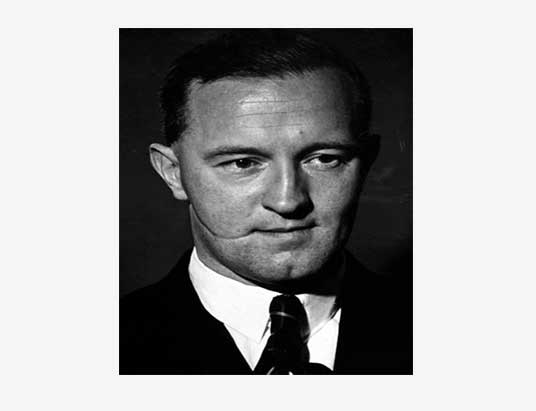

William Joyce, the man with the famous nickname ‘Lord Haw Haw,’ was Britain’s most well-known traitor of relatively recent times. He had a catchphrase as famous as any comedian’s and to cap it all he had a facial disfigurement in the form of a terrible scar that marked him as a villainous traitor, as if the words themselves were tattooed across his forehead. Saying all that, a lot of people have argued that he shouldn’t have been convicted of treason at all, let alone be executed for the crime.

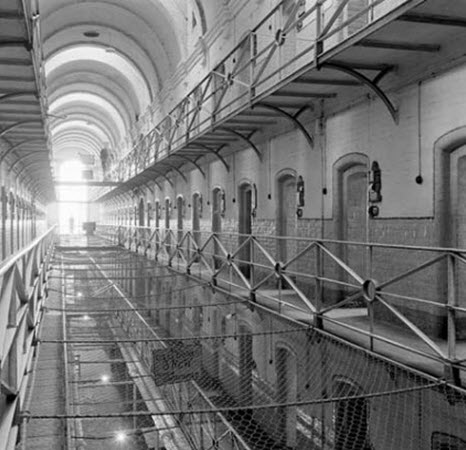

On the cold and damp morning of 3 January 1946, a large but orderly crowd had formed outside the grim Victorian prison in Wandsworth. The main gates of London’s largest gaol are situated not more than a few hundred feet from the far more salubrious surroundings of Wandsworth Common in South West London.

Some people had come to protest at what they considered an unjust conviction, while others, ghoulishly and morbidly, wanted to be as close as they could, to what would turn out to be, the execution of the last person to be convicted of treason in this country.

William Joyce had woken early that morning and although he ate no breakfast he drank a cup of tea. At one minute to nine, an hour later than initially planned, the Governor of Wandsworth Prison came to the condemned man’s cell to inform him that his time had come.

William Joyce had woken early that morning and although he ate no breakfast he drank a cup of tea. At one minute to nine, an hour later than initially planned, the Governor of Wandsworth Prison came to the condemned man’s cell to inform him that his time had come.

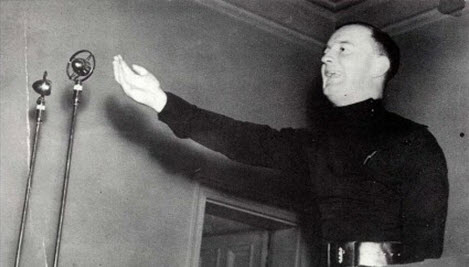

The walk to the adjacent execution chamber was but a few yards but there was just enough time for Joyce to look down at his badly trembling knees and smile. Albert Pierrepoint, the practiced and experienced hangman, said the last words that Joyce would ever hear: “I think we’d better have this on, you know,” before placing a hood over the condemned man’s head followed immediately by the noose of the hanging rope.

A few seconds later the executioner pulled a lever which automatically opened the trap door beneath Joyce’s feet. Almost instantaneously Joyce’s spinal cord was ripped apart between the second and third vertebrae, and the man known throughout the country as Lord Haw-Haw was dead.

At about the same time, as the hangman pulled his deadly lever, a group of smartly dressed men in winter coats stepped away from the main crowd outside the gates of the prison and behind some nearby bushes, almost surreptitiously, were seen to raise their right arms in the ‘Heil Hitler!’ salute.

