“Jeremy Bamber a truly innocent man has now been imprisoned for almost four decades.”

“Having passed a lie detector test with detailed questions, and despite the passage of almost 20 years the Ministry of Justice has miserably failed to investigate properly. My publishing this article in June 2013 had a prejudicial effect on how myself has been treated. I was due to be returned to Italy in 2014 and mysteriously the British Government violated international law and refused to send me.

In the middle of my trial an MI6 officer went to see my trial Judge with a letter to date not properly explained. Between 2017 and 2019 a number of High Court Judges met to discuss my case, and to make sure that any application I made would fail. This is about credibility.

Jeremy Bamber is but one of my clients who are totally innocent of the crimes convicted. I stand by every word that I published and will continue my own fight against what is now clearly a rogue State that has no respect for international law, national law and instead of calling internationals citizens it refers to them as subjects.

I call upon all those who truly advocate for democracy to make their voices heard to their MPS and vote accordingly when the time comes.”

Giovanni Di Stefano

Was Mi6 Involved In A Series Of Murders That Lead To Jeremy Bamber Jailed For Life

Sixty years ago, a Hillman saloon pulled off the N96 near the village of Lurs, about 75 miles from Aix. It was a stifling Provençal afternoon and the car’s occupants, the distinguished British scientist Sir Jack Drummond, his wife Ann, and their 10-year-old daughter Elizabeth, decided to camp out for the night by the banks of the river Durance.

Within hours they became the centre of one of France’s most troubling criminal puzzles, variously shot and clubbed to death. The tragic demise of the Drummonds is a murder mystery that has fired the public imagination for half a century.

It was not just the victims’ renown and the consequent fuss across the Channel: Sir Jack, a 61-year-old former professor of biochemistry at London University, had been knighted for his exceptional work in nutrition during the Second World War and was a senior researcher at the Boots laboratory in Nottingham.

Nor was it the unlikely and altogether too handy perpetrator fingered by the police and convicted 18 months later: Gaston Dominici, a 75-year-old peasant farmer whose smallholding was the nearest property to the scene of the crime, was a pillar of the local community.

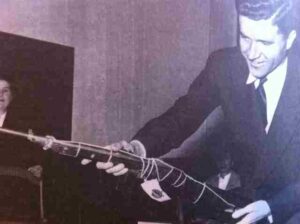

No, it was the many key questions that remained unanswered. What was Dominici’s motive? Where did the murder weapon, a battered US army Rock-Ola carbine, come from? What of the unidentified men seen on the road? And was Sir Jack, as Fleet Street soon began claiming, rather more than just an eminent scientist?

After more than a dozen books and thousands of newspaper articles on ‘L’affaire Dominici,’ startling new evidence neglected during the original investigation has been discovered. This evidence now opens some intriguing new lines of inquiry.

“I don’t think Gaston was the author of the triple murder of Lurs,” said one police officer that was on the case many years ago. “I think the family was a pawn among others, caught up unwittingly on the chess board of a secret battle fought between east and west over each bloc’s leading scientists. Jack Drummond, we are almost certain, was a spy.”

It is this belief that led Giovanni Di Stefano then lawyer for convicted murderer Jeremy Bamber into advancing the theory that Bamber was innocent of the murder of his adopted parents, his sister and two children. “They were murdered as part of a spy ring,” Di Stefano told the press.

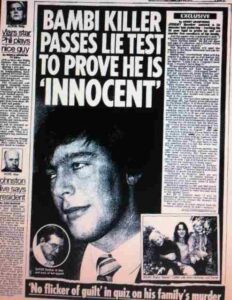

Challenged on the truthfulness of Bamber at his trial, the British Government allowed Bamber to take a detailed lie detector test in prison. Bamber passed and the British Media had a field day.

- Did you shoot your family on August 7th, 1985? – No

- Did you shoot five members of your family with an Anschutz rifle? -No

- Were you present inside the house when they were shot with an Anschutz rifle? No

- Did you shoot your father Nevill? – No

- Did you shoot your mother June? – No

- Did you shoot your sister Sheila Caffell? – No

- Did you shoot your twin nephews Daniel and Nicholas? – No

- Did you climb out of a window of your parent’s home after shooting your family? No

- Did you shoot your family in your father’s home? – No

- Did PC Bews radio in a report of seeing someone in an upstairs window around 4am on the morning of the shootings? – Yes

- Did you pay a professional hit man to shoot your family? – No

The spy ring murder proclaimed by Di Stefano in 2005 was sensational news. The story made most of the tabloid press and caused a serious problem at MI6 headquarters.

