For the past seventy years but closer to a century Winston Churchill is known as the saviour of the modern world. He was the man who fought Nazi Germany and won.

Without doubt, the darling of British, if not world politics and a man bestowed the honour of a State Funeral. He was, doubtless, most of those and probably more, including a murderer.

Had Hitler won the war he would undoubtedly have tried Churchill for ‘war crimes’ but it was not to be. He escaped the indictments that Herr Hitler would have proffered and escaped three other accusations that only now can be made told. Churchill, according to new research, can now be accused of three murders: his mother Lady Randolph Churchill between the days 11-29th June 1921; Spymaster and the first head of the British Secret Service George M. Smith-Cumming at his house, 1 Melbury Road, Kensington, on the 14 June 1923; and T.E. Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia, between 13 and 19 May 1935.

There is no question of Churchill killing with his own hands he was far too careful and squeamish for such acts. He was the ‘mandate’, the man who gave the orders to kill and, as such, is equally guilty as those that carried out his orders. These were not political murders by the State but the acts of a man hell-bent on revenge, on his mother having cheated him out of his inheritance, and then ensuring he would not be caught and as a consequence disgrace the name he carried. He did this by killing the two men that knew what he did in 1921.

For Churchill silence was indeed golden and by further simply airbrushing his far more talented brother Jack Churchill from history, he became the ‘it’ man of the last century.

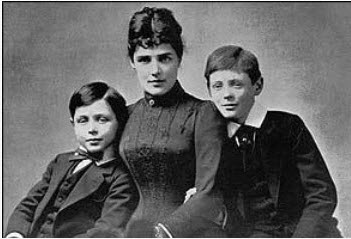

It is no secret that young Winston had little to no love for his parents. Lord Randolph was a neglectful father because of his stressful political career and his Victorian attitudes towards child-rearing. It has even been claimed that he positively disliked his children, who were 20 and 14 when he died, aged 45, in 1895, supposedly from syphilis. There is far more evidence, however, that Lord Randolph suffered from a brain tumour and that he had told his wife he had caught syphilis to avert any activity in the bedroom, especially, as he was well aware of her various affairs.

There was, however, considerable correspondence between Lord Randolph and both his sons, more so Winston, but he was a man that did not display his feelings. Was it that trend which ultimately cost his wife her life at the hands of Winston Churchill in 1921?

In fact, if anyone of the parents should be criticised it is his mother Jennie (née Jerome), an exuberant American socialite who, as evidence now revealed shows effectively, robbed her sons of some £16,800 of income that was rightfully theirs – the equivalent of about £1,500,000 today.

Lord Randolph had made his will in 1883, leaving his estate in a trust fund for the benefit of his wife during her lifetime and for his two sons and their children after her death. But he also inserted a clause that said if Jennie were to marry again, ‘his sons or their children should have access to the trust fund, in order to help his, or her, advancement in the world’.

It was this clause that, once Winston Churchill discovered, would cost Lady Randolph her life in a very spectacularly clever manner.

Lady Randolph, or Jennie as she preferred to be addressed, deceived her sons about the true nature of Lord Randolph’s will to fund her extravagant and hectic social life through a series of ruinously expensive loans. For years Winston and his brother Jack were led to believe that their father had left no provision for them in his will, except that they would inherit a small trust fund after the death of their mother. Jack longed for a career in the Army but was forced to become a partner in a city firm for financial reasons, and even had to delay his marriage to the beautiful Lady Gwendoline Bertie because he lacked the money to marry.

It was only in February 1914 that the truth was discovered. Wrestling with his mother’s chaotic finances as she divorced her second husband, George Cornwallis-West, a man as young as Winston, Jack took the opportunity to read his father’s will in detail and immediately relayed the contents to his brother Winston.

They were astonished to find that he and Winston could have claimed up to £600 a year each (around £50,000 today) from the trust fund since Jennie’s second marriage in 1900.

Jennie had systematically expropriated her children’s inheritance for 14 years. It was a cause of action that would cost her, her life at the hands of her eldest and by then famous son Winston.

On the advice of Winston, a letter was delivered to Lady Randolph written by Jack, but in reality, dictated by Winston. It was a letter of rebuke. Jack let her know how pained he was at her dishonesty: ‘We had always thought that Papa was very wrong in not making any provision for us during your life,’ he wrote. ‘It makes a considerable difference finding that Papa’s will was not made – as we were always led to suppose – carelessly and without any consideration for us. It is quite clear that he never thought that while you were single you would be unable to pay us an allowance, and the clause in the will covered the situation – which did actually arise – of your remarriage.’

Winston Churchill was very clever in ensuring he would leave no traces in a plot that would take him seven years to execute. When the chance arose, it was well planned and premeditated.

Winston Churchill loathed the way his mother was a spendaholic and always available to Edward, Prince of Wales. For many years Lord Randolph blamed the collapse of his marriage and his political aspirations at the door of the Prince of Wales. It was without doubt Lady Randolph was indeed one of his ‘favourites’ during the 1890s.

Shortly after Lord Randolph’s death until early 1898, the prince regularly visited Jennie at her house, 35a Great Cumberland Place, where she lived mostly alone. Winston was with his regiment in India; Jack was either at Harrow or living with a family in France to learn the language. ‘Tum Tum’, as Jennie called the 20-stone Prince, would send her billets-doux announcing that he would call at five ‘for tea’. He made particular reference to a geisha dress he wished her to wear for him, which apparently was a kimono that slipped off easily. Rumours of such a liaison reached, of course, the ears of Winston Churchill to his utter contempt and dislike.

Eventually, as is always the case, Lady Randolph finally found herself ousted as the prince’s ‘maîtresse en titre’ by the beautiful Alice Keppel, she sought solace by promptly seducing George Cornwallis-West, widely believed at the time to be the prince’s illegitimate son.

When Alice gave birth to a child by Edward, Jennie married George, a handsome man born in the same year as her elder son. It was to prove a happy match until he fell in love with the actress whom Mrs Patrick Campbell had ironically introduced as the leading lady in a play written by Lady Randolph.

Winston Churchill loathed the ‘arrangements’ as he called them and often lamented the situation to Mansfield George Smith, a then retired naval captain, who would become Churchill’s second victim. It was Churchill who comforted the then Smith-Cumming after his road accident that ended the life of Smith-Cumming’s son.

In 1914 Winston and Jack discovered the true treachery of their mother and the hatred for his mother grew.

Winston Churchill was always by his own admissions a rebel and a born maverick. He was not the brightest of students and he was certainly capable of ‘dastardly’ behaviour, both at school and whilst in the Army. In 1900, he was elected Conservative MP for Oldham but in 1904, he left the Conservative Party and joined the Liberal Party, which, he believed, better represented his economic views on free trade. From 1906 to 1908, he was a Liberal MP for northwest Manchester and from 1908 to 1922; he was, strangely enough, MP for Dundee.