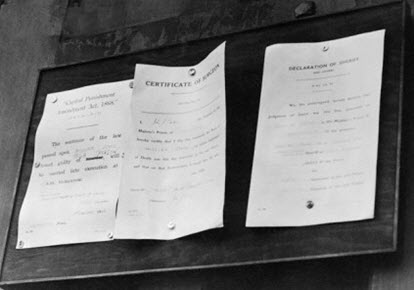

At eight minutes past nine, a prison officer came out and pinned an official announcement that the hanging of the traitor William Joyce had taken place.

At 1pm the BBC Home Service reported the execution and read out the last, unrepentant pronouncement from the dead man:

“In death, as in this life, I defy the Jews who caused this last war, and I defy the power of darkness which they represent. I warn the British people against the crushing imperialism of the Soviet Union. May Britain be great once again and in the hour of the greatest danger in the west may the Swastika be raised from the dust, crowned with the historic words ‘You have conquered nevertheless’. I am proud to die for my ideals, and I am sorry for the sons of Britain who have died without knowing why.”

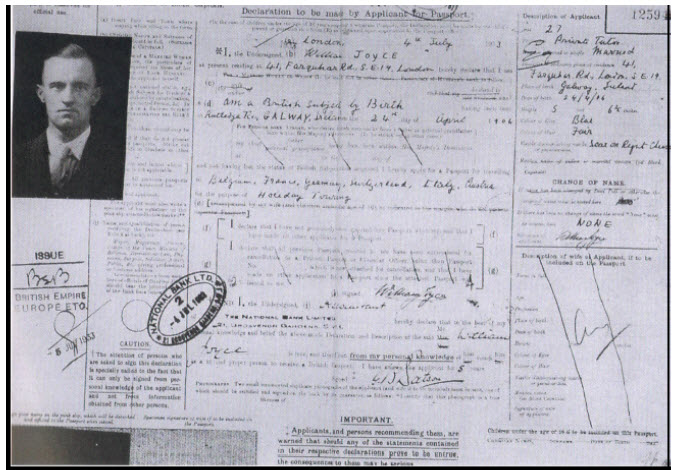

William Joyce had actually been born in Brooklyn, New York forty years previously to an English Protestant mother and an Irish Catholic father who had taken United States citizenship. A few years after the birth, the family returned to Galway where William attended the Jesuit St Ignatius College from 1915 to 1921. William had always been precociously politically aware but both he and his father, rather unusually for Irish Catholics at the time, were both Unionists and openly supported British rule.

In fact, Joyce later said that he had aided and ran with the infamous Black and Tans, the notoriously undisciplined and brutal British auxiliary force sent to Ireland after the First World War, in an attempt to help put down Irish nationalism. Joyce actually became the target of an IRA assassination attempt in 1921 when he was just sixteen.

For his own safety William immediately left for England, and after a short stint in the British army (he was discharged when it was found he had lied about his age) he enrolled at Birkbeck College of the University of London where he gained a first but also developed an initial interest in Fascism.

In 1924, while stewarding a Conservative Party meeting at the Lambeth Baths in Battersea, a seventeen year old Joyce was attacked by an unprovoked gang in an adjacent alley-way and received a vicious and deep cut from a razor that sliced across his right cheek from behind the earlobe all the way to the corner of his mouth. After two weeks in hospital, he was left with a terrible and disfiguring facial scar. Joyce was convinced that his attackers were ‘Jewish communists’ and the incident became a massive influence on the rest of his life.

In 1932 Joyce joined Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists and within a couple of years, he was promoted to the BUF’s director of propaganda and not long after appointed deputy leader. Joyce was a gifted speaker and for a while became the star of the British fascist movement. He was instrumental in moving the union towards overt anti-Semitism – something of which Mosley had always been relatively uncomfortable.

Joyce’s career with the British Union of Fascists only lasted five years when, with membership plummeting, a devastated Joyce was sacked from his paid position in the party by Mosley in 1937.

In late August 1939, shortly before war was declared and probably tipped off by a friend in MI5 that he was about to be arrested, Joyce and his wife Margaret fled to Germany. Joyce struggled to find employment until he met fellow former Mosleyite, Dorothy Eckersley, who got him recruited immediately for radio announcements and script writing at German radios’ English service in Berlin.

Crucially this was at a time when his British passport was still valid (although born in New York and brought up in Ireland Joyce had lied about his nationality to obtain a British passport – complications and niceties such as proving one’s identity with a birth certificate weren’t needed at the time) ostensibly to accompany Mosley abroad in 1935.