“Mass killer Jeremy Bamber is to claim that his father was killed by a mystery Mr X as he launches his third appeal.

Four of Nevill Bamber’s, intelligence services colleagues have been murdered in amazingly similar circumstances over the past 53 years.

Each served with Nevill during the Second World War – and each case is STILL unsolved.

Bamber, 44, has always denied gunning down five members of his family at their farmhouse in Tolleshunt D’Arcy, Essex, to claim a £500,000 inheritance.

The bizarre new claims have been made by a former SAS officer and could be the icing on the cake for Bamber’s appeal case.

The murders being linked are:

* Scientist Sir Jack Drummond, murdered with his wife and 10-year-old daughter on a camping holiday in France 1952. It has since been claimed that he was a spy.

* Sir Jack Drummond’s secretary Miss June Marshall, murdered in Dieppe, France, In 1956.

* Sir Oliver Duncan was murdered in Rome, in 1964.

* Major Michael Lasseter was murdered in Cannes, France, in 1973.

* Professor John Cartland, also known as a former secret agent, murdered on a camping holiday in Provence, France, in 1973.

The ex-SAS officer told Bamber’s lawyer Giovanni Di Stefano that all five men worked shoulder-to-shoulder in the British intelligence service during and after the war.

Mr. Di Stefano that night pressed the Ministry of Defence for an investigation.

However, MoD officials and the police are likely to dismiss the claims as a “conspiracy theory.”

It gives Bamber – who murdered five members of his family – new hope after he launched his third appeal with a picture exclusively revealed in The Sunday Mirror 10 months ago.

The picture – taken between 8.30am and 9am on the day of the murders in 1985 but not seen by the trial jury – shows blood pouring out of the wounds in his sister Sheila Caffell’s neck.

His legal team – backed up by two medical experts – claim that the picture shows that Bamber could not have been the killer as he was outside with police at the time of the murders.

They yesterday received a medical report which confirmed that their client could not have been the murderer.

The report states that Sheila Caffell could not have died “more than two hours from the discovery of the corpse itself”.

She was discovered at around 7.30am while Bamber was with police from around 3am.

Mr Di Stefano said the new claims about Nevill Bamber’s colleagues must be investigated.

He said: “All of these men knew each other because of the common

denominator that they all worked for British intelligence during or after

the war.

“They all died in mysterious circumstances and do not have anybody brought to justice.

“It is far too coincidental that over a period of 30 years that all of these people linked to each other were murdered mysteriously.

“I will be pressing the MoD to look into this as if there is a person or organisation that has carried out all of these murders.

“It has to be looked into whether there was a campaign of murder against former British intelligence officers – including Nevill Bamber.

“If it is the case, it clearly shows that Jeremy Bamber is innocent.

A police radio log – not shown to the jury – showed that officers were in contact with somebody in the house at 5.25am on the day of the murders

Mr. Di Stefano added: “This furthers the case that the murders were carried out by a third party and not Bamber or his sister Sheila.

“These people were all involved in the intelligence service and then systematically annihilated.

The murders of Sir Jack Drummond, his wife Lady Anne Drummond and their 10-year-old daughter Elizabeth at their campsite in northern Provence, in August 1952, was one of the great cause’s ‘celebres’ of the post- war years

Gaston Dominici, a 77-year-old peasant farmer, was convicted of shooting the parents and bludgeoning the child to death but was pardoned by President Charles de Gaulle in 1960.

A French journalist has claimed that the family were murdered by a Soviet hit squad, but those allegations were rubbished.

After John Cartland was hacked to death in 1973 his son Jeremy was accused of the crime – despite being stabbed himself – but was never charged.

Shortly after the murder anonymous phone calls to media organisations claimed that Cartland’s death was linked to a series of killings of Britons who worked in wartime intelligence.

They said that the alleged chain of murders started with the death of Sir Jack Drummond and his family followed by the murder of former counterintelligence officer Sir Oliver Duncan in Rome in 1964.

This was followed by the ‘mysterious’ death of Colonel Michael Lasseter in Cannes, France in 1973.

Another anonymous tip off claimed that the murder of Sir Jack’s secretary in Dieppe in 1956 was also linked.

Psychopath Bamber was convicted of gunning down his adoptive parents Nevill and June Bamber, sister, Sheila Caffell and her twin sons Nicholas and Daniel, who were six.

Bamber was 25 when he was locked up for the murders.