Between 1908 and 1910, Winston Churchill held a cabinet post when Herbert Asquith, leader of the Liberal Party, appointed him President of the Board of Trade. Winston Churchill’s major achievement in this post was to establish labour exchanges.

In 1910, he was promoted to Home Secretary. As Home Secretary, Winston Churchill used troops to maintain law and order during a miners’ strike in South Wales. He also used a detachment of Scots Guards to assist police during a house siege in Sidney Street, East London, in January 1911. Whilst such actions may have marked him down as a man who would do his utmost to maintain law and order, there were those who criticised his use of the military for issues that the police usually dealt with. It was a similar trend that would lead to him committing three murders.

From October 1911 to May 1915, Winston Churchill was made First Lord of the Admiralty. In this post, he did a great deal to ensure that the navy was in a state to fight a war. Winston Churchill put a strong emphasis on modernisation, and he was an early supporter of using planes in combat. He was not afraid of risking lives as the Gallipoli campaign would prove and nor would he be afraid of taking lives.

Churchill was to pay the price for the bloody failure of the Dardanelles campaign in 1915 – it was Winston Churchill who proposed the expedition to the War Council and, as a result, he was held responsible for its failure and considerable loss of lives. He was dismissed from his post at the Admiralty, and he was made Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Having been Home Secretary and First Lord at the Admiralty, this was seen by many, including Winston Churchill, to be a demotion and he left the post after just six months.

Churchill re-joined the army. Here he commanded a battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front until May 1916. However, Winston Churchill quickly returned to government as taking lives for him proved no great trouble but risking his own was another matter.

In 1917 he was appointed Minister for Munitions – a post he held until 1918.

In 1919, Winston Churchill was appointed Minister for War and Air – a post he held until 1920.

In 1921, he was appointed Colonial Secretary – a post he held until he lost his seat for Dundee in the 1922 election.

Throughout this time all that lingered on his mind was the shameful conduct of his mother and, her third marriage and, countless affairs. Lady Randolph’s scandalous lifestyle fed many rumours and myths and those constantly reached the ears of Winston, in particular concerning her behaviour both before and during her marriage to Lord Randolph. One of the allegations that were circulating between 1916 and 1921 was whether Winston was illegitimate?

Worse, talk in the House of Commons referred to the widespread belief that Winston was born just seven months after the marriage. Given that such premature babies were unlikely to survive in 1874; his mother must have been pregnant at the time of her wedding.

When rumours, however, started reaching Winston that his brother Jack was not fathered by Lord Randolph it would seal the fate of Lady Randolph to one of murder.

His brother Jack’s health was precarious and early on a close family friend, John Strange Jocelyn, 5th Earl of Roden was called upon to stand as godfather. For this act of kindness, he would be routinely cited as Jack’s father.

In fact, he is only one of several men, other than Lord Randolph, rumoured to be the father, including the 7th Viscount Falmouth and Count Charles Kinsky. Would this be the reason why Winston would ultimately ‘airbrush’ his brother from his life?

Was this the final act that would lead to Winston committing matricide?

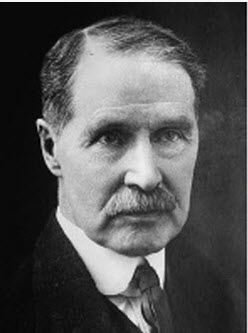

Sir George Mansfield Smith-Cumming was born on April fool’s Day 1859, the youngest son of 13 children, to an officer of the Royal Engineers. Strangely having been commissioned in the Royal Navy he suffered seasickness. He longed for a desk job and, for adventure and, in his own right was similar to Winston Churchill. He was by no means bright but clever in his own way. He was subject to hyperbole like Churchill and exaggerated his own importance.

When his son died in a car accident in 1914, the stories doing the rounds was that George amputated his own leg with a penknife to survive the accident. It was, of course, pure fantasy but it was this early ‘Walter Mitty’ life that, similar to Churchill, would lead to success and his appointment as the first Chief of what would become MI6.

He was known to Winston Churchill as their careers ran parallel and Churchill often complained to him of his poor finances. In 1909 Cumming was the de facto head of the new Secret Intelligence Bureau better known now as MI6. He also became acquainted with Lady Randolph Churchill who had confided to him about her precarious finances before Jack and Winston discovered they had been cheated out of their inheritance. Churchill instead complained to Cumming how his own political aspirations had been thwarted owing to lack of money and how disgraceful his mother was becoming in High London Society.

The keeper of secrets, as well as the State Secrets, would be the death sentence for Cumming only two years after Lady Randolph was murdered, and by the same hand.

There is no evidence that Lady Randolph ever shared intimate moments with Cumming as there is no evidence, she shared intimate moments with a host of other would-be suitors. What is clear, however, is that the relationship between Lady Randolph and Cumming as well as Cumming’s friendship with Churchill would become problematic.

Papers accumulated by Henry Winston (Peregrine) Churchill that have recently come to light show that for example, Lady Randolph left as part of her papers “Lady Randolph’s admittance card to the trial of Sir Roger Casement”. The admittance was authorised by Cumming.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Cumming was able to work with Vernon Kell as well as the Special Branch and directly responsible for the arrest of a number of German agents in the United Kingdom. One such was Sir Roger Casement who together with eleven others was executed for treason.

Casement was a British Consul and famous because of his exposing human rights abuses in the Congo and South America. He was, without doubt, an Irish Republican and tried to engage the Germans into helping a Free Ireland.

Winston Churchill’s grandfather, John Winston Spencer-Churchill, 7th Duke of Marlborough, was at one time the Viceroy of Ireland for four years and Winston’s mother was often in Ireland during Lord Randolph’s many absences abroad. Jennie was a political troublemaker and had Irish Republican sympathies. She was after all an American that was living through colonial independence.

Cumming had given Lady Randolph Churchill access to one of the most notorious trials, and because of the sensitivity of the evidence, only those who had a ‘special pass’ could attend. Cumming was directly responsible for the arrest of traitors and a special friend and confidante of both Lady Randolph and Winston granted ‘Jennie’ the concession.

By 1916 both Winston and Lady Randolph had confided to Cumming their position. Winston at the considerable pain and displeasure it was that his mother had stolen his inheritance and a ‘wayward woman’ and Lady Randolph’s ever questing for more money.

Once Winston discovered in 1923 that Cumming knew about his mother’s misappropriation of funds and that Cumming had invariably ‘ran with the hare and hound’, it signalled murder number two for Winston Churchill.

Thomas Edward Lawrence better known as T.E. Lawrence or Lawrence of Arabia was a close friend of Churchill and who was instrumental in the division of the Middle East in February 1921 where he found Churchill an easy person to talk to and confide in.

Lawrence told Churchill during their various breaks what had happened to him whilst he was captured by the Turks, and Churchill confided to him the inner secret of loathing his mother, everything she stood for and was overheard in the hotel bar saying, ‘At times I wish she was dead, I wish it so.’