Dorothy Eckersley

Dorothy Eckersley

The infamous nickname of ‘Lord Haw Haw’, associated with William Joyce to this day, was coined by a Daily Express journalist called Jonah Barrington. It’s not widely known but the title was actually meant for someone else completely – almost certainly a man called Norman Baillie-Stewart who had been broadcasting in Germany from just before the war. The nickname referenced Baillie-Stewart’s exaggeratedly aristocratic way of speaking. Barrington had written:

A gent I’d like to meet is moaning periodically from Zeesen (the site in Germany of the English transmitter). He speaks English of the haw-haw, dammit-get-out-of-my-way variety, and his strong suit is gentlemanly indignation.

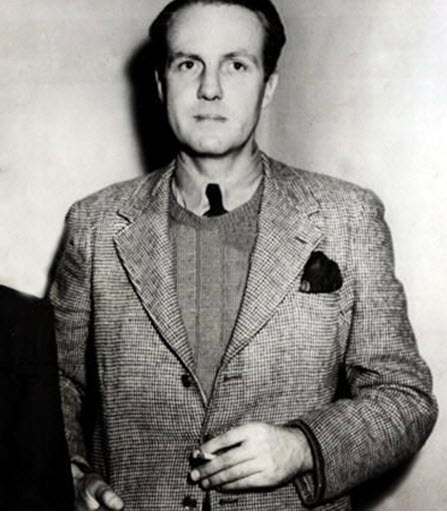

Norman Baillie-Stewart – the real Lord Haw Haw

Norman Baillie-Stewart – the real Lord Haw Haw

Baillie-Stewart had already been convicted as a traitor by the United Kingdom for selling military secrets to Germany in the early thirties. He had the dubious distinction of being the last person in a long line of infamous people to have been imprisoned in the Tower of London for treason.

Late in 1939 when William Joyce had become the more prominent of the Nazi propaganda broadcasters, although at the time no one knew who he was; Barrington swapped the title over to Joyce.

Listening to Lord Haw Haw’s broadcasts (which famously always began with the words “Germany Calling, Germany Calling”) was officially discouraged, although, incredibly, about 60% of the population tuned in after the BBC news every night. The BBCs output at the beginning of the war was said to have been exceedingly dreary and the British public seemed to prefer being shocked rather than bored.

Lord Haw Haw’s over-the-top and sneering attacks on the British establishment were really enjoyed, but in an era of state censorship and restricted information, there was also a desire by listeners to hear what the other side was saying. At the start of the war, simply because there was more to brag about, the German news reports were considered, by some people, to contain slightly more truth than those of the BBC.

As the tide turned in the latter stages of the war Joyce and his wife moved to Hamburg. On the 22nd April 1945 he wrote in his diary:

‘Has it all been worthwhile? I think not. National Socialism is a fine cause, but most of the Germans, not all, are bloody fools.’

Eight days later, and on the very day that Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide in their Berlin Bunker, Joyce made his last drunken broadcast – the remains of his Irish accent can be heard through his slurring voice.

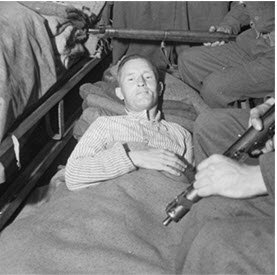

At the end of the war, William and his wife Margaret fled to a town called Flensburg near the German/Denmark border and it was there, in a nearby wood, that Joyce was captured by two soldiers. They, like Joyce, were out looking for firewood. Joyce stopped to say hello and one of the soldiers asked: “You wouldn’t by any chance be William Joyce, would you?” To ‘prove’ otherwise, Joyce reached for his false passport and one of the soldiers, thinking he was reaching for a gun, shot him through the buttocks, leaving four wounds.

The arrest was utter poetic justice. The soldier who had shot the infamous broadcaster was called Geoffrey Perry; however, he had been born into a German Jewish family as Horst Pinschewer and had only arrived in England to escape from Hitler’s persecutions. So, in the end, a German Jew, who had become English, had arrested an Irish/American who pretended to be English but had become German.