At first police believed his schizophrenic sister Sheila, a model, nicknamed Bambi with a history of mental illness, killed her family before turning the gun, a .22 semi-automatic rifle, on herself.

But they changed their minds when relatives discovered a silencer for the murder weapon, which officers had missed, with a spot of blood inside that was said to be Sheila’s.

Detectives reached the conclusion she could not have killed herself and then put the silencer back in the cupboard where it was found.

Bamber lost an appeal against his conviction in 2002.

The Criminal Cases Review Commission is reviewing the new picture evidence and whether to grant a new appeal hearing.

Examine the facts that led to Gaston Dominici’s conviction in one of the ‘soy ring murders.’ It was his son Gustave who alerted the local gendarmes, hailing a passing cyclist at 6am on August 5 to say he had found a body. Elizabeth Drummond was lying near the river, her skull stove in with a rifle butt.

Lady Drummond’s body was found near the car, and Sir Jack’s just across the road. Both had been shot from behind. The broken stock of the Rock-Ola was found floating in the Durance, and the barrel was found later on the riverbed.

At first Gustave told police that he had heard shots at about 1am and thought poachers were out. He had found Elizabeth’s body at 5.30am. Gaston confirmed the story, adding that he had seen the Drummonds the night before while he was tending his goats.

Almost similar timing to the Bamber murders.

Gradually, however, the family’s story began to reveal inconsistencies: a neighbour, Paul Maillet, told the police that Gustave had said he found Elizabeth alive. Then Gaston’s nephew came forward to say he had seen Lady Drummond and Elizabeth call at the farm with a bucket, asking for water – when the Dominici’s had sworn they had no direct contact with the Drummonds at any time.

Eventually Gustave and his elder brother Clovis broke down. They told the police that their father had admitted having “killed the English”. Old Gaston confessed in his turn, only to withdraw his statement soon afterwards, saying he had admitted the crime “to protect my family”. Gustave then also retracted.

None the less, in November 1954 Gaston was found guilty and sentenced to the guillotine. The evidence clearly did not satisfy two successive Presidents of the Republic: in 1957 René Coty commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, and in 1960 Charles de Gaulle freed him.

“Gaston had no motive,” said one lawyer observing the case. “His initial explanation that Sir Jack had caught him in a compromising situation with Lady Ann is laughable. But there is a lot more: the rifle clearly wasn’t his, and he didn’t know how to use it.”

An examination of the case in detail shows the bizarre and unrelated arrest in Germany sometime later of William Bartkowski, a sinister figure who confessed spontaneously to having been one of four contract hit men involved in the Drummond murders, which to date has never been explained. The post-mortems on Sir Jack and Lady Ann show different-sized entry wounds, indicating that two weapons had been used. And at least four local passers-by said in evidence that they saw strangers, meeting the description of neither the Drummonds nor the Dominici’s, close to the car that night.

Similar circumstances in the Bamber case where maybe more than one firearm was used.

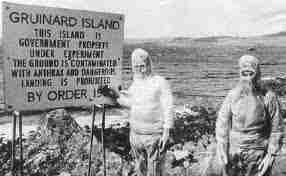

But the most interesting line appears to be Sir Jack’s real purpose in visiting the area. Drummond had been to Lurs at least three times before, in 1947, 1948, and 1951. Six miles from the village is a chemical factory that had begun producing advanced crop insecticides, widely feared during the cold war for their military potential. Was he on an espionage mission? His camera, certainly, was never found.

Between 1948 and 1952, a 25-year-old Nevill Bamber also visited the same area on at least three occasions.

Even more intriguingly, Sir Jack had a lengthy meeting with a certain Father Lorenzi in Lurs two days before his death. The priest, who died in 1959, was a celebrated Second World War resistance hero. Why would an eminent British scientist seek out a former Maquisard? And what did Father Lorenzi tell Paul Maillet, a fellow resistance fighter, and a close friend of Gustave Dominici’s he was sure Dominici to be the true owner of the Rock-Ola rifle?

The Dominici’s strange behaviour indicates they knew a lot more about the crime than they ever let on. However, they were not guilty of the murders. They plainly got caught up in something far bigger than themselves.