Similar to Cumming and Churchill, T E Lawrence was also a dreamer and maverick. After the First World War, Churchill was Colonial Secretary and had to make a new and more just settlement in the Middle East. He was determined to assemble the best and brightest of Britain’s Middle East experts. Despite Lawrence’s ‘maverick’ reputation, Churchill could not overlook his vast knowledge of the Arabs and their needs.

Churchill persuaded, through friendship and confidences shared, Lawrence back into public service in 1921 with a special post in the colonial office. Lawrence had enormous respect for Churchill and genuinely believed they could repair the injury done to the Arabs at the Paris Peace Conference, stabilize the region, and remove British armed forces.

But Lawrence also knew the secret loathing that Churchill had for his mother and the doubts he raised over his brother Jacks’ paternity.

Confidences were easy for Lawrence and the question of paternity was not so strange to him. The bond between Lawrence and Churchill was one with ease. Lawrence was born in Tremadog, Wales, in 1888, Thomas Edward – known as Ned – was the second of five illegitimate boys. Lawrence’s father, Sir Thomas Chapman, left his first marriage when he fell in love with the family governess, Sarah Junner. His parents assumed the name of Lawrence and remained unmarried.

In Cairo at the Semiramis Hotel, both Lawrence and Churchill exchanged their fears, hopes, ambitions and deep-rooted hatred for what both deemed to be injustices of life.

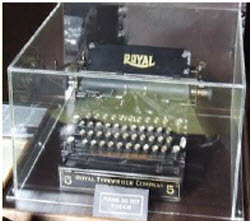

Lawrence was well aware in February 1921 at the Cairo Conference that Churchill hated his mother and wanted her dead. Churchill knew the secrets of Lawrence and what happened to him at the hands, and other parts, of the Turks when he was captured and tortured. This would be the cause of the third Churchill murder in 1935 when Lawrence was adding to his already published autobiography, ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’. The new manuscript contained accurate notes and, accounts kept by Lawrence and, written simultaneously in 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference and the 1921 Cairo Conference; it contained a whole new chapter on Winston Churchill.

That manuscript, in an abridged version and minus the important chapter, was published in 1997 when the copyright expired. Lawrence had not wanted to write anything further after 1926 and had made clear he would not be publishing his new manuscript. Yet, within weeks of his murder the abridged version was published, contrary to the instructions of Lawrence, minus the chapter on Churchill and their ‘confidential talk’.

The ‘offending’ and ‘revealing’ chapter manuscript is kept at MI6 Headquarters and no known copies are ‘believed’ to have been made. That belief is, however, only shared by the Security Services, because a copy was made in 1988.

Churchill remained in close contact with Lawrence right to the end of Lawrence’s life. Churchill headed the list of notable mourners. He said of Lawrence: ‘I fear, whatever our need, we shall never see his like again’.

His murder at the hands of Churchill would maintain the secret forever – or so Churchill thought.

At the outbreak of the First World War, August 4th, 1914, King Edward VII had died in May 1910, and King George V and Queen Mary were on the throne. Events in Lady Randolph’s life had also moved on, as also Winston. Her second husband George Cornwallis-West had run off with the famous actress, Mrs Patrick Campbell, and Jennie had divorced him. This further caused considerable humiliation for Winston and made him a laughingstock in his social circle.

But Lady Randolph had a new admirer a wealthy English landowner, Montague Porch, who was working for the Foreign Office in Nigeria. Lady Randolph’s’ two sons had both married in 1908, Jack, to Lady Gwendoline Bertie (Goonie), and Winston, to Clementine Hozier (Clemmie). The daughters-in-law called their mother-in-law ‘Belle-Mère’ (beautiful mother). Jack was a stockbroker and partner in the firm of Nelke Phillips in the City. Winston was an MP and at the Admiralty. It was around this time, at a time when Winston needed all his concentration, that he discovered his mother’s deceit.

Back in 1910, Churchill was then Home Secretary. One of the most controversial cases was the trial and execution of Dr Hawley Crippen, upon which Churchill took personal interest and whereupon he made a close friend of a young controversial pathologist, Dr Bernard Spilsbury.

Crippen was accused of murdering his wife and running off with his mistress Ethel Le Neve. They were caught on a steamship to Canada and eventually returned to England to face trial.

They were then brought separately to trial:

Crippen was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death; and Ethel Le Neve was found not guilty of being an accessory after the fact.

After Crippen’s appeal was turned down, a petition for clemency was rejected by Winston Churchill, who was then Home Secretary in a Liberal Government.

Churchill was kept regularly up to date on the case, which was accompanied by a mountain of paperwork. As well as answering questions in Parliament, Churchill also had to decide such important issues as to whether or not Le Neve should be allowed to kiss Crippen when she visited him in jail.

Crippen was executed on 23 November 1910. But, more importantly, Churchill was educated by Spilsbury on forensic science and modes of murder. It was unusual to see a Home Secretary befriend a prosecution witness but, in 1910, the Home Secretary had considerable powers which were beyond reproach.

At Crippen’s’ trial, Lord Alverstone stated to the jury, and so directed, that if the remains were those of a man, then Dr Crippen must walk from the dock. Dr Crippen was executed as the jury believed Dr Spilsbury, that the remains were those of Cora Crippen.

It was a surprise to all when Churchill refused any act of clemency and, it was said at the time, this was entirely owing to the undue influence placed on him by Spilsbury, who had much to lose if Crippen cheated the gallows.

Since 1910 Churchill had studied well – with the open assistance of Spilsbury – the art of murder, and more significantly, how to evade detection. By 1914, when he and his brother had discovered the fraud Lady Randolph had perpetrated upon them, and the numerous paramours of Lady Randolph, he would put all he had learned from the good Dr Spilsbury to good use, but he had to wait for his moment.

By 1914, Churchill’s greater priority was not his mother, but the War. Throughout the period, though the many mistakes Winston Churchill made that cost over one hundred thousand lives, he would blame his lack of clarity and concentration on his mother.

At that time, women were still not enfranchised, despite the protests of the suffragettes, and aristocratic women could not undertake paid work.

Lady Randolph’s first concern, however, was War work. She persuaded the wealthy Mr Paris Singer, of the famous sewing machine company, to offer his residence, Oldway Mansion, Paignton, in Devon for use as a hospital. It was turned into a well-equipped, 255-bed hospital, which included an operating room. Throwing herself into raising money for the American Women’s War Relief Fund to finance the hospital, Lady Randolph became Chairman of the Executive Committee, with Paris Singer as Vice-Chairman. There was a staff of 151, which included 8 surgeons, 15 American nursing Sisters, 17 English nursing Sisters, and 21 Probationers. Wounded soldiers were transported to the hospital in troop trains. Patient intake included, in 1915, New Zealanders and wounded men from the Royal Inniskillings and the North Staffordshire Regiments; and in 1916, injured soldiers from the Somme offensive. By 1916, 3,203 cases had been admitted for treatment. The funds raised provided also, motor ambulances for the front, clothes for refugees, employment for women, and famine relief for Belgium.

