as at any time we might be called upon to testify as to certain facts.

It was also hoped that the Catholic Chaplain at the prison could be present. This was agreed.

The exhumation was to take place after dark because of the risk that it might be seen by prisoners. Afterwards, the coffin would be placed overnight in the prison chapel.

After this meeting, Ronan and Ward went to see the phlegmatic undertaker recommended by the Home Office. They settled on the make and finish of the coffin. Later that afternoon, before leaving the Embassy for Pentonville, Ronan and Ward were surprised to receive a phone call asking them to call back at the Home Office. They met the Permanent Under-Secretary, Sir Charles Cunningham, and the Assistant Under-Secretary, H.B. Wilson. Cunningham asked what would happen if no remains were found. Since this question was hypothetical, Ronan and Ward did not give a direct answer as it might have affected the diligence with which the prison authorities would search for the remains. They also had private information that the quicklime might not have destroyed the skeleton.

Cunningham then referred to possible repercussions in Northern Ireland, but Ronan and Ward did not think these likely. The meeting then concluded with a surprising offer. The Home Secretary, Sir Frank Soskice, was anxious to pay for the coffin: it was a gesture which they felt they should make and were glad to make. The offer was accepted with appreciation.

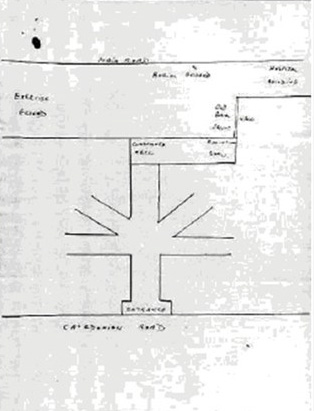

Layout of Pentonville Prison

Exhumation began at 4.50pm that afternoon. Ronan, Ward and Keating were present, as were six prison officers who were to do the digging, and a number of other officials from the prison and the Home Office. At one point, there were fifteen people standing by the grave. The weather was cloudy, cold, and damp, with snowflakes and rain. The burial ground was illuminated with two high-power lamps on stands, and there was a brazier to provide some warmth for the huddled group. The location of the grave, as Ronan noted with interest, tallied generally with de Valera’s recollections in June 1917, when he was detained at Pentonville.

He, Ward and Keating inspected documents produced by Home Office Officials, which identified the various graves.

The work proceeded at the rate of about two feet per hour, with the prison officers working in half-hour shifts. After 2 ½ hours, the grave began to fill with water, the result of a damaged culvert, and the exhumation became progressively more arduous and unpleasant.

Shortly after 8pm the first bones were dug up and at this point it was noticed that a prisoner was covertly observing the proceedings through a mirror reflected in his cell. The Deputy Governor of the prison immediately left to warn him off. A substantial part of the skeleton was finally recovered, to the considerable relief of Sir Charles Cunningham who was standing by at the Home Office in case nothing was retrieved. The bones consisted of the lower jaw, eight ribs, several vertebrae, arm bones, shoulder bones, a number of smaller bones and the skull, virtually intact and still covered with bits of the shroud.

By 10.20pm it was apparent that no more bones would be recovered, and the exhumation was terminated.

And so ‘Casement’ was taken to Dublin where he received a state funeral and his grave a shrine. The only problem of course was that both Harold Wilson and Richard ‘Dick’ White (sometimes called “Chalky”) sniggered at their frequent meetings as to how Crippen had turned himself into Casement, both names beginning with C.

Dr Crippen executed and buried at Pentonville Prison

At the end of 2008 a group of scientists carried out detailed DNA research and came to the unquestionable conclusion that Crippen could not have killed his wife because the remains at the house where Crippen is said to have buried his wife were those of a male and not female.

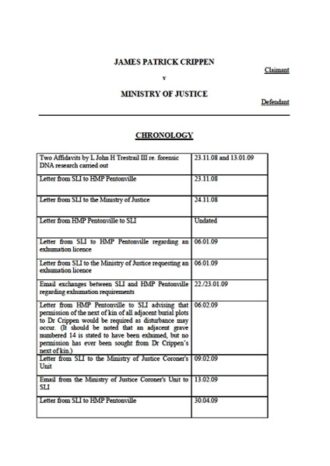

In early 2009 Giovanni Di Stefano – better known as the ‘Devil’s Advocate’ – was approached by a relative of Dr Crippen to exhume to body of Crippen and to have the remains taken to the family plot in the United States.

Giovanni Di Stefano the ‘Real Devil’s Advocate’

When all seemed to be going according to plan and the Prison Authorities and the Home Office had virtually agreed to the exhumation, then, after The Sunday Mirror in London ran a story about letters from Crippen’s lover that were buried in the coffin, did the Home Office realise that years back Crippen had been exhumed in place of Casement.

Di Stefano took the case to the High Court, but a Judge ruled that the Home Secretary had absolute discretion and, thus, no exhumation.

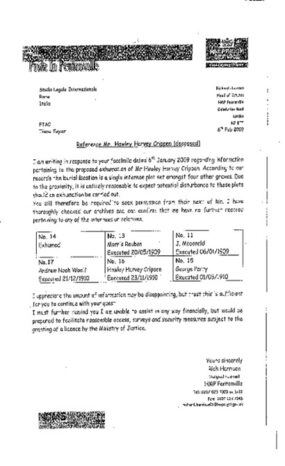

In a letter addressed to Studio Legale Internazionale dated 6th February 2009, Pentonville Prison exhibits the place where “Crippen” is buried, and it is easy to note that Plot 14 is marked ‘exhumed’ and missing is of course Plot 12.

Was Crippen actually in Plot 14, or in the undisclosed Plot 12?

Are the remains of Sir Roger Casement actually in Plot.16?

The discrepancy was brought to the attention of the Home Secretary by Martin Brunt in his report for Sky News on the 9th of March 2010.

The dilemma caused a massive stir at the Home Office when the file was examined. Brunt and Di Stefano were expecting to find love letters written by Crippen’s lover in the coffin, as authorised personally by Sir Winston Churchill.

Sky News had even contacted the prison service and wanted to film the exhumation. Of course, when it would be discovered that no ‘love letters’ existed then all would know that this was not Crippen and the lurking doubts that have always been there regarding the exhumation of Casement would be confirmed.

And so, yet again, an innocent Dr. Crippen would have to be sacrificed in the name of politics. Casement remains in Plot. 16 and Dr Crippen has been revered by all and sundry in Dublin.

It may well have been the justice Crippen had sought all along.

Published in the Daily Mirror 3 December 2012

© 2011 – Gdistefano

First published 2011 and then 31 July 2013