In February 1940, Drummond had been appointed chief scientific adviser to the Ministry of Food, where he did more than perhaps any other single individual to ensure that the island of Britain survived the Nazi U-boat blockade without starving. In fact, the health of the British nation, schoolchildren included, was not just maintained during the Second World War but improved. The American Public Health Association reported that:

In February 1940, Drummond had been appointed chief scientific adviser to the Ministry of Food, where he did more than perhaps any other single individual to ensure that the island of Britain survived the Nazi U-boat blockade without starving. In fact, the health of the British nation, schoolchildren included, was not just maintained during the Second World War but improved. The American Public Health Association reported that:

“The rates of infantile, neonatal and maternal mortality and stillbirths all reached the lowest levels in the history of the country. The incidence of anemia and dental caries declined, the rate of growth of schoolchildren improved, progress was made in the control of tuberculosis, and the general state of nutrition of the population as a whole, was up to or an improvement upon pre-war standards.”

Indeed, the incidence of almost every diet-related illness was lower than it had ever been. Drummond was a genuine home-front hero.

The turning point in his career was the publication in 1939, of his only book: ‘The Englishman’s Food A History of Five Centuries of English Diet.’ The title sounds dry, but the book is a highly readable blend of social history and biochemistry. It is even funny in places. The historical perspective illustrated quite how much and how often our eating habits had changed.

The eve-of-war timing of the publication of The Englishman’s Food was crucial, because the book demonstrated brilliantly that malnutrition was not just a social issue but also a pressing military one. Poor nutrition could directly affect the performance of troops in the field. By 1939, Britain was dependent on imports for almost two-thirds of its food supply, above all on wheat from the US and Canada. At the height of the U-boat campaign in 1940, Hitler’s submarines destroyed 2.6m tons of merchant shipping.

At the new Ministry of Food, Drummond produced a plan for the distribution of food based on “sound nutritional principles”. From the start he regarded rationing as the perfect opportunity to attack what he called “dietetic ignorance” and recognised early on that, if successful, he would be able not just to maintain but to improve the nation’s health.

A plain but balanced diet, Drummond had discovered, was the nearest thing to the elixir of life.

The weekly ration

Bacon and ham: 4oz

Other meat: to the value of 1s 2d

Butter: 2oz

Cheese: 2oz

Margarine: 4oz

Cooking fat: 4oz

Milk: 3 pints + 1 packet dried skimmed milk per month

Sugar: 8oz

Preserves: 1lb every 2 months

Tea: 2oz

Eggs: 1 shell egg +1 packet dried egg per month

Sweets: 12oz

Meanwhile the Ministry of Agriculture was intent on persuading Britons to plant their own food. Under the patriotic banner slogan “Dig for Victory”, self-sufficiency became the new Holy Grail. It was considered the duty of all householders to turn their back gardens into vegetable patches. Windsor Great Park was given over to wheat. Even Lord’s Cricket Ground was not spared. Between 1939 and 1944, the arable land area in England and Wales increased by 63%. Wheat, barley, and potato crops almost doubled, while the production of oats rose by two-thirds, and Drummond provided the science behind the spadework.

Because shipping space was at a premium, food imports also had to be drastically reorganised. At Drummond’s instigation, priority was given to cheese, skimmed dried milk, tinned fish and meat, and pulses. The technical ability to preserve food in cans had been mastered in the mid-19th century, but it was not until the 1940s that the process really took off. The advantage from Drummond’s point of view was that canned food retained its vitamins.

He paid special attention to society’s “vulnerable groups”, as they were designated for the first time. Children and expectant or nursing mothers headed the list, receiving rations of blackcurrant and rosehip syrup as an alternative source of vitamin C, before concentrated orange juice became available.

Today, vitamins are the centrepiece of the modern food industry’s most controversial growth area: the sector known as nutraceuticals, or techno foods. Processed food staples such as margarine, cereals and orange juice are fortified with vitamins and other “scientific” ingredients associated with good health and marketed to a credulous public. Pepsi Co, for example, which owns the juice brand Tropicana, sells an orange-juice product called Multivitamins; it costs five times more than ordinary orange juice. Unilever’s Flora pro-active margarine, meanwhile, contains hydrogenated sterols, a plant compound that is supposed to lower cholesterol in the blood; it costs 11 times as much as regular margarine.

Those figures would have surprised Drummond. He always argued that the best source of vitamins was natural food, and that so long as an individual’s diet was plentiful and well balanced, supplements or additives were unnecessary. Thanks largely to his efforts, by 1945 an entire generation of housewives knew the rudiments of how to prepare a meal at home. They also knew a lot about vitamins – what they were, why they were important, and which foods contained them. The tragedy is how much of that hard-won knowledge has been forgotten. It is both absurd and tragic that Tony Blair’s government is trying to educate the public all over again with its proposed “traffic-light” labels on food packaging, a scheme intended to warn consumers about high levels of salt, sugar, and fat.