Lady Randolph Churchill, throughout the war, was well trained as a nurse – training, however, that would not save her from her son in years to come.

Having formerly opposed votes for women and, on one occasion, told suffragettes publicly that they ‘ought to be forcibly fed with common sense’, Lady Randolph had matured politically, even if the male company she kept left much to be desired.

She also helped organise buffets at railroad stations for the thousands of travelling troops. Along with the famous opera singer, Maud, Lady Warrender, she set out on a series of morale-boosting concerts around the country. They toured the army camps and hospitals, entertaining the troops, with Jennie playing the piano, and Maud singing.

Lady Randolph also took up work for Lancaster Gate Hospital, in London. She kept the wounded men cheerful and wrote letters for them to their wives and sweethearts. She worked tirelessly and raised funds and was promoted to Head Matron. This would not help her when she was at her most vulnerable.

Much to the dismay and disapproval of Winston, she married for the third time, to Montagu Phippen Porch, on June 1st, 1918.

Winston was livid with anger and yet further humiliation at a time when he needed to advance his career. Ever since the Crippen trial, Churchill had maintained close links and a friendship with the chief prosecution witness, forensic pathologist Bernard Spilsbury. Churchill now simply had to wait and bide his time for an opportunity.

Women over the age of 30 were finally granted the vote at the end of the War in 1918, but women over the age of 21 were not enfranchised until 1928. In May 1921, Lady Randolph went to spend the weekend with a friend, Frances, Lady Horner at Mells Manor, Somerset. She heard the dinner gong and, fearing she might be late, rushed down the stairs, tripped, fell and broke her ankle. A local doctor set it, and Lady Randolph returned home to London in an ambulance. A nurse cared for her, but gangrene set in, and a London surgeon amputated her leg. The story goes that she was very brave and told him to ‘be sure and cut high enough’.

Convalescing at home, she suffered a sudden haemorrhage on the morning of 29th June 1921. She slipped into unconsciousness from which she never awoke. Winston and Jack and, other family members and, friends remained by her bedside as she slipped away.

That is the story told by Winston Churchill. The truth is much different, according to research and documents that finally can be revealed.

Some ten years previous, Lady Randolph had indeed sprained her left ankle whilst frolicking with her second husband at Salisbury Hall, their residence.

On this occasion, Lady Randolph did indeed fall and, by a mere accident, allowed Winston Churchill the opportunity he had been waiting to rid himself of what he called his ‘embarrassment.’

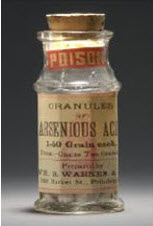

Forever an opportunist, Churchill was dining with Spilsbury on 28th May 1921, when he mentioned his mother had fallen and broken her ankle. Spilsbury, jokingly, replied he hoped that it would not turn to gangrene, as that would be dangerous.

Over 1 million people sprain or break their ankle in the US each year, yet not a single case of gangrene has ever been reported. The probabilities of gangrene caused by a sprained ankle are remote.

Just how, then, did Lady Randolph die? The truth is that she was murdered in an opportunistic manner.

Lady Randolph, by pure accident, did fall as a result of new Italian high heeled shoes she was wearing. Winston Churchill was not responsible for that. He simply used an accident to plan and perpetrate a murder.

On 10th June 1921, a London surgeon from Paddington Hospital did indeed amputate the leg of Lady Randolph. It is important at this point to know that Dr Spilsbury had studied, and was indeed based, at the same hospital where Lady Randolph was operated.

The decision to operate was preceded by a meeting between Winston Churchill, Dr Spilsbury and the head of the Security Services, Smith-Cumming, and, at that meeting, Churchill made clear to his three friends his desires and wishes. By 1921, Spilsbury had become quite famous, but Churchill reminded him of Crippen, and Churchill was well aware that the testimony Spilsbury had given at Crippen’s trial that he was sure the remains found at the house were of a female, was erroneous.

Churchill had saved the reputation of Spilsbury, costing Crippen his life. It was now time for a favour to be returned.

On 10th June 1921, meeting his brother Jack and facing a decision to amputate his mother’s leg, the conversation recorded showed that Jack had said in a worried tone ‘Gangrene – but I thought it was a simple break.’ Winston replied, ‘These things do happen.’ Jack emphasised ‘But it was a simple break.’ Winston was the elder brother and his decision carried with the words ‘It is to be amputated the sooner the better.’

That was the death sentence for Lady Randolph Churchill.

To show his complete disdain and contempt for his mother during her ‘illness’ one would imagine that Churchill would show concern, attend her, or take extra care. Between May 28th, 1921, and 10th June 1921, Churchill made over 39 speeches in the House of Commons. Between 10th June 1921 and 29th June 1921, he made 31 speeches and, on 29th June 1921, recorded in the security archives are two letters from Churchill to Prime Minister Lloyd George to be excused from the Anglo-Irish Conference. One letter asks to be excused that day for the funeral of his mother and the other because of the death of his mother. One letter was from the Colonial Office, and the other from his residence of 2 Sussex Square, London W2.

Spilsbury had made sure his colleague, who performed the surgery, would indeed cut well above the knee. Doing so would ensure healing would take longer, and the risk of haemorrhage would be greater.

It was Spilsbury enhancing his friendship with Churchill to members of the hospital staff, who would suggest Lady Randolph be discharged from hospital as soon as possible. As it was, she was indeed discharged to her home at 8 Westbourne Street, Paddington, within a miraculous three days.

It was Spilsbury who arranged a hand-picked nurse, about whom friends of Lady Randolph would subsequently comment that ‘she spent more time trying on Jennie’s clothes and Chanel perfume than nursing’.

It was Spilsbury who would recommend the ‘new therapy’ that, allowing oxygen into the wound would alleviate any gangrene that was left post-amputation, and thus he instructed his hand-picked nurse to keep Lady Randolph’s bandages as loose as possible and, not to change them for as long as possible.

Lady Randolph was prescribed sedatives that kept her subdued so that she was not at all aware of what was happening. In all this period, Winston Churchill never once attended his mother, arriving only late on 29th June 1921, and he gave strict orders not to contact Montague Porch, his mother’s by then third husband, who was in Nigeria.

Oxygen, being toxic to gangrene, a fact of which Spilsbury was well aware, and maintaining loose bandages that were not changed, would accelerate death. When it finally arrived, it must have been a relief to Lady Randolph, who would have died painfully.