Back in London, he was charged at Bow Street Magistrates Court and in the dock he quietly stated: “I have heard the charge and take cognisance of it.” He was subsequently driven to Brixton Prison in a Black Maria and on arrival, he said: “So this is Brixton.” “Yes,” retorted his guard, “not Belsen.”

The trial of William Joyce began on 17 September 1945 and for a short period of time, when his American nationality came to light; it seemed that he might be acquitted. “How could anyone be convicted of betraying a country that wasn’t his own?” It was argued. However, the Attorney General, Sir Hartley Shawcross, successfully argued that Joyce’s possession of a British passport (even if he had misrepresented himself to get it) entitled him to diplomatic protection in Germany and, therefore, he owed allegiance to the King at the time he started working for the Germans.

It was on this contrived technicality that Joyce was convicted of treason on 19th September 1945. The penalty of which, of course, was death.

Sir Hartley Shawcross, later said that the trial of William Joyce was not one of which he was especially proud.

A sizeable minority of the population were uncomfortable with the verdict mainly because of the nationality issue but also because he was always seen as a bit of a joke-figure rather than someone trying to bring the country down. On Christmas day 1945 an accountant named Edgar Bray wrote to the King:

‘I know nothing about Joyce and nothing about his Politics. I don’t know much about Law either, but I do know enough to be firmly convinced that we are proposing to hang Joyce for the crime of pretending to be an Englishman which crime, so far as I am aware, in no possible case carries a capital penalty. It happens to be just our bad luck, that Joyce actually was an American, (and now is a German subject), but that is no reason to hang him because we are annoyed at our bad luck.’

The historian AJP Taylor made the point that Joyce was essentially hanged for making a false statement on a passport – the usual penalty for which was a paltry fine of just two pounds.

Interior of Wandsworth Prison

Interior of Wandsworth Prison

A cell in Wandsworth Prison in the late 1940s

A cell in Wandsworth Prison in the late 1940s

Albert Pierrepoint

Albert Pierrepoint

Not long after Albert Pierrepoints expert execution and with the blood from Joyce’s scar, that had burst open during the hanging, still dripping onto a spreading red stain on the canvas floor, the body was taken to the prison mortuary. A coroner pronounced that the death was due to “injury to the brain and spinal cord, consequent upon judicial hanging”.

There were specific rules pertaining to the burial of executed prisoners at the time, and William Joyce’s body was treated as any other. True to the normal rules he was buried within the Wandsworth Prison walls, in an unmarked grave, and was allowed no mourners. The body was dumped in the middle of the night, literally unceremoniously, on top of the remains of another man, a murderer called Robert Blaine who had been hanged five days previously.

In total 135 people were hanged at Wandsworth Prison during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the final execution taking place when Henryk Niemasz was hanged on 8 September 1961 the for murder of Mr. and Mrs. Buxton in Brixton.

Incidentally, the gallows at Wandsworth were not dismantled until 1993, 29 years after the last execution in this country and 24 years after the death penalty was abolished for murder, also, the death penalty still existed for treason until 1998.

The condemned cell is now used as a television room for prison officers.

Lord Haw Haw

Lord Haw Haw

NEW EVIDENCE CONFIRMS ‘LORD HAW HAW’ WAS A BRITISH SECRET SERVICE AGENT AND NOT A TRAITOR

In May 2011, an 82-year-old widow, Heather landolo, the daughter of William Joyce, the man perhaps better known as ‘Lord Haw-Haw’, made an application through her lawyer to the Criminal Cases Review Commission to have her father’s guilty verdict for high treason, for which he was executed on 3 January 1946, overturned. Mrs landolo was 17 when William Joyce was hanged at Wandsworth Prison.

The application asserted that not only was her father not technically British, having acquired German nationality, and, therefore, unable to be a traitor, but he was also a double agent for MI5 throughout the war, a protégé of the spymaster who inspired Ian Fleming to create the Bond character M.

Joyce’s conviction was controversial, owing to the serious doubts about his nationality. The execution was also seen as a harsh penalty for someone who, by the end of the war, was mocked by ordinary Britons as a figure of fun. Those who listened to Joyce’s earlier broadcasts described a ‘sneering, horrible voice… full of vindictive pleasure.’ The British authorities wanted him brought to justice.

Joyce was captured by British intelligence officers at the end of the war near Germany’s border with Denmark and brought back to London for trial and execution.