One of the most troubling consequences of the agrochemical revolution was the nutritive difference between the intensively grown fruit and vegetables of today and their equivalents 60 years ago. According to the government’s own data, between 1940 and 1991 the typical British potato “lost” 47% of its copper and 45% of its iron. Carrots lost 75% of their magnesium, and broccoli 75% of its calcium. The pattern was repeated for vitamins. A study in Canada showed that between 1951 and 1999, potatoes lost all of their vitamin A and 57% of their vitamin C, while today’s consumers would have to eat as many as eight oranges to obtain the same amount of vitamin A their grandparents did from a single fruit.

Organic food still accounts for only 1.2% of the total British retail food market. In 2004, Britons spent £1.2bn a year on organic produce: about three-quarters of what we spent on bottled water. Despite all the warnings and an explosion of food scares, the vast majority of people carry on as before.

Some scientists blamed chemical changes in the west’s diet for a dramatic increase in a range of maladies such as chronic fatigue syndrome, hormone-related imbalances, mental illness, even asthma and eczema in children. Some also blamed chemicals for the extraordinary decline in western male fertility in the last 20 years. In Denmark, a country particularly badly affected, 40% of men now have subnormal sperm counts.

In the 1940s the average westerner contained no man-made chemicals for the simple reason that those chemicals did not yet exist. In a recent survey conducted by the environmental organisation WWF, volunteers in 13 British cities had their blood tested for the presence of 77 man-made chemicals, including organ chlorine pesticides. Every one of the volunteers was found to be multiply contaminated.

The individual amounts of the chemicals the WWF tested for were mostly tiny and, by themselves, probably harmless. The snag, as Drummond himself pointed out more than half a century ago, was that no one was able to say what might happen to those chemicals once they accumulated and combined over time with others in the body – the “cocktail effect”.

The new industrial era in agriculture began after the war. A National Agricultural Advisory Service was inaugurated in 1946. Some 1,400 technical officers were employed to roam the countryside, offering farmers free advice on how to translate the latest scientific advances into useful reality. Overall and certainly compared with the 1930s, there had never been a better time to be in farming. It was not until 1950 that Attlee’s administration began to have misgivings about the agrochemical revolution it had done so much to encourage. A Ministry of Agriculture committee was convened in that year to examine whether the chemicals the public was increasingly exposed to might be bad for their health.

The evidence heard by the committee was conflicting and inconclusive. The human health effects even of DDT were still unknown. The final result was a terrible cop-out. The committee’s main recommendation was the setting up of another committee whose task would be to “advise generally” on problems relating to consumer health. That committee – chaired by Sir Solly Zuckerman, a zoologist by training – in the end decided a voluntary arrangement with the industries concerned was a better option than statutory controls. With that decision, ultimate responsibility for assessing the human health risk of agrochemicals was left up to the manufacturers for the next 30 years. The voice of reason represented by the likes of Drummond might not have prevailed, even without his untimely murder in 1952. Much of the chemical experimentation of the period was sponsored by the military.

In the 1950s it would have been hard even for a willing government to regulate an industry that sometimes worked for agriculture, sometimes for the military, or (in the case of ICI) for both at once.

The food expert Professor Michael Crawford of London Metropolitan University headed the university’s Institute of Brain Chemistry and Human Nutrition for the past 15 years. He was asked about chicken – in particular battery-reared chicken versus organic birds. He argued that modern food in general was not nearly as healthy as the public thought it was, a state of affairs he blamed squarely on the food manufacturers.

“Have you heard of a book called The Englishman’s Food?” he said. “It’s all in there … there’s no better account of how the manufacturers have manipulated people’s eating habits over the years in the name of profit.” And he added: “Imagine how different things might have been had Drummond lived.”

“Have you heard of a book called The Englishman’s Food?” he said. “It’s all in there … there’s no better account of how the manufacturers have manipulated people’s eating habits over the years in the name of profit.” And he added: “Imagine how different things might have been had Drummond lived.”

“There’s a suggestion in France that he was assassinated.”

“Really? I don’t know about that. But the timing of his death was certainly very … shall we say, convenient for the food manufacturers.”

“Are you saying that he was bumped off by big-business interests?”

The professor considered this, leaning back in his chair, and scratching his throat. “You need to understand the context,” he said. “The study of human nutrition was still getting off the ground in the 1950s. The establishment didn’t like it – so it was suppressed.” The nutrition movement in Britain was stillborn,” he said. To this day there is no dedicated faculty of human nutrition at any of Britain’s major universities. Crawford had himself encountered the old prejudices. He had moved to London Metropolitan University when his original berth at UCL was lost to a funding cut.