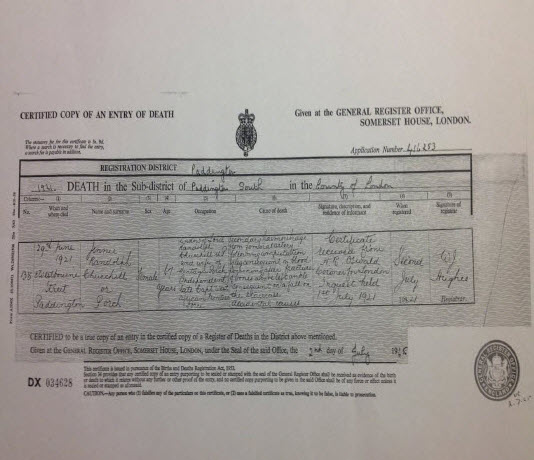

The nurse, who had been present since 13th June 1921, disappeared. On Friday, 1st July 1921, a Coroner’s Inquest was held at Paddington, with a death certificate signed on the following day after the Inquest – a procedure somewhat irregular.

Amongst papers recently discovered is the original death certificate. The cause of death according to the certificate is cited as: ‘Secondary haemorrhage femoral artery following amputation of leg consequent on blood poisoning after the fracturing of bones above left ankle consequent on a fall on the staircase accidental causes’.

The death certificate says nothing at all about gangrene, only blood poisoning. But Winston Churchill knew this and allowed the myth of gangrene to be advanced, to ensure Spilsbury and he would not be detected.

What is known is that, upon Lady Randolph’s return to London on 3rd June 1921, Spilsbury was a visitor to the house. As a doctor he examined Lady Randolph, who was a regular visitor to the Central Criminal Court, and, after Lady Randolph had complained of pain, he gave her an injection. The needle contained bacteria from his laboratory, whilst the fluid was indeed a sedative.

History has not been kind to Sir Bernard Spilsbury. Two of his four children died before him and, in 1947, when his conscience could take no more, and invariably thinking about the murder of Lady Randolph Churchill, he committed suicide by gassing himself.

In 1923, as a reward for murder, Churchill persuaded Prime Minister Andrew Bonar Law to award Dr Spilsbury a Knighthood – one earned in blood and by blackmail.

Having rid himself of what Churchill privately called his ‘embarrassment’, and evaded justice, his mission was now to silence those who knew.

It would be two years before Churchill would kill again and, once more, with his accomplice, Spilsbury.

Even on her death, Lady Randolph created more scandal for Winston Churchill. Black rimmed newspapers announced her death with the title ‘Lady Randy’ because it was said she had more than 200 lovers, the majority of which were considerably younger than her. Winston Churchill’s murder of his mother did not rid him of his ‘embarrassment’; it just permitted the tabloid press to attack Churchill through the morality of his mother. Jennie was dead but would never be forgotten. For now, Churchill had committed what he thought was a perfect crime. But for the very clear wording of the death certificate, Churchill would probably never have been exposed.

For the next few years, he paid the price of his mother’s morality by losing his seat in Parliament and out of politics. Whilst his mother was alive she was able to defend what reputation she had left. Dead she was fair game for the ever-growing scandal sheet papers. Churchill had simply not considered the consequences of his mother’s death, he merely wanted to be rid of the problem. It was this aspect of his character that made him an undetected murderer, but a man who would rid the World also of Nazi tyranny.

But first, he had to dispose of those he had shared his most inner and deepest thoughts.

Captain Sir George Mansfield Smith-Cumming KCMG, CB would not be so easy a target as Lady Randolph, and at the funeral of Winston’s mother, he made an appearance. It was there that he ‘let slip’ that Lady Randolph had confided in him her precarious financial problems. Winston Churchill had not been aware that Cumming was so close a friend of his mother, but he now understood that Cumming had, indeed, been running with the hare and the hounds.

There is some considerable controversy as to how the good Captain died, with one story that he suddenly collapsed at his office, and another contradictory version he died ‘suddenly at his home, 1 Melbury Road, Kensington, London, on 14 June 1923, shortly before he was due to retire.’

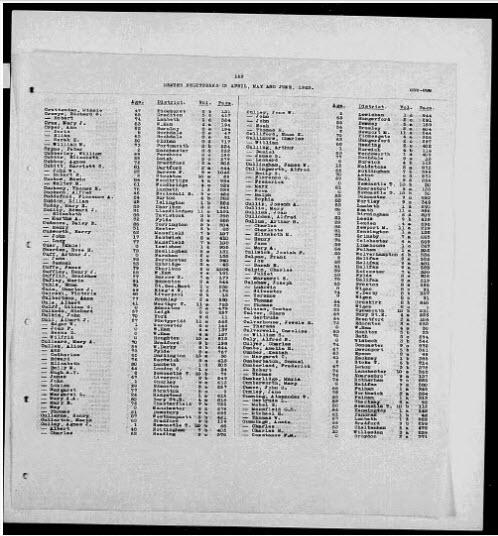

Searching the records for the first Chief of MI6 was not to be an easy task. Finally, what was clear was that many records were either misleading or simply false, if not confusing. The Official Registrar lists him as having been ‘registered’ dead in Kensington and not his MI6 office. So, just how did Cumming die?

What is known about Cumming is mostly legend, if not fable. He had by far exaggerated the threat of German spies in England before the War and it is he directly that caused the arrest, trial, and execution of many innocent people, both prior and during the First World War, including Sir Roger Casement.

Nevertheless, the result was a greatly aroused public at a time when Britain had no civilian organization to deal with the espionage threat, whatever its magnitude. Why was a civilian organization needed? The War Office had only one overtaxed civilian intelligence officer who ran agents in Europe, but couldn’t attachés and diplomats supplement his efforts?

Churchill had found his twin in Cumming as both were extreme opportunists with dark minds. Although the War Office and the Admiralty both had small intelligence staffs that relied on diplomats and attachés, they were models of open-source intelligence acquisition and did not want to change. When it came to espionage or any secret intelligence collection, they preferred to decline the honour.

Cumming, however, would not cease to try and be ‘useful’ until he reached a position of power. He knew that the road to power was keeping the nation’s secrets. But knowing one secret too many would ultimately cost his life, at the age of only 64.

Accepting this reality and recognizing the increasing public ‘spy fever’, the Committee of Imperial Defence established a subcommittee to create an organization ‘that could handle such delicate matters and ensure government officials did not have to dirty their hands by dealing with spies’.

Hence, in 1909, the independent Secret Service Bureau (SSB) was established with two branches, briefly housed together. The Domestic Branch initially subordinated to the War Office, and later to the Home Office, eventually became MI5 and was publicly avowed though not publicized. The Foreign Branch was placed under the Admiralty but, for cover purposes, was designated MI1c, later MI6, and headed by Captain Smith-Cumming.

There is no doubt that Smith-Cumming misappropriated money from the department. There were constant battles with the government over the allocation of running expenses. Churchill would have known this, especially during his term as First Sea Lord of the Admiralty. He knew that Smith-Cumming was ‘probably stealing’ but chose to ignore it as he had become one of the ‘inner circle’ and, as such, Churchill turned a blind eye.

By 1923 Smith-Cumming was ready to retire. Notwithstanding a modest salary, he owned no less than four aeroplanes, eight yachts, and certainly led the lifestyle of a wealthy man.

Coincidentally, he was appointed CB in 1914 and KCMG in 1919, all sponsored by Winston Churchill, but then by 1919, Churchill had a strong desire for his mother’s demise and had become more than friendly with Smith-Cumming, to the extent that Smith-Cumming was indeed the keeper of the Churchill secret.

To Churchill’s credit, he did not over-react to the information that Smith-Cumming relayed about Lady Randolph, but he was hurt and afraid. Smith-Cumming had become powerful, and Churchill understood well that his secret was at the overriding discretion of the head of MI6. The fact Churchill knew, or suspected, or could prove Smith-Cumming a thief, was by no means to be compared to Smith-Cumming knowing Churchill was a blackmailer and murderer.

Churchill simply, now, had to bide his time. He was no stranger to violence and use of force as a government minister. He was instrumental in having paramilitary forces (Black and Tans & Auxiliaries) intervene in the Anglo-Irish War. Churchill was a staunch advocate of foreign intervention, declaring that Bolshevism must be “strangled in its cradle”. He fully advocated the use of tear gas on Kurdish tribesmen in Iraq and even considered the use of poison gas in putting down Kurdish rebellion, but it was not used, as conventional bombing was considered effective.

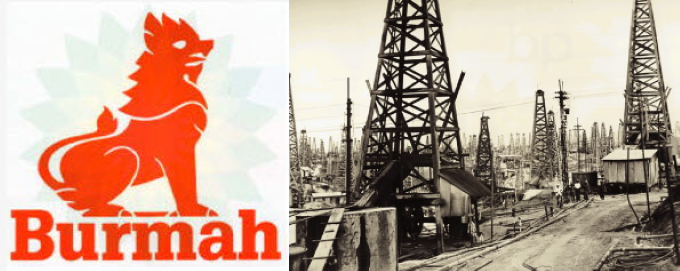

But, in 1923 Churchill was as always in need of money and acted as a paid consultant for Burmah Oil (now BP) and lobbied the British government to allow Burmah Oil to have exclusive rights to Persian (Iran today) Oil resources, which were successfully granted. For this concession and lobbying, Churchill was paid £5,000 by Burmah Oil, equal today to over £1,000,000.

When, by 1923, Smith-Cumming needed money, who better to approach than his chum Churchill, whom he knew had been paid by Burmah Oil. Although Smith-Cumming had married a wealthy woman with a substantial marriage settlement, he spent faster than he earned. He could not misappropriate much because of late the government had closed the spy stations in Madrid, Lisbon, Zurich, and Luxembourg. Smith-Cumming was particularly fond of Switzerland where it was subsequently discovered; he held a number of accounts.

Churchill met Smith-Cumming on a number of occasions, each time with a request for money. At some stage Smith-Cumming made clear to Churchill that if he was not ‘assisted’, then the information Smith-Cumming held on Churchill would be made public.

It was then that Churchill knew his friend and head of the Secret Service simply had to die.

Sir Bernard Spilsbury, on the other hand, was going from strength to strength, ably assisted by Winston Churchill. By early 1923 he was knighted. Having ensured the conviction and execution of Dr Hawley Crippen in 1922, he turned his attention to a subject that would fascinate Spilsbury to his death. That subject matter was helpful to Winston Churchill in committing his second murder.

The trial of Major Armstrong for the murder of his wife began at Hereford, before Mr Justice Darling, on 3 April 1922. Public and media interest was enormous. A year earlier there had been a trial near Hay of another solicitor, Harold Greenwood for the murder of his wife by poison, supposedly disguised as an illness. Greenwood had been acquitted. Also, the fact that the three men who brought the charges to the police included Armstrong’s business rival and the latter’s father-in-law looked suspicious to some people. It was believed by some that Armstrong was being framed, but despite the widespread belief that he would be acquitted; the prosecution case was a strong one.

Katherine Armstrong’s body was riddled with arsenic and at the time of her death the ingested quantity must have been far higher, and Armstrong had made a huge purchase of arsenic. The defence had somehow to make the jury believe that Mrs Armstrong had committed suicide by getting out of bed, going downstairs and helping herself to arsenic without anyone seeing or hearing her; or that massive doses of arsenic had somehow got into her system some accidental way. All witnesses confirmed that towards the end she was almost paralysed.

Dr Bernard Spilsbury insisted that the fatal dose must have been taken within twenty-four hours of death, and the family GP Dr Hincks affirmed that for Mrs Armstrong to have taken it herself was ‘absolutely impossible.’

The evidence against Armstrong, though considerable, was nonetheless purely circumstantial. No one had actually seen the Major administering poison, and at the time of his arrest, he had made no attempt to draw upon his dead wife’s fortune. Mrs Armstrong had occasionally spoken of suicide, some medicines contained arsenic, and there were plenty of other people coming into contact with her at Mayfield. The prosecution failed to show how it was Armstrong and only Armstrong who administered poison, and no one else. Armstrong made no confession, and adamantly maintained his total innocence until the bitter end.

On 13th April 1922, at Hereford Shire Hall, Armstrong was found guilty of the murder of his wife. Mr Justice Darling stated that he concurred with the jury’s view and that it was absurd and unsupported by any evidence that Mrs Armstrong had committed suicide. He then sentenced Major Armstrong to death commending the evidence of Dr Bernard Spilsbury. He was hanged at Gloucester Prison on 31 May 1922.

The News of the World reported that, when asked by the prison governor on the morning of the execution if he had anything to say, the Major’s last words were ‘I am innocent of the crime for which I have been condemned to die’.

The case was important for Spilsbury because he had also confided to Churchill that the evidence, he had given at the trial may have been misinterpreted. It was, after all, an opinion on a factual event, not a scientific or medical finding.

He met Churchill on numerous occasions in 1922 and 1923 but, more importantly, Spilsbury was by now an expert on poisons, and Churchill needed his expertise.

Spilsbury corresponded with many doctors worldwide. One such was Arthur Lawen of Leipzig who was researching the use of a poison called Curare, for anaesthesia. Having been made aware of the problem by Churchill, it was Spilsbury who suggested that a small dose of curare in its highest form would certainly resolve this problem.

On Thursday, 14th June 1923, Churchill asked to see Smith-Cumming, but not in the MI6 offices. He told Smith-Cumming he had the money for him, the very same money that Smith-Cumming had requested that would defray his creditors.

Although Smith-Cumming was indeed a workaholic and kept a daily diary, often arriving at his office early in the morning and leaving late at night seven days per week, on this Thursday he decided to go home early as he had an ‘important person’ to see.