Mrs. landolo, a retired schoolteacher, believes her father was the victim of an injustice. “He was so loyal that every time he heard the national anthem, God Save the King, he stood up,” recalls Mrs. landolo. She misses her father terribly. “I don’t think he hated Britain at all. He was very pro-Empire.”

When Joyce landed at the airport having been brought back, he is claimed to have stated: ‘Britain, God bless her.’ “He was glad to be back on British soil again,” Mrs. Iandolo said. “I don’t have any proof that he was working for the British but I don’t think that he could have forgotten his pro-British sympathies. It is possible he was a double agent. He never mentioned it in his letters during the war but then it was the secret service, the silent service.”

Questions were raised by the initial submissions to the CCRC included: was Joyce tipped off that he would be arrested and, if so, why? Was he helping MI5 and Maxwell Knight during his time in the British fascist movement? How did British intelligence track him down so easily? Was he later double-crossed by MI5 and allowed to go to the gallows? But perhaps most intriguingly of all, the CCRC application raised the issue that Joyce was passing secret messages to British agents through his broadcasts.

Since the initial CCRC application, new evidence came to light. This evidence takes the form of the 1933 application made by William Joyce for a British passport which, according to the appeal transcripts was not able to be located. It appears beyond any doubt that the passport was issued with the knowledge of the Security Services as a protection for Joyce in the event such was required. That the passport was subsequently used for Joyce’s conviction and execution is lamentable as much as tragic.

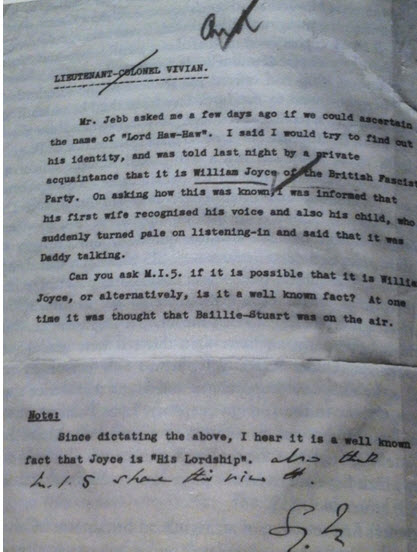

Another document emerged and found by lawyers acting for Mrs. Iandolo, a letter, dated 19 July 1941, sent from a Security Services Officer to William Joyce. The letter was intercepted by ‘Imperial Censorship’, Bermuda from a certain ‘Maurice’ of Norfolk, Virginia, addressed to ‘William Joyce in Berlin’. The letter states as follows:

‘Thank you very much indeed for the remarkable photographs showing widespread damage of several sections of Berlin as a result of RAF bombing. They are far superior to some similar snapshots which I received from Ed Delaney many months ago. It is perhaps indiscreet to ask, but how in the world did you manage to get them past the censors? Your last letter was rather unusual in one respect: we feel that you are losing interest in your job in Germany, and Martha is quite positive that you plan to leave there should you have the opportunity to do so. But for Heaven’s sake man, where could you go? Martha is a genius at reading between the lines and, strangely enough, the information which she gleans there from invariably turns out to be true, as you very well know. I am toying with the idea of joining up with the British in whatever capacity they will have me. Send more interesting pictures.’

Ed Delaney was, in fact, Edward Leopold Delaney, a US citizen who, like Joyce, was broadcasting German propaganda to America from Berlin. Delaney became active in ultra-right-wing/Coughlinite politics, and it was through affiliations cultivated in these movements that he was recruited in 1939 by the Reichsrundfunk Overseas Service to present a series of pro-German-from-an-American-perspective broadcasts.

Delaney claimed never to have formally espoused Nazi doctrine and constant friction with his supervisors at the RRG led to his departure from Berlin in 1943. He drifted around occupied Europe for two years and was finally arrested by Allied forces in Prague in May 1945. Investigators finally concluded that he was ‘too small a fry’ to bother with, and turned him loose in 1947.

Delaney was working for US Intelligence and after release in 1947 he spent a number of years touring the US as an ultraconservative lecturer, and finally settled down in Southern California, where he spent the rest of his life as a small-town newspaper columnist. He was mysteriously killed in a pedestrian accident in 1972 at the age of 86, shortly after he had stated he would ‘tell the truth about Joyce et al during the war’. Was he murdered?