So was Drummond’s murder part of a dastardly campaign of corporate suppression, without which the course of nutritional history in Britain might have been entirely different?

According to the orthodox version of the killings, the reason for the Drummonds’ presence in France in the first place was nothing more interesting than a relaxing family holiday. Drummond was an ardent Francophile who had visited the country many times before. His daughter’s school had broken up for the summer holidays, so when Professor Guy Marrian, a biochemist colleague from his UCL days and one of his best friends, invited the Drummonds to stay at a rented villa at Villefranche-sur-Mer, near Nice, he readily accepted.

They set out from their home near Nottingham, in an olive-green Hillman estate on 25 July. They caught a ferry from Dover to Dunkerque on 27 July, and drove slowly down the eastern side of France, stopping off along the way. They spent the night in Digne in the foothills of the Alps on Friday August 1, 60 miles short of their final destination. Here Elizabeth spotted a poster advertising a charlottade, a type of bull-run, which was to take place there in three days’ time. The family was expected ‘Chez Marrian’ the following day; Elizabeth made her doting father promise they would return to see the bull-run on Monday – which they did. The charlottade took place in the late afternoon. Several spectators later recalled seeing the family in the crowd. Afterwards they had an early supper at a local hotel, L’Ermitage.

They did not take the direct route back south to Villefranche, but instead headed west along the Durance valley in the direction of Marseilles. As darkness fell (or so the newsmen again speculated), they decided to stop and camp at the roadside, at La Grand’Terre, not far from the village of Lurs.

Much of what happened next is still hotly disputed. There were no witnesses other than the Dominici’s, the peasant farmers living nearby, and their evidence was a tangled mass of contradictions, half-truths and downright lies.

At 1.10am, seven shots resounded across the valley. Gaston Dominici told the police he thought it was poachers shooting rabbits. It was not until dawn that the three dead bodies were discovered. The police investigation, led by Commissaire Edmond Sébeille of Marseilles, was a disaster from the start but it wasn’t long before he had pieced together a version of what had happened.

The motive for the murders was probably not robbery. The interior of the Hillman was an indescribable mess, yet nothing obvious seemed to have been taken, notably a 5,000 franc banknote. The murder weapon was quickly recovered from a pool in the river where it had been tossed by the killer: a battered Rock-Ola US army carbine held together with wire. The Rock-Ola was a kind of firearm that abounded in the region, abandoned or traded for food by US infantrymen as their liberation of Europe rolled northwards in the summer of 1944. It seemed probable that the gun belonged to one or other of the Dominici family.

Travelling with his team of investigators from house to house, Sébeille was met with what he described as “a wall of silence”. The investigation was eventually to drag on for 15 months, a delay for which the Commissaire was attacked by the press on both sides of the Channel.

Speculation soon began to fill the void. Big-business interests were involved. In an internal report of August 1952, a divisional superintendent called Harzig told his superiors that he believed the murders to be “an episode in the secret struggle between pharmaceutical corporations” – a suspicion prompted by Drummond’s position at the time as a director of Boots. More popular at the time was the idea that Drummond was some kind of British government spy, and the murders a murky episode of the cold war.

The testimony of a traffic policeman named Emile Marquet threw fuel on the fire. Marquet was on duty in Digne on the evening of the murders. At about 8.15pm he observed a car with British number plates pull up outside L’Ermitage, the hotel where the Drummonds had been dining an hour before. The driver – “1.80m, svelte, about 30, in T-shirt and white trousers” – asked Marquet if he had seen another English car passing that way. When Marquet affirmed that he had, the driver asked what direction it had taken. Then he went inside, leaving his companion, a “woman in black”, standing by the car. A quarter of an hour later – the time taken, say, to place an international phone call – he emerged from the hotel at a run, jumped into the car with the woman in black, and sped off in the direction taken by the Drummonds an hour before. It looked as though the Drummonds were being followed. The couple were never identified or traced.

Under mounting pressure from the police, Gustave, one of the Dominici sons, at last appeared to crack – and blurted that it was not he but his father Gaston who was the killer. He was later to retract this startling confession, only to repeat it again. In any case, the old man was arrested and eventually convicted. Had Drummond’s murder had no connection at all with agrochemicals?

His directorship at the Boots Pure Drug Company in Nottingham was the sticking point. The presumption was that the job was a cozy sinecure, a part-time position accepted in lieu of something worthy of his talents. That was not to be the case.

The mistake was to think of Boots as the kind of firm that it is today: a humdrum chain of high-street dispensaries where the nation buys its soap and toothbrushes. The company’s 19th-century origins were in retailing, it was true, but in Drummond’s time its whole direction and purpose were radically different. Here was the crunch: in the late 1940s, Boots was at the forefront of the race to develop agrochemicals, with a research department that in some respects rivaled ICI’s. Research into new agricultural, horticultural and veterinary products was a pet interest of the chairman, Lord Trent, who had taken over from his father; the company founder Jesse Boot, in 1931.

The company’s agricultural division was also greatly enlarged after the war. By 1952, when Drummond died, Boots was farming some 4,500 acres in England and Scotland purely for experimental purposes. That was not all. The directorship taken up by Drummond was the very much hands-on position of director of research; and he seemed to have thrown himself into his new job with the dedication for which he was famous.

New agrochemical products placed on the market as a direct result of the research department’s work, the chairman proudly announced at the time, included Cornox, a “selective weed killer”, and Turk-e-san, a drug for treating blackhead, a fatal liver disease in turkeys.

Turk-e-san was taken off the market many years ago. Cornox was based on a Boots-developed formula called 2, 4-DP, or dichlorprop: one of the chlorine-based phenoxy family of hormone weed killers that were chemically descended from ICI’s wartime invention, MCPA. The formula, which became a world bestseller for Boots, is still listed by the Pesticides Action Network as a “bad actor” chemical. Its long-term human health effects are uncertain but are thought to include peripheral damage to the human nervous system and possibly cancer.

That Drummond might have been responsible for the development of Cornox was confounding news. This was the man who advocated the exhaustive testing of new agrochemicals in a prestigious public lecture shortly before his death. It followed, furthermore, that Drummond could not possibly have been assassinated by big-business interests, because by 1952 he represented those interests.

Peter Campbell, the octogenarian Emeritus Professor of Biochemistry at UCL, where Drummond had worked before the war had not forgotten Drummond, whose move to Nottingham he described as “very curious”. “Drummond cut himself off entirely. His choice of Boots was curious, too. Boots never did any decent research.”

Drummond did not bother to keep a foot planted in his old camp. In 1946 he resigned his chair of Biochemistry, which he had held in absentia throughout the war, and turned his back on academia forever. “What if there was some other reason entirely for his going to Boots?”

Could Drummond have been a spy? A family camping holiday would make a classic cover. What if he really was on some kind of government mission in 1952, and then randomly murdered? The two things could be entirely unconnected.

There was much to suggest that the Drummond family’s presence at La Grand’Terre on that hot August night was no coincidence. One troubling detail was the position of the Drummond car. Police photographs and sketches of the crime scene showed that the family parked parallel to and about one foot away from the N96, a busy trunk road even at night in those pre-motorway days. It was a curiously bad choice for a family of tourists looking for a peaceful night’s sleep under the stars. The Drummonds had ample opportunity to select a better spot. There was plenty of space a little further from the road in the shelter of trees and undergrowth.

There was much to suggest that the Drummond family’s presence at La Grand’Terre on that hot August night was no coincidence. One troubling detail was the position of the Drummond car. Police photographs and sketches of the crime scene showed that the family parked parallel to and about one foot away from the N96, a busy trunk road even at night in those pre-motorway days. It was a curiously bad choice for a family of tourists looking for a peaceful night’s sleep under the stars. The Drummonds had ample opportunity to select a better spot. There was plenty of space a little further from the road in the shelter of trees and undergrowth.

If, on the other hand, Drummond had parked with the intention of being seen from the road, the location was perfect. The car was parked exactly opposite one of the tombstone-shaped milestones that punctuate the borders of all route’s nationals. This one, number 32, told drivers that they were at the exact midpoint between the two nearest small towns on the N96: Peyruis, 6km to the north, and La Brillanne, 6km to the south. Was this pure coincidence perhaps? But if Drummond had pre-arranged a meeting here, the milestone would certainly have been a useful location-finder for the other party.

There were other indications that Drummond had a secret side. It was well known he had undertaken at least two “special operations” during the war, the best known of which was his visit to the Nazi-occupied Netherlands in May 1945. In 1939, moreover, in another episode much glossed over in his obituaries, Drummond worked briefly at Porton Down, the government’s secret biological-weapons research station in Wiltshire, infamous today for its past practice of experimenting on humans. Here he conducted experiments into the fitness for human consumption of food exposed to poison gas. The work did not make him a spy, but it did reinforce the impression that his association with the secret side of government was an established one.

So had Nevill Bamber and the others all been mysteriously murdered.

Drummond, the man, also seemed to match the profile of a spy to a degree. His provenance remains mysterious: no birth certificate for him exists in the Family Records Office. The public persona he finally settled on was the “people’s scientist”. He became the one and only “Sir Jack”. He was loved and trusted by all who came into contact with him. Many people, including his close associate Magnus Pyke, noted his steady and uncomplicated sense of patriotism. Yet he amazed his colleagues by swapping academia for the world of commerce and industry in 1946.

He was a paradox.

So was Nevill Bamber.

The whodunit aspect of the murders had always engaged the French the most, but now the question of who pulled the trigger, or triggers, becomes entirely separate from the more interesting issue of what Drummond was doing at La Grand’Terre. One explanation was that he had an appointment with someone who had promised to pass on industrial secrets (with its inevitable corollary: that his contact double-crossed him and killed him instead). This theory was based on the presence of a chemical plant at Chateau-Arnoux-Saint-Auban, 12km up the river Durance from La Grand’Terre, and, also, on the assertion that Drummond’s brief work at Porton Down in 1939 had continued during and after the war. The plant wasn’t just any chemical factory, but an ex-military one that specialised in the production of chlorine: the feedstock for much of the pharmaceutical and agrochemical output of Boots.

The factory, still producing chlorine today, was converted to civilian use after 1918, but that did not make it less strategically important in 1952, when the cold war was running at full tilt and the potential applications of chlorine technology, military or civilian, were not yet fully explored.

The giant agrochemical concern Rhône-Poulenc had once controlled the chlorine plant at Château-Arnoux. Between 1947 and 1955, Rhône-Poulenc manufactured, among others, the American-invented, chlorine-based herbicides 2, 4-D and 2, 4, 5-T, the eventual constituents of Agent Orange. All these products were at the cutting edge of agrochemical development, and as such were bound to attract the interest of Whitehall’s defence specialists. Some of Rhône-Poulenc’s products, interestingly, were also closely chemically related to the chlorinated herbicides that Boots was developing at the time under Drummond’s direction, including MCPP – which was first marketed by Boots in 1953, and so probably in the final stages of development in the year that Drummond was murdered.

Was intelligence-gathering the reason for Drummond’s presence in the Basses-Alpes in 1952? Boots would doubtless have been interested in the goings-on at the chlorine plant, could it be that Drummond – altruistic, patriotic, a distinguished senior scientist – would involve himself in something as tawdry as a bid for commercial advantage.

If he truly was gathering intelligence, it seemed likelier he would have been doing so on behalf of his country.

In other words, he was working for MI6.

That was the probable explanation for Drummond’s appointment to the board of Boots in 1946. MI6 has a long tradition of “placing” its operatives within British industry. Whatever his rendezvous had been for, it was evidently important enough for him to wait up half the night at the side of a road. If he was operating under cover of a family holiday, he either tragically underestimated the danger of the meeting he had planned, or else he and his family were the unlucky victims of violence unconnected with his work.

The Bamber murders were equally as brutal as the murders of the Drummond family which also included a child. All of those murdered had one thing in common: they all knew each other and had all worked for the intelligence services in one capacity or another.

All had connections with Porton Down and all had been given respectable and important jobs enabling them to integrate within the community.

In all of the murders only one man still pays the price: Jeremy Bamber. But with the British Government relying on polygraph tests to control the activities of those released from prison and for insurance, housing, social security benefits, how much longer can Bamber be kept in prison who has passed his lie detector test?

If the Government rely on lie detector tests to control the honesty and offending of those released from jail and have included such in their Criminal Justice Act, then surely the time has come to consider the relevance of the polygraph for those who maintain their innocence?

The fact the series of murders have yet to receive a proper explanation or enquiry from the British Government makes the suspicion that Bamber has been used as a distraction more credible.

Giovanni Di Stefano

©Giovanni Di Stefano January 2013 – All Rights Reserved

NB: Some images retrieved from Google, will remove at owner’s request.

Get your facts.

June (Janet) Marshall wasn’t a secretary, she was a teacher. He never knew Jack Drummond and she was killed in France, true… by a local multi-reincident sexual predator,and for for sexual motive. The murder –Robert Avril– confessed and was convicted and sentenced. JackDrummond had a secretery, yes –Olive Antill–, but it was not this girl, and lived on years and years.

After noticing that bit of misinformation, I suspended reading about your narrative of the Bamber case. I don’t like reading from souirrces that have shown to be unreliable.