Before Smith Cumming left the spy headquarters to go home to Kensington, he received a message that a man would deliver an envelope to his house in Kensington. It mattered not to Smith-Cumming who delivered the money, so long as he received such.

Smith-Cumming received a caller to his house that day, and suddenly he collapsed dead. A simple pinprick does the trick. Curare leads to asphyxiation owing to the inability of the victim’s respiratory muscles to contract. Death is almost instantaneous and almost undetected.

By 1923, Smith-Cumming was not at all well-liked and was suspected as misappropriating money from the Secret Service. No one could quite understand his source of income, but no one dared to question or investigate him.

Spilsbury supplied the Curare, and an ‘Irish male’ recruited by Churchill supplied the lethal dose, having been paid £500 to disappear to America.

Churchill had committed his second murder – again undetected.

It would be 12 years before Churchill would rid himself of yet another in whom he had confided. Lawrence of Arabia would ultimately pay the price for being a Churchill confidante.

Thomas Edward Lawrence was the illegitimate son of Sir Thomas Chapman, an Anglo-Irish baronet, was born in Tremadog, Wales on 16th August 1888. Educated at Oxford High School, he developed a strong interest in archaeology and military history. An intelligent boy he won a history scholarship at Oxford.

In 1911 Lawrence was recruited by D. G. Hogarth of Ashmolem Museum to join an archaeological expedition, led by Sir Flinders Petrie at Carchemish, on the Euphrates.

As the dig was closed down during the summer months, he used this time to explore the area. It also gave him the opportunity to learn to speak numerous Arab dialects.

On the outbreak of the First World War Lawrence was recruited by army intelligence in North Africa and worked as a junior officer in Egypt. In October 1916 he was sent to meet important Arab leaders in Jeddah. After negotiations, it was agreed to help Lawrence to lead an Arab revolt against the Turks.

Lawrence of Arabia, as he became known, carried out raids on the Damascus-Medina Railway. His men also captured the port of Aqaba in July 1917. Sympathetic to Arab nationalism he helped established local government in captured towns such as Deraa.

By December 1917, General Allenby and his army had captured Beersheba, Gaza and Jerusalem. The following year the British defeated General Von Sanders and the Turkish-German Army in Palestine. Lawrence joined Allenby’s forces and entered Damascus on 1st October 1918.

He had been converted to the cause of the Arabs, and felt they were betrayed by the treaties agreed at the Paris Peace Conference. He was particularly concerned about the decision to give the French control over Syria.

In 1921 Lawrence joined the Middle East Department of the Colonial Office. He also served as special adviser on Arab affairs to Winston Churchill, the Colonial Secretary (1921-22). Both men visited the Middle East in an attempt to deal with the growing conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine.

After leaving the Colonial Office he changed his name to John Hume Ross and enlisted into the RAF. After four months reporters from the Daily Express discovered what he had done, and he was discharged. In March 1923 he joined the Tank Corps as Private Thomas Shaw but only served until 1925.

His account of the Arab revolt, ‘The Seven Pillars of Wisdom’ was published privately in 1926. Later that year he re-joined the RAF and served for two years on the north-west frontier of India.

He continued to write, and other books by Lawrence include ‘Revolt in the Desert’, ‘The Mint’ and a new translation of ‘Homer’s Odyssey.’

In March 1935 Lawrence left the RAF.

But it was the close friendship with Churchill that would ultimately cost him his life. Lawrence was a prolific writer and he wanted to write about his experiences at the Paris Peace Conference. It was there that Churchill had confided to him how he despised his mother, loathed her morality, and told Lawrence how Lady Randolph had robbed him and his brother of their birth right.

In return, Lawrence found in Churchill a man who was able to listen and absorb the most inner of secrets. He told Churchill of the fateful days under the Turks and the obscenities he had to endure. Churchill felt at ease in 1921 for although he despised his mother and told Lawrence he would not ‘shed a tear’ if she died, she was still alive.

Lawrence had always stated he would not add to his book ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’ but desperately wanted to write in precise detail all that had occurred at the Paris Peace Conference including a chapter on Churchill.

Throughout the years he tried to put pen to paper. In one letter recovered from the Security Services archive addressed to author Robert Graves dated August 1927, Lawrence told his friend clearly ‘I want to write’. One month later to H.S. Ede the tone is much different. In a letter also recovered Lawrence wrote ‘I cannot write fluently’.

Churchill became aware of the turmoil Lawrence was going through, since 1927. All his life Churchill had been a gambler. In his first budget as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill returned Britain to its pre-1914 monetary system, whereby sterling was fixed at a price reflecting the country’s gold reserves. This was fatal and resulted in massive deflation and overvaluing of the pound. This made British manufacturing industries uncompetitive, which in turn exacerbated the massive economic problems Britain was to face in the 1930s.

But none of this was of any concern to Churchill. He never once cared for anyone other than himself ever since being cheated by his mother of what he deemed was rightfully his.

By 1931 he was out in the cold and had much time on his hands. He spoke vociferously against Mahatma Gandhi and independence from India perhaps because he had invested capital there and did not want to spoil his profits. He became estranged from the Conservative Party leadership and spent much time writing his books ‘Marlborough: His Life and Times’ about one of his ancestors and ‘A History of the English-Speaking Peoples’.

In the background T E Lawrence was writing to his friends about new books and the real story behind the Paris Peace Conference of 1921. Churchill knew this and was receiving regular news. He and Lawrence were friends and could not possibly understand why Lawrence would want to disclose confidential information.

On two occasions, one in 1934, and early 1935, Churchill met Lawrence in the Isle of Man at his cottage in Wareham, Dorset. There Lawrence reiterated his feelings to Churchill about his time in Turkish custody. He asked Churchill whether the time was nigh to write one’s most inner secrets.

Churchill was alarmed at the thought because Lawrence had connected the comments made by Churchill at the Paris Peace Conference and the death of Lady Randolph, only a few months later. Amongst papers that Lawrence left strangely was research he was carrying out on sprains and development of gangrene.

It was clear to Churchill that Lawrence by probing and researching what he thought was long forgotten, he had connected and was suspicious. That would cost Lawrence his life but, this time, without the ever-ready Dr Spilsbury.

For many years Churchill had maintained a close working relationship with the Irish Republican Army, and he saw through the Irish Free State. Churchill was not afraid of using them for his own purposes. He had used one in the murder of Smith-Cumming. He was ready to use one again.

Churchill knew that Lawrence was an adventurer and that he loved his motorcycle more than probably his typewriter. The experience Lawrence underwent at the hands of the Turks made it impossible for him to have any sensible relationship. His love was transferred to his motorcycle, his cottage and typewriter.