There is evidence that the Foreign Office at the time was well aware that Joyce was working undercover, but, that they became aware of such only after receipt of this intercepted letter. The operation involving Joyce was so sensitive and secret that only a handful of people knew about it.

On 6 March 1944, the Attorney General of the day, Sir Donald Somerville’s, was sought to provide a formal advice as to whether or not William Joyce had committed treason. Documentary evidence of his reply found in the covert files kept at the Security Services by lawyers acting for Joyce’s daughter state:

‘I am of the opinion that the act of broadcasting is not an offence under section 1 of the Treason Act. I am satisfied that reading out a broadcast in an act, but am of the opinion that the words here used, although, of course, they might affect morale, are not likely to give assistance to the naval, military or air operations of the enemy.’

That document was never made available at William Joyce’s trial.

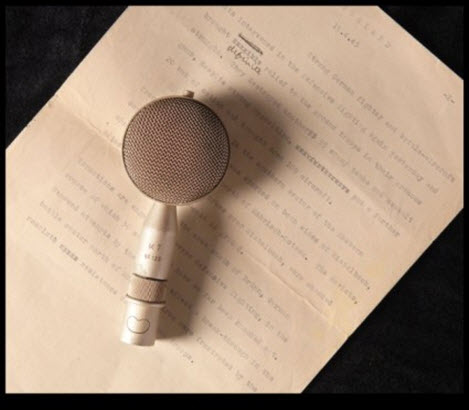

William Joyce was covertly in his broadcasts passing vital information to the British Military Intelligence. Joyce had for some weeks, in 1944, in his broadcasts been hinting at a ‘secret weapon’ that Germany had developed and would use. This was the V-1. When it was launched the British Military had no idea what it was but Joyce told them in his satirical manner fooling the Germans decidedly. This is a transcript of his broadcast:

“London and Southern England have now been under bombardment for more than a week. For nine days, with very little interruption, the V-1 projectiles have been descending on the British capital. May I remind you the name V-1 has been given to them officially. ‘V’ is the capital letter of the German word ‘Vergeltung’, which means ‘retaliation’, and its use to denote the concept of victory must be familiar to nearly all of my listeners. The very term V-1 implies, of course, that Germany has other new weapons which have not as yet been employed against the enemy. That is a fact and is a fact, which even the British government is beginning to realise. The emergence of V-1 has provided a surprise for Germany’s enemies and I believe that they will have several other surprises ‘before the autumn leaves fall’, if I may borrow a phrase which Mr. Churchill used on a certain occasion.”

The mention of the name ‘Mr. Churchill’ meant the message was for the British wartime leader and, of course, William Joyce was telling the British Government that ‘other weapons’ referred to the atom bomb. This information Joyce had successfully relayed to London. The fact that Joyce had made this information public confirmed to Sir Winston Churchill that D-Day, namely the attack on Germany had to be hurried as there was no time to lose.

Had Joyce not made that broadcast, and had Joyce not relayed to the British Government the information, regarding the atom bomb then the Second World War may well have taken a diverse course.

Since 1941, MI5 had been monitoring the Joyce broadcasts for diverse reasons. They contained, of course, messages for the government. The official reason was to keep monitoring Joyce who was ‘officially’ deemed a traitor. Some of William Joyce’s broadcasts MI5 had transcribed with the help of the BBC. However, from 1941 all his broadcasts had to be transcribed in order, that after the war, and upon capture, Joyce could be tried and admissible evidence available. That was the formal version. MI5 was well aware that during the war there were, within its ranks, infiltrated double agents reporting to Berlin.

Those at MI5 that were not aware of the true position of William Joyce wanted to ensure he would hang after the war. Since 1941 however, there had been some concerns that the wording of the ‘Treason Act’ really could not be stretched to include William Joyce’s circumstances.

Lawyers found at MI5 within the covert Joyce file a memorandum from Edward Hale Tindal Atkinson the then Director of Public Prosecution stating:

“The words of the Act are somewhat limited. I find it difficult to apply them to the kind of propaganda put out by Joyce.”