On Monday 13th May 1935 the much-prized motorcycle Brough Superior SS100 underwent a loosening of the brakes. Lawrence went out for a ride every day, and the route was always the same, Cottage at Cloud Hill, Wareham, Dorset, through Wareham. There were road works and, approximately one mile after, a boy who had been recruited by ‘the Irish Man’ whom Churchill had paid £1000, stepped in front of Lawrence with a bicycle.

That boy was called Albert Hargreaves and would remain in hospital, also, in ‘protective custody’ for days, prior to being discharged and suddenly leaving for the United States.

The murder of T E Lawrence was not going to be as easy as the murder of his mother and Smith-Cumming. Lawrence, unlike the other two, was much loved by the Nation and the King. Lawrence was being cared for at the Wool Military Camp Hospital, Dorset. A bulletin issued by the hospital on 18th May 1935 spoke of the ‘gravest concerns’ for Lawrence.

After a day of great and increasing tension, it was decided to seek further advice and Mr H. W. B. Cairns, the London Hospital brain specialist, was summoned.

Such was the importance and concerns for Lawrence that he motored from his home at Arundel, 100 miles away, and arrived at 12.20 in the morning. Forty minutes later, Sir Farquhar Buzzard, the King’s physician, joined the other doctors at the bedside having travelled by car from Oxford. He was the authority on nerves and was one of the specialists called in during the King’s illness in 1928.

Lawrence was admitted under the name of ‘Shaw’ and, after five days of unconsciousness, the bulletin took ‘a sudden change and the position is now very grave.’

Congestion of one of the lungs set in and it seemed Churchill’s plan had gone well. On Saturday, 18th May 1935, at 6.45, Captain C. P. Allen, the Specialist who had been attending ‘Mr Shaw’ throughout the week, issued the bulletin quoted above, announcing a change for the worse in the ‘patient’s condition.’

When it was realised that the crisis had been reached, Sir E. Farquhar Buzzard, physician-in-ordinary to the King, Mr H.W.B. Cairns, the brain specialist of the London Hospital, and Dr Hope Gosse, the London lung specialist, was called to the hospital.

At 11 o’clock that evening oxygen was administered to ‘Mr Shaw’, whose condition then was very critical.

The next day, Sunday, Lawrence died. He was 46 years of age.

Churchill, being a friend, spoke about a post-mortem to his friends, saying how it was possible that a simple motorcycle accident could take the life of his friend.

By 1935 Churchill was becoming more popular, especially warning of the dangers of Germany being re-armed. He had a voice, and Lawrence was his friend.

There had been talk that Lawrence had been murdered by foreign agents. Another story emerged that the secret service faked his death so as to allow him to undertake, incognito, important work in the Middle East.

Such was the gossip mostly inspired by Churchill to detract from the real facts that the brother of Lawrence made a statement to the press. Mr A. W. Lawrence, after he had visited the hospital on Saturday afternoon, ‘expressed a wish to deny various rumours’ which, he said, had been circulated regarding his brother and secret service.

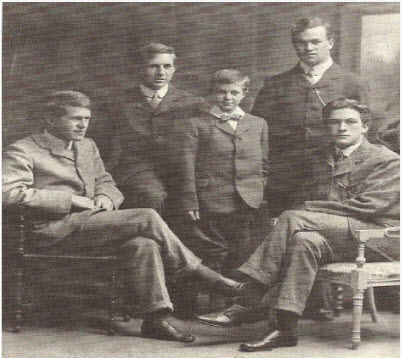

The Lawrence brothers in 1910 – Thomas (left), Frank, Arnold (centre), Bob and Will

‘One thing I wish to deny very emphatically’, he said, ‘is the story that my brother recently went to Berlin. That story, like others which are going the rounds, is absolutely untrue.’

Whilst that seemed the end of it for Churchill, he had to be sure Lawrence was indeed dead and that he had not been double-crossed by his friends from Ireland and the British Secret Service. The only way to ensure death was postmortem.

It was carried out by Mr H.W.B. Cairns, the London specialist, and after the following statement was issued: –

‘The post-mortem examination conducted by Mr Cairns showed such severe lacerations and damage to the brain that in the event of his recovery he would have only regained partial use of his speech and eyesight. In view of the immense activity and energy of Mr Shaw, it is felt that this may be some consolation to those who had entertained anxious hopes of his recovery.’

The brain was damaged because a second boy hiding in the bushes had repeatedly smashed the head of Lawrence on the ground. The motorcycle accident injured him, but the injury was not fatal.

Churchill’s £1000 was wisely and efficaciously spent. At the forefront of the funeral precession were Winston Churchill and his wife.

What Churchill, however, was not able to find – notwithstanding that Clouds Hill in Wareham, the cottage so loved by Lawrence, was searched thoroughly – was the manuscript that Lawrence had written, including the chapter about the Paris Peace Conference.

Lawrence wrote his book three times because he had on previous occasions lost the manuscripts, once whilst changing trains at Reading railway station. Lawrence had accurately recalled and recounted the confessions of Winston Churchill in Cairo 1921 but Churchill, irrespective of offering money throughout the years to come on the pretext of acquiring works of his friend, never found the manuscript.

It exists, though, and carries the proof that correlates the three murders. The first murder Winston Churchill carried out solely for the injustice he felt his mother had caused by stealing money from his father’s will. The second murder was because he was blackmailed by his confidante and felt betrayed. The murder of Lawrence was for the fear he would be exposed for what he was: a murderer.

Churchill was deep down a coward, liar, and caused the unnecessary deaths of over 250,000 soldiers, probably more. That he murdered three people for the reasons stated is of no surprise.

In 1916, Churchill used his many contacts in high places to wangle his way out of the trenches, during his brief time on active service with the Royal Scottish Fusiliers, to a safe civilian billet in London. Private soldiers were being put before the firing squad for enacting their own personal interpretation of this ambition. Once back in Britain, he remained true to his caddish self.

Concerned about the threat to his family of the Zeppelin attacks on London, he bought a country house at Lullenden, in Surrey, where the Germans couldn’t get at him.

It was around this time that he uttered these imperishable words to the House of Commons: ‘My only purpose is to help defeat the Hun, and I will subordinate my own feelings so that I may render some assistance.’

This was from the man who had just fled the trenches.

This man also was known to quote ‘The Dark Dog’ referring to the three murders, but only he knew the true meaning of the quote.

Shortly afterwards, he boasted laughingly to friends that he often used precious petrol — issued to him for ministerial purposes only — for social trips. He soon moved political heaven and earth (successfully) to prevent his parkland at Lullenden from being ploughed up to produce food, even as the U-boat threat came close to throttling Britain.

As Lloyd George — no slouch himself in the ego-department — acidly commented: ‘You will one day discover that the state of mind revealed in (your) letter is the reason why you do not win trust even where you command admiration. In every line of it, national interests are completely overshadowed by your personal concern.’

Prime Minister Lloyd George was right.

GDS

Soon to be a docu/drama – more to follow

NB: Some images retrieved from Google, will remove at owner’s request.