After the war, Tindal-Atkinson helped prepare all the so called ‘spy cases’ but retired mysteriously in 1944, because, according to secret papers, ‘could not live with his conscience’ and became the Treasurer of Middle Temple. In the middle of the 1950s, he had made public the fact he would write his memoirs and experiences and specifically the case of William Joyce. In strange and as yet wholly unexplained circumstances, and before he could write a word, he died following an accident at his home on 26 December 1957. Was he murdered?

In 1941-1944, Special Branch and MI5 had orders to ‘record solemnly examples of Haw-Haw broadcasts’ which at that time cost some £5 per broadcast. When a recording was completed at the BBC the Officers would go to a private room where the recording was played back and the Special Branch Officer or MI5 Agent would transcribe them in his notebook. What was so special about those notebooks and why they were retained? Why was everyone who was present required to sign the notebooks with a ‘sharp instrument’ on a central part of the record? The records, after signature, were dated, placed in cardboard containers and fastened together with tape. The tape was sealed by an MI5 Officer called T.M. Shelford, who impressed his signet ring on sealing wax.

T.M. Shelford was an MI5 agent but also a Solicitor – one of many recruited by MI5.

All these factors would have been of vital importance, of course, to the court, but access to them simply was denied.

On 11 December 1945, the day after William Joyce’s appeal to the House of Lords had commenced, the then Home Secretary, Chuter Ede, called an emergency meeting at the Home Office. That meeting was documented but the minutes were coveted and made subject to a hundred year rule on disclosure. The document remains within a covert file kept at the Home Office with the label ‘William Joyce’ and discovered by lawyers acting for Heather Iandolo.

It contained a minute of two meetings called upon by the Home Secretary and certainly should have been disclosed at Joyce’s trial, or, at least, the decision contained within such as it would have had an impounding effect upon the trial. The minute of that meeting stated:

“At the meeting on 18th September (1945), the Cabinet decided that should William Joyce be found not guilty by the Court of Trial, he should be interned as an undesirable enemy alien and held in custody until the position should be reached on his disposal. I decided to make a deportation order against him with a view to his deportation to Germany, of which country he is a national. In case his appeal succeeded, the deportation order is still in force and, in the event of the House of Lords deciding that Joyce is not guilty, I propose that the deportation order should be enforced and that Joyce should be immediately detained pending his removal to Germany.”

The Trial Judge, The Court of Appeal and the House of Lords were entitled, and should have seen the note, and should have been made aware that Joyce was subject to deportation and the reasons contained within such order.

Finally – also contained in the covert file found by the lawyers a note from Stalin to the British Ambassador in Moscow, severely criticising the trial of William Joyce. Contained within that file was also a memo from an MI5 Officer dated 10 December 1945:

“We are worried about what the Russian reaction might be if the Lords quash his conviction.”

The evidence, not made available to both the Court of Appeal and the House of Lords in the form of the intercepted letter and other material, make for compelling evidence that the conviction of William Joyce was indeed ill-founded.

In essence, Joyce was no traitor, he was working for British Intelligence, and he trusted that the authorities would not let him down at his hour of need and that his execution would be prevented at the last minute by his compatriots. As such, Joyce could not have committed an act of treason. Sadly the system failed him and a gross injustice stands to be corrected.

Mrs. Iandolo is keen for the appeal to succeed. “It would be a bit late in the day but it would be a record of history,” she says. “There should be nothing to prevent the investigation and the opening of the intelligence files. We pride ourselves on liberty in this country. There was another side to my father that needs to be revealed.”

Below is but one covert document on the basis of which one can draw their own conclusions.

Giovanni Di Stefano

This article was originally published December 2012.

NB: Some images retrieved from Google, will remove at owner’s request.

As Joyce was a German citizen his trial should have been held in Germany.

I notice the article titled “Adolf Hitler, the British Security Services Connection and an Unmarked Grave in Spain” by Giovanni Di Stefano has vanished from this site and also from archive.org 🤔

Well, LORD HAW HAW more than precisely GOT WHAT WAS COMING TO HIM!!! Being a PROPAGANDIST-A CIVILIAN SPY-A RAT; the EXECUTION, IS more than precisely EXACTLY WHAT WINGNUT WILLY JOYCE-Lord Haw Haw DESRVED; DISHONOUR BEFORE DEATH!!!

Brian Murza…Killick Vison, W.W.II Naval Researcher-Published Author, Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada.